In a language school in downtown Denver, a dozen adult immigrant students speak in low tones to their classmates, practicing English grammar tenses for presentations in front of the class. A shy student from Thailand and her partner make sure to avoid eye contact with their instructor, so they don’t have to go next.

Winny Changthong is the last to speak. The assignment: Suggest some activities that might help your classmates challenge themselves. Speak about your own experience with that activity using as many past-tense verbs as you can.

Changthong begins suggesting her classmates make new friends who speak only English.

“I came to Denver like three months ago and I was scared to go out.”

She breaks down.

The tears well up and fall quickly before the other students have time to notice she’s upset.

"I’m lonely," Changthong says. She doesn’t have friends; she only has her husband to talk to. It’s hard.

“I am in the same situation,” says Beatriz Collins from Colombia, leaning over from her seat next to me. Changthong’s classmates rush to comfort her saying, “I’ve felt like that, too.”

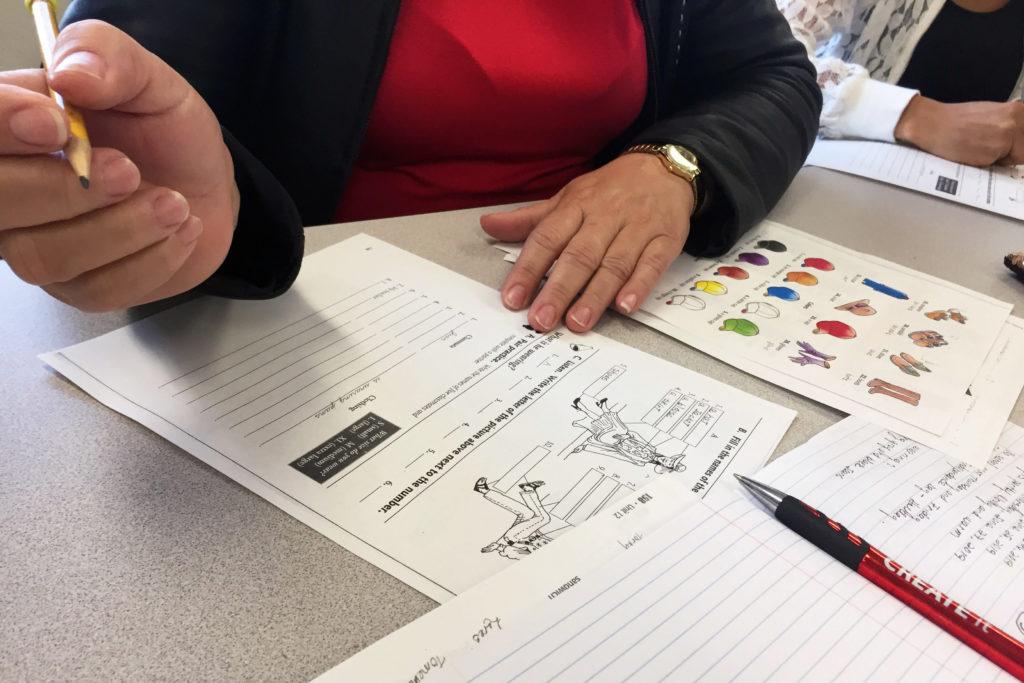

The class is all women — except for one man, a jokester. They’re dressed casually in jeans, T-shirts and polos sitting at U-shaped configuration of tables. They’re from Latin America, Africa, Eastern Europe, East Asia. The classroom has a world map on the wall.

“This class is your new family.”

“You can call us. You can have my phone number.”

“We are all in similar situations. Don’t be ashamed to talk about it.”

“Don’t give up.”

Anyone that has tried to speak a second language to native speakers knows how isolating it can be. As a child of one native Spanish speaker from Bolivia and one native English speaker from Seattle, I know that feeling all too well. When I speak Spanish to my own family members, I feel clumsy. I worry my loose grasp on the language makes me come off as inarticulate, dense and without personality.

But I have something these students don't. I know that soon I can go home to a place where most everyone speaks my language: street signs, police officers, coworkers and shop attendants.

Hidden in this place from public view, away from the overwhelming volume of cable news and Twitter, dozens of students file in. There are classes here for all types of English learners, but all the students have one goal in common: fit in in a new place — Colorado — and create a better life along the way.

“I live here for five years and it’s difficult, but every day is one challenge,” Collins says.

The most important thing for people like her, she continues, is to not be afraid to make mistakes.

