On the floor of Pueblo’s Steelworks Center of the West — now a museum in what was the Colorado Fuel and Iron company steel mill’s medical building — three stripes in different colors run from room to room. They helped the mill’s many non-English speakers navigate their way to the appropriate service.

“They learned from other people that if they were here to see the eye doctor, they followed one color line on the floor. If they were here to see the ear doctor, they would follow another color line. If they were here for their physical, they would follow a third colored line,” Steelworks Center curator Victoria Miller said.

The Steelworks Center reports that more than 40 different languages were spoken in the mill and associated mines in the early 20th century. It was a place where immigrants could work in the New World without knowing English.

Colorado Fuel and Iron, at that point the largest steelmaker in the West and Colorado’s largest employer, was eager to accommodate the diverse workforce. The immigrants also made Pueblo the state’s most ethnically diverse city at the time.

Ethnic Enclaves

Vince Gagliano only spoke Italian until he was about 5 years old. It’s not because he came from the old country, although his parents did. It’s because he grew up in Pueblo’s Bessemer neighborhood, right across the interstate from the steel mill. It was where the city’s Italian families lived, and Italian was just about the only language anyone spoke.

“You know, I didn’t have to speak English until we moved out of this neighborhood,” Gagliano said.

He is now the fourth generation of his family to run Gagliano’s Italian Market, which stands among homes in the Bessemer area. The cramped and colorful shop offers imported Italian meats, cheeses, desserts and about 200 different varieties of pasta — though the Gagliano’s locally made Italian sausage is bulk of their business today.

“We still carry a lot of the products that my uncle carried in the 1920s. We still have almost the same customer base, but we're three or four generations down,” Gagliano said.

Growing up in the 1970s, he said Pueblo’s different ethnic populations still largely lived within their own enclaves. For instance, the Italians had Bessemer, and on the other side of Mesa Hill lived the Slovenians. Gagliano said the two did not mix well, and neither group traditionally visited the other’s neighborhoods.

Many of the workers at the mill came from Southern and Eastern Europe. Payrolls and photos from the time show people from around the world.

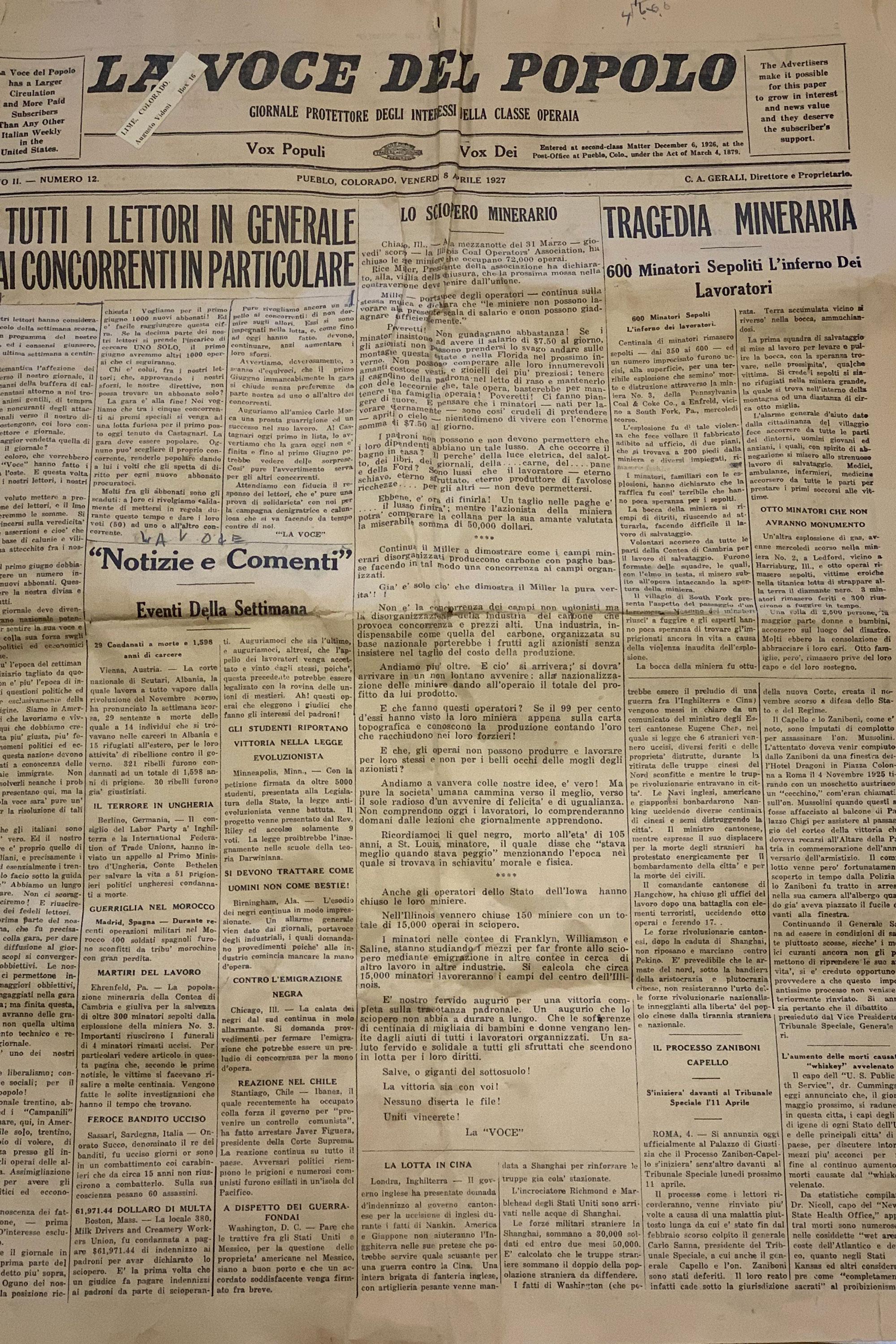

Miller said foreign-language newspapers flourished. She estimates at their peak, about 20 different newspapers in as many languages were publishing citywide with names like La Voce Del Popolo, Coloradeno, Pueblske Novice and Abruzzo-Molise.

Assimilation

Colorado Fuel and Iron did offer English classes to its workers and other courses meant to help them adapt to American culture. They largely worked.

Gagliano said he still speaks Italian about every day, but it’s just a little here and there — maybe responding to a foreign family member on Facebook. He’s not fluent anymore, and his kids barely speak any of the language.

This is true in ethnic communities across Pueblo — most foreign languages and cultures are fading. But also fading are some of those old rivalries. The mother of Gagliano's children came from the Slovenian community over the hill, the people the Italians were just not supposed to mix with.

“We ended up intermarrying,” Gagliano laughed.

Inspired by conversations with people in the community, we're taking a week to produce a short series of stories about Colorado through the lens of languages used here. Here's one at Denverite about how the attorney general's office is trying to do a better job of serving Colorado's Spanish-speaking fraud victims. And here's one about how Coloradans pronounce their place names in ways you might not expect (or be able to guess)! The series is another way for us to consider our state and who lives here, but it's also a test balloon and a call for feedback and ideas — do you have a language-related story you think we should know about? Let us know: [email protected].