A recently confirmed member of the state’s Independent Ethics Commission was investigated in 2016 for workplace harassment, ultimately agreeing to undergo counseling and spend six months away from an office she oversaw to avoid contact with employees who complained about her conduct.

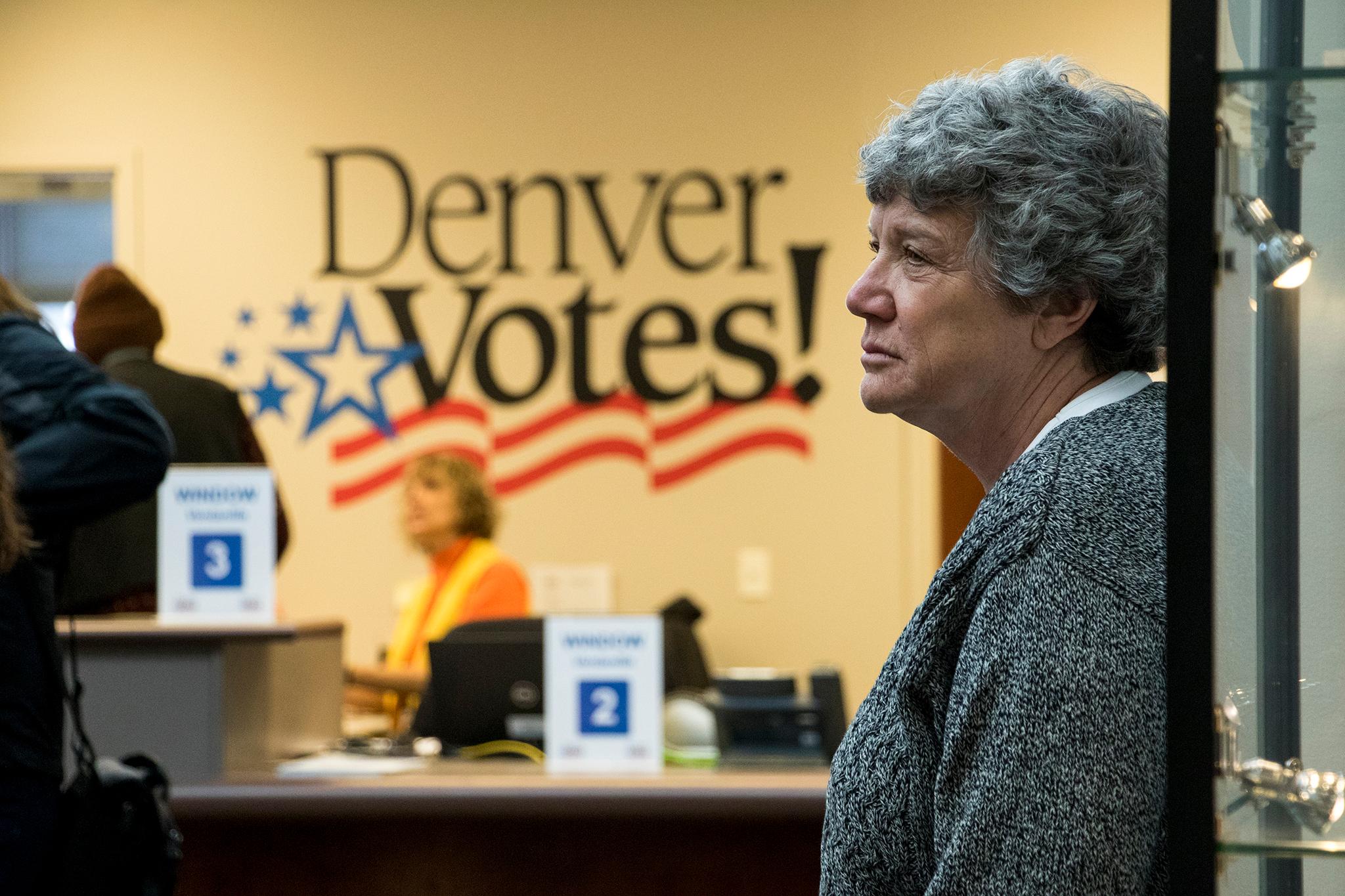

The investigation of former Denver Clerk and Recorder Debra Johnson, and the resulting agreement, have not previously been known to the public. The city of Denver paid nearly $30,000 for outside legal counsel to investigate the complaints and provide representation to Johnson during the investigation.

