In Denver’s Cory-Merrill neighborhood, a wooden frame house stands out amongst its brick neighbors. Colleen Feely’s realtor told her the home was moved to the University and Interstate 25 neighborhood from somewhere near downtown in the 1920s.

“We are a little bit different,” she mused on a spring sunny morning.

That got her wondering: Did Denver ever ban wooden homes at some point, giving birth to the thousands of brick homes that line Mile High City streets today — perhaps even leading to her home being moved? If so, why?

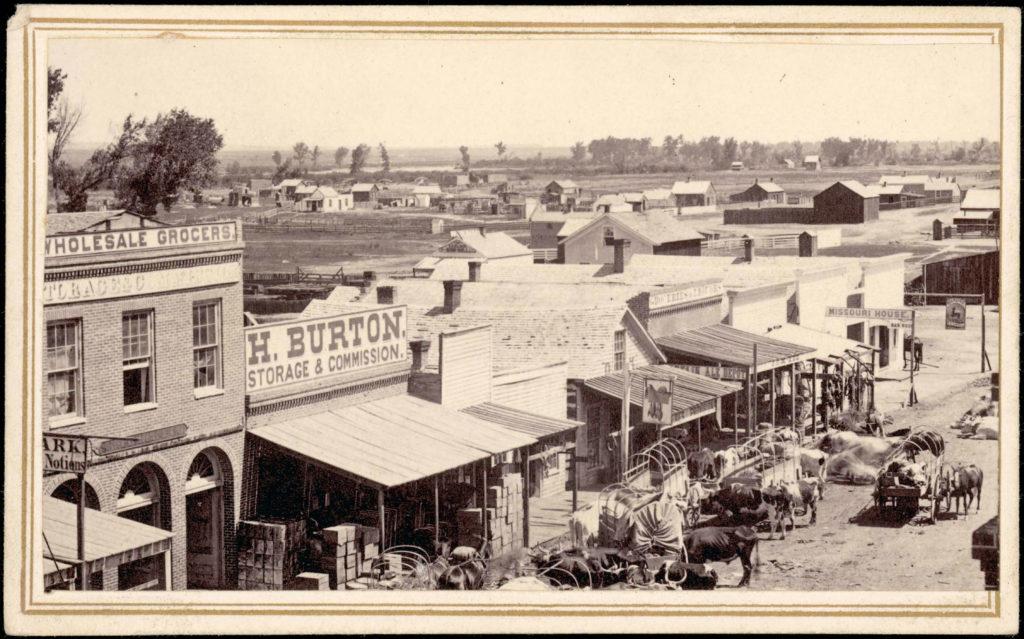

The answer — to the first question anyway — goes back to an April night in 1863. Denver was little more than a smattering of canvas and wood buildings near the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. A fire broke out at about 1:00 a.m.

By the next morning, most of the city was leveled.

“It would have looked pretty shocking,” said Alison Salutz, director of community programs at Historic Denver. “The buildings would have been kind of smokey hulls.”

The wooden buildings’ close proximity to each other made it easy for flames to spread, Salutz said. And some of the warehouses held highly flammable materials like flour and bacon.

“Imagine the next morning has kind of weird smell of burning bacon in the air,” she said.

The buildings that fared best were built out of brick. So the next day, April 20, 1863, city leaders approved a new ordinance that required, with few exceptions, all new buildings be made of fireproof materials like stone, brick or very heavy wood timbers.

Given Denver’s easy access to clay, brick quickly became the most common building material. The ordinance stayed on the books until some time around 1960, according to Katie Rudolph, an archivist and librarian at the Denver Public Library. The effects are still clear: As of 2017, nearly half of all homes in the city were made of brick.

Brick is a sturdy material. But given the age of many of Denver’s brick homes, some are due for major work. Gary Holt of Olde English Masonry, a mason who specializes in turn-of-the-century brick homes was recently called in for an emergency repair on a brick apartment building near City Park.

“The residents reported a loud bang,” Holt said. “They thought a bomb had gone off.”

Instead, a section of the wall had fallen out in the middle of the night. Because brick is relatively low maintenance, Holt said many homeowners don’t pay much attention until something extreme happens.

To fix aging buildings, Holt finds materials from the same era from scrap vendors like Mendoza Used Brick in Westminster. He even thinks about the people that laid them in the first place.

“You have to kind of get into their heads,” he said. “You put yourself back in there and OK, how would they fix this? How was this done?”

Holt said he’s glad to be helping preserve Denver’s brick legacy and wants residents to not take the city’s brick heritage for granted.

“Let’s keep brick around,” he said. “Let’s train people to take care of these buildings. Otherwise we’re going to lose them.”

So what about Feely’s other questions? Where did her wood house come from? And when was it actually built? Unfortunately, there really isn’t much of a paper trail to check. For her part, Feely is content to live with those mysteries.

“I love the house and the location is perfect,” she said. “I’m pretty happy here.”

Feely’s done a lot of improvements to the place over the years. Even though she may not know its full past, she’s doing her part to make sure it’ll still be standing for years to come — alongside all of its brick neighbors.