It was a serendipitous discovery, albeit a disconcerting one.

Gregory Wetherbee, a research chemist at the U.S. Geological Survey, had been collecting rain samples to study nitrogen pollution. Instead, he found a familiar leftover of modern life.

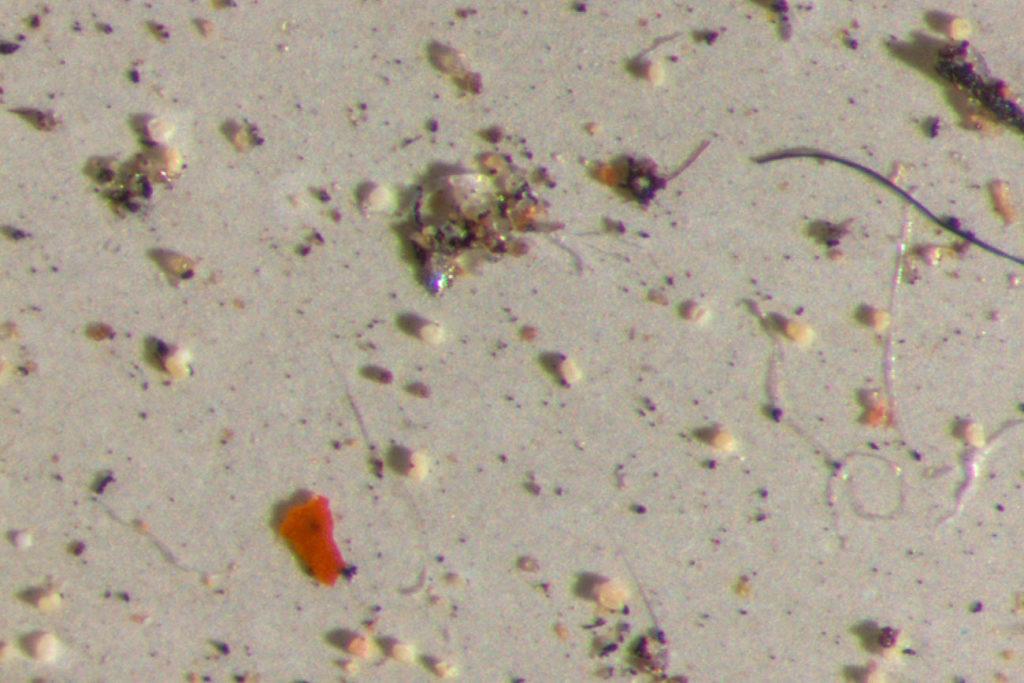

“I thought maybe I should look at these under a microscope. And when I did, uh, I was a little shocked by the amount of plastic that I saw in them … chunks of blue, orange, pink, you name it.”

Microplastics were the “furthest thing from my mind when we first started this project,” he said. Now it’s the focus of his new research paper titled “It Is Raining Plastic.” These plastics are tiny pieces of mostly fiber material, invisible to the naked eye.

As he stood next to a rain collector in a community garden in Arvada, it wouldn’t surprise you to find plastics in the water gathered here. This spot is close to traffic, parking lots, homes and stores. There’s a lot of plastic around. What really surprised Wetherbee was when he still saw microplastic in the rainwater collected at a site 10,000 feet above sea level in Rocky Mountain National Park.

“That made me realize that what we had here was something that was quite significant because the question is how do those plastics get into that remote area?”

Wetherbee’s study doesn’t answer that big question, and he doesn’t want to speculate. But it makes him think that somehow the plastic is transported through the atmosphere. A similar study was done in France that echoes Wetherbee’s findings. In a remote part of the Pyrenees Mountains, researchers found microplastics in the rainfall.

The study’s lead author told National Geographic that “Microplastic is a new atmospheric pollutant.”

Wetherbee said the plastic he found could be coming from myriad sources. Synthetic fibers from our clothing, shreds from tires on the road. When a grocery bag or a drink bottle breaks down, it becomes tiny pieces that spread. It doesn’t go away.

“Now, I can't get out of the car at the supermarket without noticing all the plastic trash on the ground,” he said.

Plastic is can be found everywhere: in the deep ocean, in the stomachs of whales, in seabirds, in the fish that we eat and in the water we drink. A study in Orb Media, with the University of Minnesota and the State University of New York, found that 94 percent of tap water samples collected in the United States had micro and nano plastics in it.

Alice Fulmer of the Water Research Foundation said that plastic in rainwater is just one example of the challenges around treating for tiny, man-made material.

“It's just that there's such an abundance that even removal of most of them can result in some getting through,” she said.

The sedimentation process — where gravity removes solids from water — gets rid of most of it. But she said no new methods have been implemented to try and completely remove the plastics from drinking water.

“I don't believe that we have enough information about the potential human health concern or environmental concerns to warrant any new treatment being installed or applied at water treatment plants.”

Fulmer makes the point that finding these plastics doesn’t mean there’s an inherent risk. And there is no definitive research on what impact consuming microplastics does or doesn’t have on human health.

The Water Research Foundation is involved in a project that’s looking at ways to remove microplastics from water. They’re also researching better ways to detect them in the first place. However, it’s important to look at the bigger picture, Fulmer said.

“We've got to then be having those conversations as a society and think holistically about how to prevent them from entering the environment and limiting exposure.”

Jack Buffington, an assistant professor at the University of Denver, has some ideas for that. Buffington teaches supply chain management and just released a book called Peak Plastic: The Rise and Fall of Our Synthetic World. He argues that the supply chain is responsible for the problem.

“We can create these materials at such a cheap price,” he said. “We can throw them away, we can produce them all over the world. We can ship them all over the world.”

Plastics weren’t designed to be in a circular system like aluminum cans are, he said. It’s easier and more economical to recycle aluminum products than to dig up materials and make them new. Plus, it doesn’t downgrade in the process. Buffington said plastic needs to be designed in the same way.

“Problem is, is that, how long is it going to take for that to happen? And what impact is it gonna have in the environment for that not to be fixed?”

Buffington posits that if plastic waste had value to a community it could be seen as a resource, instead of trash to be shipped off and processed somewhere else, likely overseas. Right now, only 10 percent of the 380 million tons of plastic produced every year is recycled.

“And think about these communities, they don't have natural resources,” he said. “But they do have waste. So waste could become their natural resources. Big companies are not looking to build manufacturing sites in these communities. So maybe these communities could create small manufacturing through waste.”

The first step would be to get people to understand the scope of the problem — just how pervasive plastic is in our environment, the issues it creates and what it means to our reality. Gregory Wetherbee, the researcher with the USGS, wants to get out the same message. That’s why he titled his paper, “It Is Raining Plastic.”

“It’s an emphatic statement about a condition that we believe is something that people should know about,” he said — that there’s more plastic in the environment than meets the eye.