“We had one law firm who was hired to do some investigation and another law firm to provide legal advice,” said Karla Pierce, a supervisor of employment law at the City Attorney’s Office. She declined to give any details about the results of the investigation into Johnson.

“The way the statute's written, we shall not disclose complaints of sexual harassment and investigations.”

Colorado Public Radio obtained a copy of an agreement drafted by the City Attorney’s office in April 2016, which lays out a series of steps Johnson agreed to take to achieve "resolution of the current matter.”

The city said there were no records of settlement payments made to Clerk’s office employees who may have complained about Johnson and Johnson now denies that she harassed staff, though she apologized to a staff member soon after a complaint was made.

“Allegations are allegations until they're proven otherwise, and they were never proven otherwise,” Johnson said.

Johnson chose not to seek re-election in 2019 to a possible third four-year term.

In May 2019, the Colorado House of Representatives unanimously confirmed Johnson to fill a vacancy on the state ethics board. The unpaid position sits on a five-member panel in judgment of elected officials accused of violating ethics laws. It is a four-year appointment.

“We made some calls and did some vetting and I spoke to her specifically,” said Democratic House Speaker KC Becker, who nominated Johnson, also a Democrat, after she said Republicans in the House didn’t support her other choices. “She was an independent elected official. She didn’t have a boss. I haven't heard of any complaints and the research we did didn’t indicate any.”

The investigation into Johnson’s behavior began after an incident in February 2016 captured on a security video reviewed by CPR. Johnson allegedly pulled up a female employee’s dress during a gathering at the Elections Division. That division is part of the Clerk’s responsibilities but operates from a building separate from Johnson’s primary office.

The incident brought to a head multiple employees’ concerns that Johnson was at times inappropriate with staff. Elections Division Director Amber McReynolds, who worked for Johnson, took those concerns to the City Attorney’s Office.

After the city investigated, it reached an agreement with Johnson to temporarily bar her from coming into the elections office — including during the entire 2016 primary election for U.S Senate and state legislative seats and a portion of the time when mail ballots were being returned in the general election for president and other offices — and to undergo harassment training. Johnson did not admit wrongdoing and told CPR it didn’t impact how the elections were run.

“I don't think it impeded anything in terms of my work,” Johnson said. “I had great staff and they filled out the fulfillment of that office and their duties.”

The agreement states, “Debra will not drink at any work-related events or functions at which Denver City employees are present. Debra will not touch any Denver City employee (other than hand-shaking) and will not make jokes or references to or in the presence of Denver City employees that are in any way sexual at any work-related events or functions.”

“During the June 2016 election, Debra will not visit the Election Offices at 200 W. 14th Avenue unless there is a legal reason why she needs to do so, but instead she will only visit pre-agreed upon voting sites,” the agreement stated. It did allow Johnson, the clerk and recorder, “to be present at locations where election activities and public outreach events take place during that election cycle,” in order to maintain her role as a public face of Denver’s election efforts.

The agreement to steer clear of the elections office remained in effect until Nov. 1, 2016, about 10 days after ballots were starting to be returned in the general election.

Johnson also agreed to attend training on harassment and retaliation, and counseling on boundaries and treatment pertaining to alcohol.

“I don’t have an alcohol problem,” Johnson told CPR, adding that she agreed to the terms only to let the office get on with its work.

“Given the situation, both parties, we did what we needed to do to make sure that we can continue to run the [Clerk’s Office] and that's what we did.”

Two days after the incident in February Johnson emailed an apology to the woman.

