A decade ago, Danny Katz was all about trains. He still has a t-shirt that bears a message of support for the Regional Transportation District’s FasTracks program, a 2004 ballot measure that raised sales taxes to build out more than a hundred miles of passenger rail in the Denver metro.

“We were absolutely cheerleaders leading the drive to pass FasTracks,” said Katz, now the state director of the Colorado Public Interest Research Group. “And years after it was passed, I was one of the leaders saying, keep FasTracks on track.”

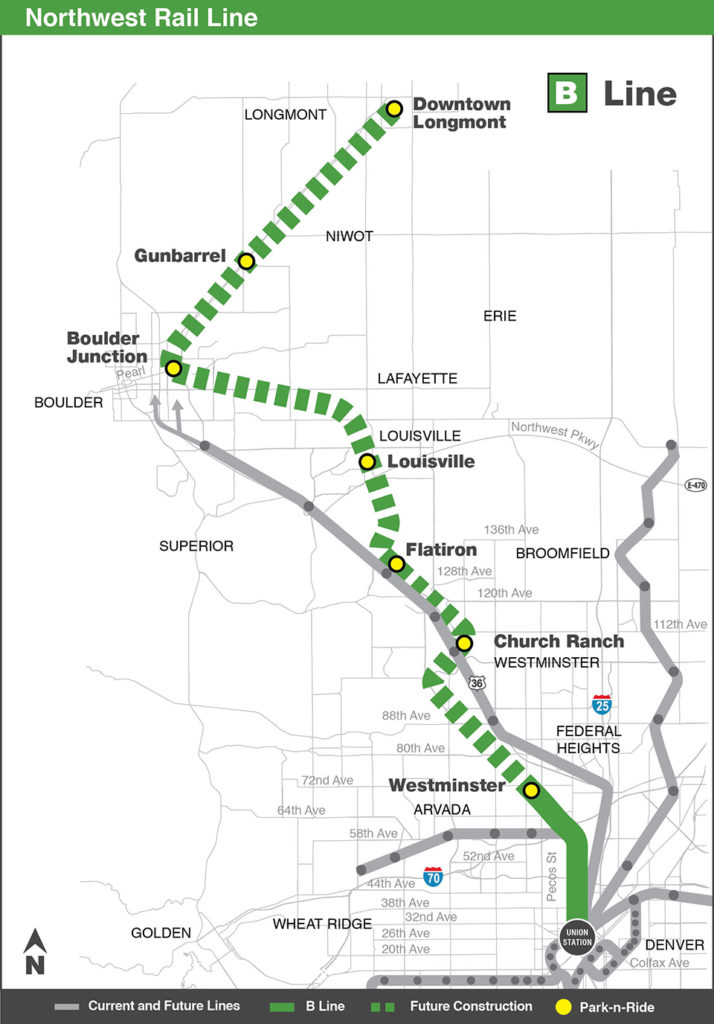

But Katz feels differently today, saying RTD should rethink a key part of FasTracks: a 41-mile rail line from Denver to Boulder and Longmont. That project is decades behind schedule and its estimated cost has nearly doubled to $1.5 billion. Some of its once-ardent backers, like Katz, have begun to turn against it. That's placed them in strange new alliances with political conservatives, and against local political leaders in the Boulder area.

FasTracks projects hit major delays during the Great Recession: Sales tax revenues plummeted, and costs rose, especially for construction materials and right-of-way. Still, through financial maneuvers like public-private partnerships and cost-cutting, RTD officials say about 70 percent of FasTracks is either finished or under construction.

But Katz said that doesn’t necessarily mean finishing the project is the wisest decision.

“Sometimes you’ve got to stop and say, ‘Wait a minute, we're about to spend $1.5 billion on one line. Is there a better way to use this money?’” he said.

Katz’ shift means he now agrees, on this one point at least, with the group that fought the hardest against FasTracks in the first place: The Independence Institute. That fact didn’t impress Jon Caldara, president of the libertarian policy think-tank.

“It makes me wish that they said so when the tax increases were being proposed,” Caldara said.

Katz and Caldara still have major philosophical differences. For example, Katz supports investing in infrastructure that promotes transit, walking and biking, while Caldara would rather the state give vouchers to transit-dependent residents and widen highways.

But both say that existing transit dollars should be spent in the most efficient way possible. Katz said RTD should develop more express bus lines, like the existing one between Denver and Boulder.

“The Flatiron Flyer is just a great example of great transit,” he said. “It's moving a lot of people along that corridor.”

(Regional Transportation District)

RTD now estimates the Boulder-Longmont train would carry only about 4,100 people a day during the week, a big drop from initial pre-Great Recession projections. The Flatiron Flyer, which RTD launched in 2016 at a cost of $190 million, carried an average of 11,600 people every weekday in 2018.

The efficiency of bus rapid transit-style lines means they should be a huge part of transit’s future in the Denver area, said Travis Madsen, transportation director at the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project. He said the RTD board’s recently re-stated goal of finishing FasTracks shouldn’t be their highest priority.

“We have an opportunity to get a lot more folks riding the transit system, getting cars off the road, reducing air pollution and generally making quality of life in our region better by focusing our investments on the projects that are going to give us the biggest bang for the buck,” he said.

The Flatiron Flyer buses use a toll lane on US 36 that’s also open to private shuttles and van pools. Caldara said it’s beneficial to transit users and those who are willing to pay a premium to get to their destination more quickly.

“When you build choo choo tracks, it means only RTD can use them,” Caldara said. “When you build a bus lane, it means everyone can be part of the solution.”

RTD is pursuing other bus rapid transit-style routes, including one from Boulder to Longmont. But the Flatiron Flyer isn’t technically bus rapid transit because it isn’t set up to operate in the fastest way possible. The speed difference is clear to commuters like Brian Paul Schroder, who takes the Flatiron Flyer from Denver to Louisville.

“The other day, we were stuck in a lot of traffic and we had to just fight over to the shoulder lane,” he said, standing at a bus stop on the edge of downtown Denver in June. “With all the merging traffic and everything, it was just a 20-minute additional delay.”

A train with its own right of way could skip right by the congestion, Schroder said. The RTD board of directors is exploring a limited service train that could open sooner (check this RTD staff presentation for a variety of scenarios under consideration), but the agency now estimates a full-service line won’t open until 2050 — unless new revenue is generated.

That could come from another sales tax increase, potentially a tough sell to voters who’ve already paid taxes towards a train that hasn’t been built. Schroder said he’d need to be sure RTD could uphold its promises, before he’d support another increase.

“It better run timely, and it better run often, and it better open on time,” he said.

RTD board director Judy Lubow, who represents Longmont, acknowledged the agency doesn’t have a great track record of delivering projects on time. She often hears about the lack of a train from frustrated constituents and elected officials in the northwest metro area. That’s a big reason why she supports finishing the line, even if it is expensive.

“Voters are still paying taxes for it. And government has no right, in my opinion, when it makes a promise, not to fulfill that obligation,” she said. “It's very destructive to democracy.”

The RTD board of directors is set to discuss the matter further at a public meeting on July 9.