The crack that has halted travel in the eastbound lanes of U.S. 36 near Westminster was likely caused by water under the roadway, officials said.

“It appears water has gotten underneath the section that’s collapsing,” Colorado of Department of Transportation spokesperson Tamara Rollison said. “It looks like it’s unraveling.”

A later press release stated: “Large cracks have developed into a sinkhole, with significant damage to the retaining wall under the road.”

Tricky soil could have contributed as well, an issue state transportation officials have long been aware could have potentially devastating effects.

Cristina Torres-Machi, an assistant professor of construction engineering management at CU Boulder said it looks like a nearly textbook example of what she called “slope failure,” essentially a landslide, one she would share with future classes on the matter. She said it’s likely because of collapsing soils.

As early as 2009, engineers warned of the potential pitfalls of the ground the highway passes over.

“Collapsing soils occur along the U.S. 36 corridor,” stated the final Environmental Impact Statement. “Upon inundation with water, these deposits undergo sudden changes in structural configuration with an accompanying decrease in volume that is expressed as settlement at the surface.”

According to the Colorado Geological Survey’s website, collapsible soils are a common problem throughout the state. The hazard was first recognized in western Colorado as far back as the 1890s, “when previously untouched land was first irrigated.”

In collapsible soil, the grains are “not packed tightly together. Instead, the grains are precariously stacked, like a house of cards,” the report states. “While strong in a dry state ... the introduction of water into these dry soils causes the ... binding agents to quickly break, soften, disperse, or dissolve.”

The U.S. 36 environmental impact statement recommended a variety of measures to deal with the soil, like “deep foundation systems” or “[f]oundation pads could also be designed to form a raft across any swelling or collapsing materials.”

CDOT did not immediately respond to questions about what engineering measures were employed along this section of U.S. 36.

The partnerships used to construct and expand the highway mean responsibility isn't immediately clear. Costs aren't, either.

Ames Construction, which joined with Granite Construction to design and build the expansion of U.S. 36, did not immediately return a request for comment. Plenary Roads Denver, through a public-private partnership, manages U.S. 36 and helped finance the second phase of the project. Plenary was not involved in the design and construction of the collapsed section of roadway.

Taxpayers could be on the hook for costs related to the collapse, according to a 2014 agreement between the Colorado Department of Transportation and Plenary, which collects toll dollars.

According to the 2014 version of the contract, which is subject to updates, while the damaged portion of highway was not Plenary’s job, if toll collection is suspended for more than 12 hours a year under certain emergency circumstances, the state could have to compensate Plenary, according to the contract.

A review of monthly operations and maintenance reports from Plenary through May didn’t indicate any advance warnings about problems with this section of road. (Ferrovial Services performs operations and maintenance on U.S. 36 for Plenary. Another division of Ferrovial, a Spanish company, is part of a joint venture rebuilding the interior of DIA, beset by potentially massive cost overruns and delays).

A spokesman for Plenary said a crack in the road that formed last week was the first indication that something was wrong.

Rollison, with CDOT, said they aren’t ready to assign blame.

“Right now our focus is on getting this fixed,” Rollinson said. CDOT will take the lead on contracting for any major repairs.

Crews must now rebuild the roadway — it’s not a patchwork job, and yes, traffic will be worse in the meantime.

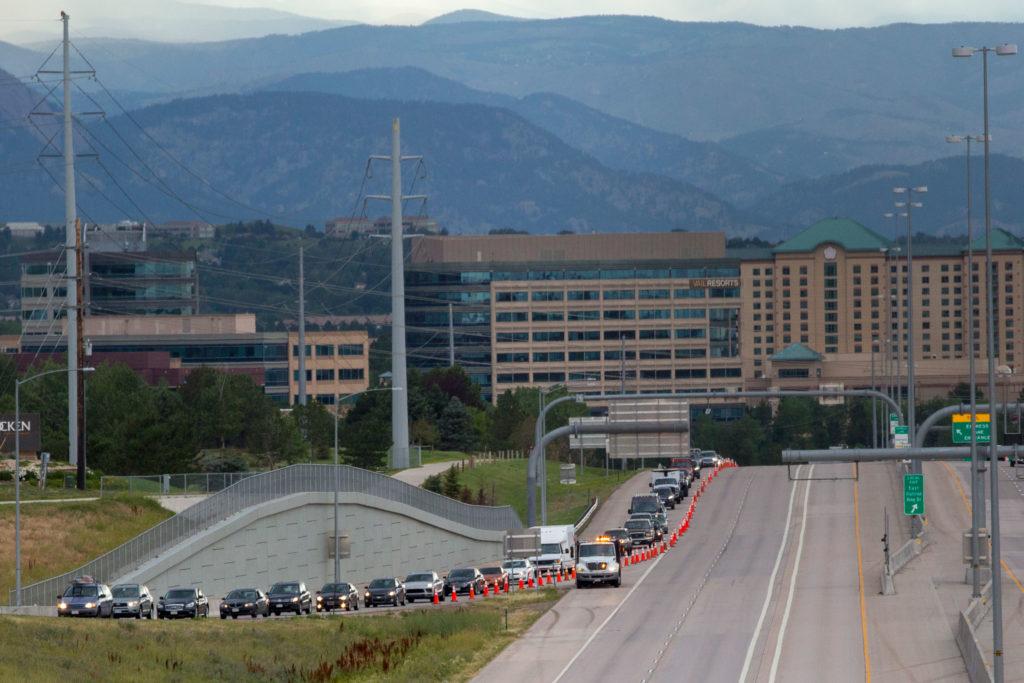

More than 107,000 cars, trucks and motorcycles pass through this stretch of highway per day, according to 2018 traffic counts from the Denver Regional Council of Governments.

Regional Transportation District buses use an express lane (with carpool vehicles) to ferry about 14,000 people per day during rush hours. The Flatiron Flyer can use the shoulder in snail-paced traffic. Those options will disappear with the new setup.

“If we’re losing lanes in that corridor, the first thing we should be doing is running buses because that’s going to be able to take more people more efficiently,” said Danny Katz, who has followed the U.S. 36 project since its inception as executive director of Colorado Public Interest Research Group. “Best case scenario, it actually results in longterm behavioral change. Worst case scenario, we get more people on buses for the next however many months and then they go back to driving.”