It’s a typical December Saturday night in Aspen, Colorado. Crowds festooned in designer coats and cowboy hats tip-toe over icy sidewalks and past chic bars pumping out music. Mannequins peer from the glowing windows of Gucci and Ralph Lauren.

Ryan O’Leary, co-owner of Real Aspen, across the street from the Prada, will tell you that wealth is commonplace here. In the same breath he’ll point out his store has a full Russian sable coat that retails for $60,000.

“In Aspen, there’s always the opportunity that you could be talking to a billionaire and you would never know it,” he said.

It wasn’t always this way.

Steve Fling of Castle Rock remembers stories of a different Aspen. He grew up in Pennsylvania, and his best friend’s mom was from the now-posh resort town. After each vacation back to Aspen, the family would return with photos and laments of an influx of privileged people “changing, the small-town feel of their hometown,” he said.

When did Aspen “become a Mecca or a destination for the rich and famous?” That’s the question Fling asked Colorado Wonders to get to the bottom of.

Several generations back, Aspen sat fallow. Historian Mike Monroney paints a picture of a remote outpost where a few hearty souls somehow scraped by (and grew their own food) at nearly 8,000 feet.

“Sometimes you moved into the Hotel Jerome during the winter because you couldn’t afford to heat your house,” he said.

The Jerome was founded in 1889 alongside the landmark Wheeler Opera House and has come a long way as “shelter.” The fanciest rooms there now go for thousands of dollars a night. Aspen boomed in the late 1800s as a silver mining hub, then busted, hard, when the mining economy collapsed and disappeared. Out of the downturn, the environment slowly healed, the air cleared and rivers became drinkable once more.

Aspen was again pristine, yet offered people very few ways to make a living. Monroney said “the population dwindled to 700 by 1930. We call those years ‘The Quiet Years.’”

Into this silence walked a man with a vision for what is now “the Aspen idea,” Monroney said: “Mind, body, spirit.”

Walter Paepcke, a businessman from the East Coast, wanted his legacy to be more than the cardboard boxes his company made. Aspen in the 1940s, Monroney said, was still bottomed out, full of decaying Victorians and empty streets. Skiing had arrived a few years before, but World War II stalled any big development. Paepcke didn’t ski, but when he looked out on steep, snowy slopes cradling a ghost of a town, Monroney said he saw a business opportunity.

Paepcke connected with Friedl Pfeifer, a former soldier who had trained in the area with the storied 10th Mountain Division, and world-famous designer Herbert Bayer. Together, they set into motion a lofty vision: creating a magnet for great minds.

Monroney said the desire was for Aspen to be a place where exemplary artists, scientists and economists “could all come together and share ideas, and each with their own unique perspective, come up with solutions to the great issues of humanity.”

That’s still the heart of The Aspen Institute, the think-tank Paepcke helped start in 1949. He also founded the Aspen Music Festival, and to support it all, the Aspen Skiing Company.

All three grew together, giving Aspen a foundation that Monroney thinks still fuels the town today. Mind, body, spirit, all in a place that had been isolated for so long that Monroney said locals didn’t care who you were. That was even true for Gary Cooper, one of the town’s first Hollywood visitors.

“Celebrities could come here and rub shoulders and be almost anonymous, and I think enjoyed that — and have over the years,” Monroney said.

Ask just about any longtime local and you’re bound to hear a story about sitting next to Jack Nicholson at the bar or seeing Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell stroll down the street, with locals passing by without a care.

“It’s different now,” Monroney said — especially if you’re someone like Mariah Carey.

A 2018 video circulating online shows paparazzi hounding the singer as she enters a fancy Aspen store with her bodyguard. An older woman in a plain puffy jacket hustles past like she wants no part of the scene. Which begs the question, how have Aspen’s changes affected the everyday people who live here?

Pitkin County Sheriff Joe Di Salvo has a joke about it.

“You know, how many Aspenites does it take to change a lightbulb?” he said. “And the answer is usually 100. It’s one to actually change the lightbulb, and 99 to remember how great the old lightbulb was.”

With a laugh, Di Salvo admitted he’s one of the nostalgic ones. Though he still loves this place, he misses the low-key vibe he felt when he first rolled into town in 1980, before Aspen became shorthand for extreme wealth.

Sure, he’d see some famous people time and again, but back then “celebrities were more interested in being locals than it was us being attracted to their celebrity,” he said. In fact, it seemed as though celebs were jealous of his lifestyle. He joked they came to town not to be noticed, but to feel “poor and local.”

