A baby wasn’t in the plans when Beatriz Navarro immigrated to the U.S.

In January, Navarro arrived in Colorado from Mexico “to work and to learn English.” She felt something move in her abdomen soon afterward. A visit to the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora confirmed her suspicion.

She was already five months pregnant.

Navarro doesn’t speak English, so she immediately worried what it would be like to have a child in the U.S. Her hospital, however, was ready with a suite of options to help Spanish-speaking patients: in-person interpreters, phone services and a new state-of-the-art video interpretation line. It allowed her to communicate with her doctors through the rest of her pregnancy.

She was still nervous when the doctors decided to induce labor. What would it be like, she wondered, to give birth when she couldn’t speak directly to the people trying to help?

“I thought they wouldn’t understand,” she said through an interpreter. “I thought they would look at me differently.”

Recent reporting and research have highlighted a maternal health crisis across the country. American women are more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than any of their counterparts in the developed world. Those rates are significantly higher among rural, minority and low-income women — and rising.

Mothers who don’t speak English face additional barriers. Through interpreters, mothers are able to ask questions and get medical information in their native language. Once the child is actually on the way, they can also be the only conduit between a doctor and mother for life-saving information.

Navarro’s interpreter was in the room with her when she gave birth.

“She always made sure I understood things, that I wouldn’t be scared and that everything would be simple for me,” she remembered.

Navarro gave birth to her daughter, Ainhoa, without any complications. She swaddled the child a recovery room before being discharged, admiring her rounded nose and thick head of hair. Just days after giving birth, she had already forgotten one detail of the experience: The name of her interpreter.

“I was very confused!” she said. “A lot was happening!”

“I Am The Patient's Voice”

Liz Lubelski, a Spanish interpreter at UCHealth, where Navarro gave birth, wasn’t surprised she forgot who assisted her in the delivery room. In her own work, she said it’s important to forget your own identity and become an anonymous medium between the doctor and patient.

“I call it ‘interpreter mode,’” she said. “When I interpret, I’m not Liz. I am the patient’s voice.”

It’s more than telling doctors what a patient said. It means conveying how the patient said it. If something is spoken with anger or fear, Lubelski has to mimic the emotion. If the patient lets out a barrage of curse words, she approximates the profanity.

That’s especially important during labor and delivery.

“Moms always say things with their faces and their hands,” she said. “Sometimes, in our Hispanic culture, we see doctors and nurses as figures of authority. So if they’re asking you a question, you might say ‘no’ when your face says ‘yes.’”

Those are moments when Liz Lubelski snaps out of the rapid cycle of translating messages back and forth. She tells the medical staff that “the interpreter will clarify,” then asks the patient a series of her own questions. Do they understand what’s happening? Are they confused? Is there something they’re ashamed of sharing?

Maternal health advocates say those moments can save lives.

Doctors often rely on women’s descriptions of their own pain to detect emergencies in the delivery room, said Kayla Frawley, a policy and advocacy director with Clayton Early Learning. If a hospital only provides over-the-phone interpretation, an option when in-person interpreters aren’t available, medical staff might not know when something is amiss.

“You lose cues. You lose time,” she said. “In those really high-emergency scenarios, which we see all the time, it can be a matter of saving someone’s life.”

UCHealth tries to provide in-person interpreters whenever possible. That’s why it has 44 medical interpreters on staff, all Spanish speakers, according to Scott Suckow, director of language services. He plans to hire a Russian and American sign language interpreter in the next month. For rarer languages, it contracts interpreters as needed.

The hospital tries to provide an in-person interpreter for all deliveries, especially when it’s a problematic birth or a C-section, but such accommodations can’t always happen.

“Sometimes, at three in the morning, it’s going to be difficult to find someone,” Suckow said. “Or if it’s a very rare language or dialect.”