“I sincerely apologize for my actions on Thursday and truly regret what I did,” Johnson wrote. “My behavior was inappropriate and I know I have caused grief and trauma in the Voter Recorder department. The trust and respect between us has been violated. I am a jerk and this type of behavior with not happen again.”

An investigation of Johnson’s behavior was launched a short time later.

After that investigation led to the agreement, McReynolds said she and other senior officials gathered employees together in June 2016 to tell them about the actions Johnson agreed to take. One current employee who worked in the office at the time, and asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, said he was hopeful that Johnson’s “inappropriate touching, off-color jokes, and heavy drinking” were being addressed.

“We were glad someone was trying to hold her accountable,” he said. “And we were pretty dismayed with what the city came out with, ‘I’m sorry this happened to you but there’s nothing we can do.’”

There is no city policy that includes a mechanism to remove an elected official from office or mandate disciplinary action in the wake of sexual harassment allegations or workplace misconduct.

“Elected officials are responsible to the citizens who elected them, essentially,” said Pierce, with the City Attorney’s Office. “I suppose an agency could adopt a policy that would have some consequence to the elected official if they so choose, but the reality is that no one has the authority to fire an elected official. They're basically responsible to the public and they can have a recall election or not be reelected.”

In 2018, the city updated its workplace policy to include a formal process for filing a sexual harassment complaint against an elected official, including the clerk and recorder. Pierce said it was in response to news stories about inappropriate text messages sent by Mayor Michael Hancock.

Under the new policy “complaints against the Clerk and Recorder will be promptly investigated, as appropriate, by a third-party investigator retained by the City Attorney's Office. The City Attorney's Office will coordinate the investigation and make recommendations based on the results of the investigation.” The outcome would still not be released to the public.

McReynolds, who was responsible for implementing the agreement with Johnson in 2016, said the city did not have a process in place to deal with this issue back then and she doesn’t think it’s strong enough now and needs more transparency.

“Employees deserve to work in an environment free from sexual harassment. Being an elected official should not exempt someone from accountability,” McReynolds said. “The answer to the employee cannot be either file a lawsuit, press charges, or go to the press.”

Ongoing Problems

The alleged incident that sparked Johnson’s investigation happened on Feb. 4, 2016 in the Denver Elections Division office. Staff gathered to take a picture to celebrate the Denver Broncos upcoming Super Bowl game. Various people held orange and blue balloons and people in the back row held a “Go Broncos” banner.

Three staff members who were present told CPR Johnson pulled up a female employee’s dress, exposing her underwear.

Security video from the office that day shows Johnson next to a woman who is kneeling for the photo. Johnson takes the woman’s hands and helps her stand up, and then Johnson approaches her. Someone steps in front of them and briefly obscures them and moments later the woman who was kneeling straightens and adjusts her own dress. Staffers who can be seen witnessing the alleged incident do not appear to have a visible reaction to it in the moment. Johnson walks away, as does the staffer.

CPR is not posting the video to protect the identities of staff members but has reviewed emails circulated in the office that day by employees who witnessed the incident and said they found Johnson’s behavior problematic.

“I feel upset, wanting to cry and embarrassed too because I didn’t do anything about it. I just stood there,” emailed one staff member. Another wrote “I was speechless as I watched (the complainant) try to save face and keep her composer (sic). I thought this to be unprofessional and distasteful.”

McReynolds offered counseling to upset employees the following week.

Minutes before the incident, the video also shows Johnson rubbing a balloon on a male staffer’s buttocks. It was not the first time Johnson’s behavior with this particular staffer had raised questions among other workers in the Elections Division. Another employee, who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation, said Johnson had a previous interaction with the man that made his co-workers uncomfortable.

“We were at a work conference and one of the other clerks had been drinking and put a dollar down one of our employee’s pants, and then Deb pushed it down further down the full front of his pants,” said the witness. “Honestly it may be a sign of the times. I tried to grab my phone. I tried to grab a picture because I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.”