The transition seems to have taken place sometime between the mid-’80s and early-’90s. The 1986 opening of the Silver Queen Gondola or the swanky St. Regis Hotel may have hastened the metamorphosis.

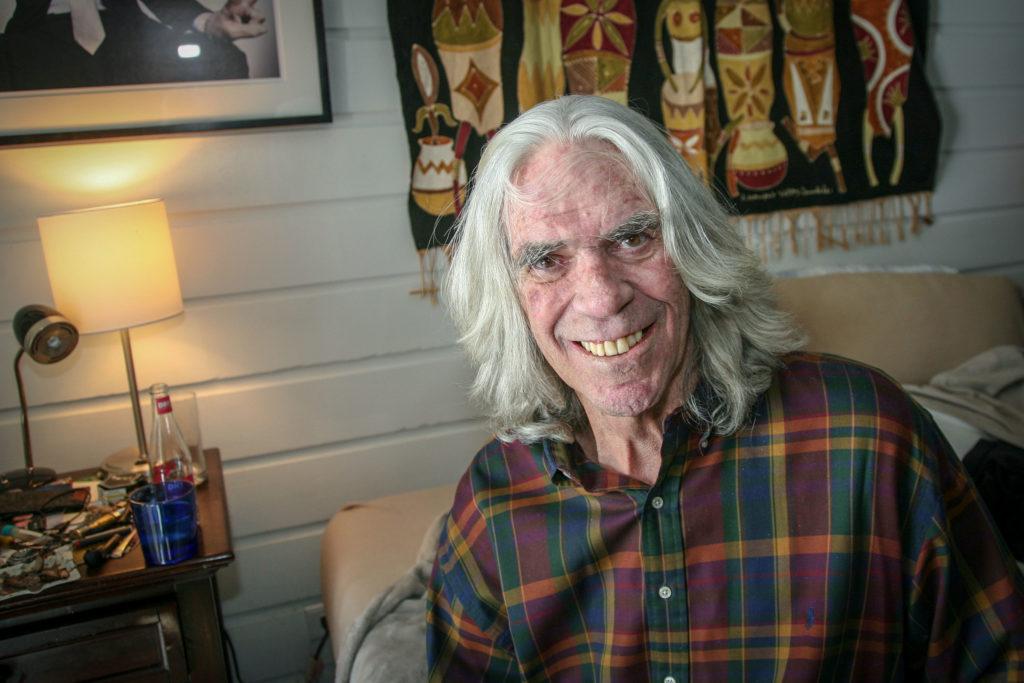

Bob Braudis, Di Salvo’s predecessor, watched the shift during his 24 years as an iconic, counter-culture sheriff. His job was a balancing act between the needs of everyday people and famous folks, and of course, the super-rich.

The far end of the Roaring Fork Valley can only hold so many. And as more of the rich and famous “bought homes here, more and more of them joined,” he said. Which meant a lot less of everyone else. In fact, Paula Zurcher, the 90-year-old daughter of Walter Paepcke, just put her mountain mansion outside of town up for sale. The asking price? Only $18 million.

“The cost of housing here went from fairly expensive to unreachable for the working person,” Braudis said.

The only reason he’s here now is that he snagged one of Aspen’s coveted affordable housing units, a small studio apartment in a former motel by the airport. His cardiologist doesn’t think he should even live at this elevation, so he’s tethered to an oxygen tank in order to stay here.

He said does it “because of my homies.”

Braudis made a lot of friends over the last 50-something years. He affectionately calls many of them “freaks,” like his late buddy Hunter S. Thompson. He’s palled around with rabble rousers and visionaries, the types who fought to preserve the old houses and the surrounding wilderness. Locals like him believe the town is worth all the financial sacrifices it takes to be here.

“I realized I came here for the skiing, but I stayed here because of the magic of the people,” the former sheriff said.

So what about the Aspen forefather Walter Paepcke, and that mind-body-spirit idea he envisioned all those years ago? For many Aspenites it lives on in the art and music festivals, in the dignitaries who meet here, in the killer skiing. There’s also all those fur coats and Prada bags, and giant mansions that snake up the mountainsides. All of it is Aspen today.

Are you curious about something in the Centennial State? Ask us a question via Colorado Wonders and we’ll try to find the answer.