Frustrated residents of a Denver suburb say state law is forcing them to participate in a major oil and gas drilling project against their wishes, so they launched legal challenges with potentially significant consequences for the industry.

Backed by a federal judge, they have a chance this week to ask state regulators to block multiple wells planned within about 1,300 feet of homes in the city of Broomfield.

The dispute is a microcosm of a broader battle in Colorado, where burgeoning subdivisions overlap with rich oil and gas fields, bringing drilling rigs and homes uncomfortably close.

The battle is playing out on multiple fronts. Broomfield residents are taking their case both to state regulators and federal court. In the Legislature, majority Democrats are pushing legislation that would give the Broomfield residents and others like them powerful new weapons to keep drilling rigs away from their homes.

In Broomfield, about 20 miles north of downtown Denver, Extraction Oil and Gas wants to drill in open areas amid the Wildgrass neighborhood of roomy new homes.

A group called the Wildgrass Oil and Gas Committee says the wells are dangerously close to their homes, although they would be beyond the 500-foot setback required by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, which regulates the industry.

They also argue that state laws is forcing residents who own the mineral rights under their property to lease or sell them to Extraction through a process called forced pooling. It allows the oil and gas commissioners to require all the owners of nearby minerals to sell or lease them to an energy company in exchange for a share of the profits.

Created a century ago, forced pooling was designed to prevent the proliferation of oil derricks. Landowners were scrambling to drill their own wells to keep a neighbor’s well from grabbing their oil. Forced pooling allowed a single well to gather the oil, and the income was distributed among the owners.

In Broomfield, some mineral owners are resisting.

“We did not have any interest in going into business with an oil and gas company,” said Lizzie Lario, a member of the Wildgrass group, who along with her husband owns the mineral rights under their home that would be included in the project. She said she did not want to participate in something that could result in spills, fires and explosions so close to homes.

Many states have forced pooling laws, though some require a certain percentage of owners to consent before a pooled well can proceed. Colorado allows forced pooling with the approval of a single party, provided they have the means to get the minerals out.

The Wildgrass committee said the oil and gas commission repeatedly delayed a hearing on their objections, so they filed suit, asking a federal judge to rule the forced pooling law unconstitutional.

The judge hasn’t ruled on the lawsuit, but he ordered the commission to hold the long-delayed hearing. It’s expected to take place Tuesday.

Kate Merlin, the Wildgrass committee’s attorney, said residents want the commission to deny the forced pooling application on the grounds that Extraction has not shown it’s capable of developing the project in a way that’s economically sustainable and that protects public safety.

Extraction spokesman Brian Cain said the company met with Broomfield officials and a citizens task force more than 28 times over two years and adopted 95 percent of the task force’s recommendations. The buffer zone around the well site is four times the state requirement, he said,

He called Extraction’s operating agreement with Broomfield “the gold standard in Colorado.”

Forced pooling is critical to the oil and gas industry in Colorado, said Scott Prestidge, a spokesman for the Colorado Oil and Gas Association. Without it, some wells would not be financially viable.

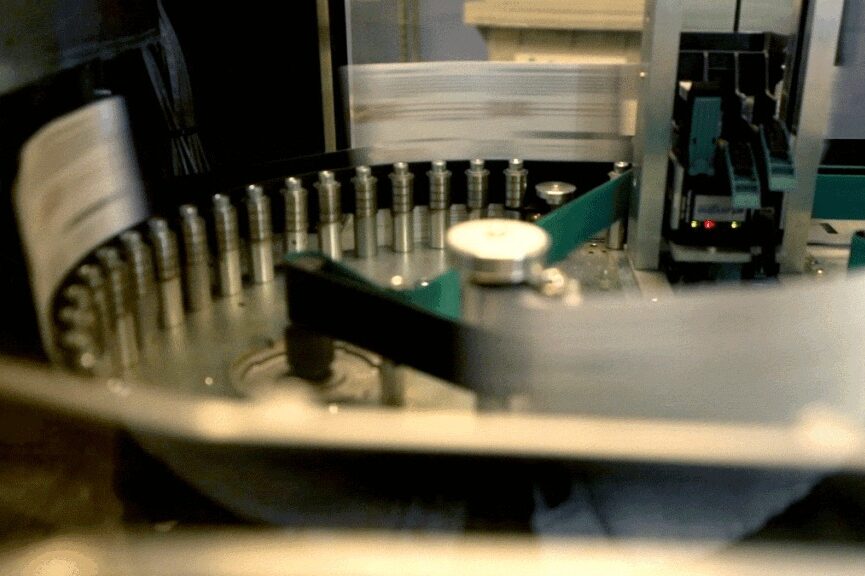

Forced pooling combined with horizontal drilling — well bores that penetrate straight down, then bend outward laterally for thousands of feet — make it economical to drill in the oil field north of Denver, he said.

A single site with horizontal wells extending two miles can replace as many as 18 vertical wells, he said. That makes it cheaper to operate and control pollution, and it reduces the amount of land and roads required.

Prestidge declined to comment on the forced pooling lawsuit or the specifics of the oil and gas bill making its way through the Legislature. Among other changes, the bill would require the consent of at least 50 percent of the mineral owners affected before forced pooling could proceed.

Democratic lawmakers said they consulted with oil and gas companies on the bill, but Prestidge said they never got to review the language or fully grasp the intent before it was introduced.

“Right now there are significant concerns with the piece of legislation that is being rushed through the process and has several elements within it that could use some constructive conversation,” he said.