“I really tried to go out by myself,” Changthong says, rubbing tears from her eyes. Then she found the classes at the Emily Griffith Technical College. She hopes to make some friends here.

“Even if we don’t understand between each other, we have Google,” another woman jokes in the classroom, pointing at her phone. Changthong laughs along with the class, and raises her hands in front of her nose, sniffling.

“And never stop smiling,” the woman adds.

Changthong sits in one of the most advanced classes Emily Griffith offers: high-level speaking and listening for immigrants.

“With the immigrant classes, those students come here with an intention that they have chosen. They have chosen to come to school,” said Sharon McCreary, a volunteer coordinator and English teacher for two decades. “They know what they need and what their deficit is, from a language perspective. They have a specific goal.”

Students in classes at the school are divided up both by language proficiency level and background of the student — immigrant or refugee, a legal classification made by the United Nations Refugee Agency.

The refugees are referred to the school through their resettlement agency. The school receives some funding from the U.S. government to teach these students.

“For our higher-level refugee students, they sometimes come in and think, ‘Well, I don’t really need this because I already speak English with some proficiency,’” McCreary said. “And then in our literacy level classes, we have students who maybe have never had formal education or stepped into a classroom. They’re not just learning English here, they are learning how to be a student and what that relationship is with the teacher and what the expectations are. That’s a huge difference from someone who has already been to school in his or her country.”

Some of the classes begin with a topic not many people think about: basic survival. They’re words to get around, about how to get on a bus, how to talk to a doctor.

Refugee literacy class teacher Kim Hosp says classes are loud and lively and charged with nervous energy. Many of Hosp’s students have been in the U.S. for less than five months.

Hosp engages the class in a call and response: “What are you wearing?”

The class echoes back: “What are you wearing?”

They take turns describing one of their classmate’s outfits: white shirt, blue jeans, black sneakers. And another: blue hijab, blue dress, brown sandals.

“Our refugee students feel motivated to learn,” McCreary said. “They understand why they need English, but they have a lot of other things going on that impact their language learning whether it’s trauma or health problems that have been neglected for years or just being overwhelmed at being in a new place where they feel terribly lonely and disoriented. All of that can make it harder to learn a language.”

The students’ skills run the gamut, McCreary said, from those who are not literate in English at all to those ready to take high-level proficiency tests for jobs or universities. Classes include speaking, grammar, conversation, reading, writing and even computer skills.

Emily Griffith also provides in-home tutoring for refugees in metro Denver. McCreary calls it “bringing English to the kitchen table.”

Volunteers spend time in homes tutoring people who can’t leave the house for traditional classes. That includes parents who don’t have access to child or elder care and those with severe post-traumatic stress.

Right now, the in-home program serves 135 refugees, but there is always a waiting list, McCreary said. The number of people they can serve is limited by the number of volunteers willing to put in the hours of emotional and mental labor to teach.

“It’s a really challenging volunteer assignment,” she said. “It’s not for the faint of heart, but cultural bridging is something that has been proven with data that is integral to a successful life and a successful integration for refugees here. That comes from us, the receiving community, making meaningful, long-term connections with refugees and lifelong friendships come out of that as well.”

I ask Collins if she feels people in Denver accept the English learners.

Collins pauses. She’s carefully considering her answer. It’s complicated.

“Sometimes yes, sometimes no,” she tells me. “No worrying for me though because I am concentrated on my goals. My goal is one day to speak fluent English.”

She said her English classes are supportive and a good motivation to learn and practice.

“I used to tell my students, ‘You’re in Colorado. Everybody loves to talk about the weather. If you can learn to talk about that, you can always have a conversation,’” McCreary said.

There’s something unique about learning English in Colorado, she said.

“We have a lot of transplants to our state,” she said. “A lot of people are new and even though they might be from this culture originally, they still have that feeling of disorientation, maybe a little loneliness.”

“As a state in general, we rate very highly on being welcoming to newcomers,” McCreary said. “This is a wonderful place for immigrants and refugees to come and feel like they can stay and they’re at home.”

Inspired by conversations with people in the community, we're taking a week to produce a short series of stories about Colorado through the lens of languages used here. Here's one at Denverite about how the attorney general's office is trying to do a better job of serving Colorado's Spanish-speaking fraud victims. The series is another way for us to consider our state and who lives here, but it's also a test balloon and a call for feedback and ideas — do you have a language-related story you think we should know about? Let us know: [email protected].