The male staffer did not initially report either incident, but is one of two employees named in the agreement designed to protect them from Johnson’s alleged behavior. CPR is not naming them to protect their privacy.

The agreement with the City Attorney’s office stated that Johnson was committed to making sure employees had a comfortable and safe work environment, and in 2018 she paid $55,000 to hire an outside consultant, Robert Tipton, to examine the culture in her office. He interviewed 22 employees. His report concluded that “boundaries of professional conduct were not clear or respected.”

He also wrote that he observed “passive acceptance” of inappropriate language and derogatory and disrespectful language that was common “in the back office.” And a “Lack of oversight / awareness / ability / desire to correct inappropriate behavior / language.”

In an interview with CPR, Tipton described the workplace as “casual.” And he said it was overly familiar in a way that could hinder professionalism.

“People felt a sense of permission to use words that you might not use with your grandmother if she were present,” said Tipton, who finished his review in the fall of 2018. “And those issues were brought forward at times and nothing seemed to be done about it.”

By contrast, a citywide employee engagement survey from the previous year, using different methodology from Tipton’s, showed that 77 percent of the Clerk and Recorder’s employees were satisfied with their jobs. Citywide the satisfaction rate was 74 percent. And 68 percent of Denver election employees felt “Senior leadership is sincerely interested in the well being of employees.” Only 48 percent of employees across the city felt that way.

Ethics Commission

Johnson now has a new public role, this time statewide. The House Speaker announced Johnson’s nomination to the Independent Ethics Commission on May 1, 2019, to fill a vacancy. Becker’s House resolution lauds Johnson’s time as city clerk, including her efforts to improve election transparency, help institute mail voting, outreach to inactive voters, and her commitment to civil rights. Johnson was one of the few clerks to issue marriage licenses to same sex couples before the court ruled that Colorado’s ban on gay marriage was unconstitutional.

“On the basis of her extraordinary service as a public servant, her innovation and resolution of issues for the benefit of citizens, her passion for fairness, her impressive experience and knowledge, and her demonstrated integrity, Debra Johnson has demonstrated the qualifications that will allow her to serve as a respected member of the Independent Ethics Commission in an exemplary manner and to provide leadership on matters of ethics in a way that will reflect well upon the House of Representatives, the Colorado General Assembly, and the State of Colorado,” stated Becker’s resolution.

The House unanimously approved the nomination on a voice vote the same day the resolution was introduced.There was no discussion on record in the House. Two days later the legislative session adjourned. Yet, Johnson wasn’t Becker’s first choice.

“We were looking at a few people,” Becker said. “To pass an appointment to the Independent Ethics Commission, the House must vote on it and it must be a two thirds vote. And other names that I’ve brought to Republicans to earn Republican support didn’t garner their support. So I asked them who they would be willing to support and that was the name they came up with.”

Republican House Minority Leader Patrick Neville said he was not aware of any allegations of misconduct regarding Johnson.

“No, not any workplace misconduct,” He sent in a text. He said he made several suggestions for the commission at the speaker’s request. “I had worked with Deb around election issues and always found her to be fair and judicious even though we probably disagreed on most policy so she was one of the suggestions.”

The ethics commission typically handles financial complaints regarding Colorado’s gift ban and situations where elected officials may have improperly profited from their positions.

“It does seem like this is something that should have been public knowledge just from a public policy perspective rather than just kind of finding out about it,” said Jane Feldman, the former executive director for the Colorado Ethics Commission from 2008 to 2014, responding to allegations about Johnson. “I think that's probably a problem in the vetting process that maybe before somebody's name is put up for the commission, there should be a more thorough vetting process.”

The state legislature passed a bill in the 2019 session that would automatically require details of credible workplace harassment allegations against state lawmakers be released to the public. There will also be an annual report on the number of complaints, and the subsequent results. That’s not the case for local elected officials.

Johnson said she doesn’t think the details of the 2016 agreement will impact her ability to serve on the ethics commission and that the topic didn’t come up during her confirmation.

“It's a personnel matter. Why would they ask me about that?”