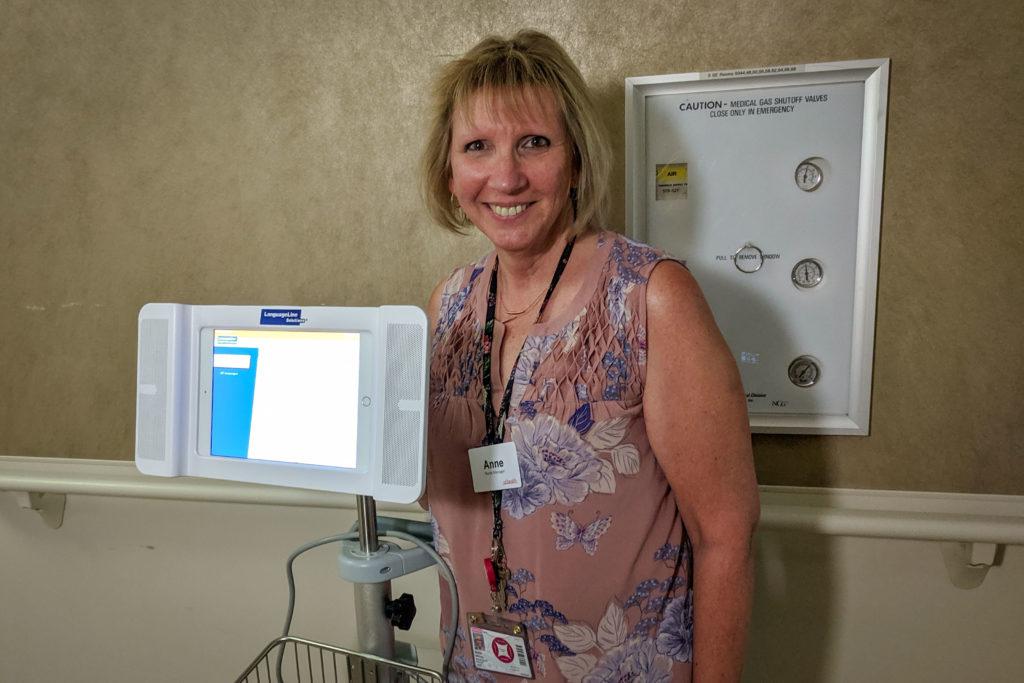

In those cases, the hospital still must meet federal legal obligations to provide interpreter services. In the past, nurses or doctors might have called an over-the-phone language line. Now, the hospital is experimenting with a new option in its women’s care unit: an iPad on wheels.

A study found medical providers tend to prefer video services above over-the-phone interpretation. In-person interpreters are valued even higher, while patients rated of the methods more or less the same.

Still, the legal requirements are no guarantee that medical facilities can help limited-English speakers. In Colorado, a 2004-2006 survey conducted by a coalition of progressive groups found only four in 10 hospitals had institutional guidelines for interpretation. It also found hospitals often enlisted patients’ family and friends as interpreters, which research shows carries significant medical risks.

A 2010 study provides more recent data at a federal level. It found hospitals can quickly provide interpretation for the second most common language spoken in their ER, but struggle with their third most common language.

If widely deployed, the video technology at UCHealth could vastly expand rapid access to languages services. The LanguageLine Solutions provided consoles offer instant access to over 250 languages. Just scroll through the options on the iPad, select one and an interpreter appears on the screen.

“It’s literally the best invention in interpretation I’ve seen in my 35 years of nursing,” said Anne Behring, the nurse manager for the mother-baby unit at UCHealth. She said the consoles have become so popular, she’s ordered trackers to make sure no one on her staff hogs the machines.

“Outside, It’s A Community”

Farida Nawrozi was three months pregnant when she followed her husband, Mukhtar, from Afghanistan to Colorado. The Taliban had made a threat on his life for helping the U.S. military. A rare special immigrant visa gave him and his immediate family a chance to escape.

When she arrived in Colorado, Nawrozi exclusively spoke Dari, one of the main Afghan languages. For her prenatal visits, UCHealth provided a couple of Dari-speaking interpreters to help her through the process.

One of them was Malalai Mommandim, another Afghan immigrant who had found interpretation work after years of volunteering at hospitals helping refugees and widows. Today, she makes a point of not just conveying messages for doctors, but also connecting women to a growing community of Afghani refugees around Denver.

“I just try to help them, show them where’s an Afghan grocery store, where to find a similar thing that they used to eat in Afghanistan,” she said.

After Nawrozi’s first visit, she and Mommandim exchanged phone numbers. They texted on a regular basis through one successful pregnancy, then another. Today, Nawrozi spends most days at home, caring for her 3-year-old daughter and 11-month-old son. She often needs advice.

“When she’s having some difficulties or some questions, she is calling [Malalai],” explained Muhktar, translating for his wife. “She is very helpful.”

Mommandim said she would happily do the work on a volunteer basis. She has had women break down and cry in the examination room, so relieved they were to hear their native language for the first time in a long time. She described helping one woman through a successful birth after a long string of miscarriages.

“At the hospital, I just convey messages to doctor, and doctor to patient,” Mommandim said. “Outside, it’s a community. We’re friends.”

Inspired by conversations with people in the community, we're taking a week to produce a short series of stories about Colorado through the lens of languages used here. Here's one at Denverite about how the attorney general's office is trying to do a better job of serving Colorado's Spanish-speaking fraud victims. And here's one about how Coloradans pronounce their place names in ways you might not expect (or be able to guess)! The series is another way for us to consider our state and who lives here, but it's also a test balloon and a call for feedback and ideas — do you have a language-related story you think we should know about? Let us know: [email protected].