Say “Colorado” to someone and all the stereotypical outdoor activities are sure to come to mind: Hiking, camping, hunting, skiing and boating. Tourists — and locals — have running checklists of places they want to see and things they want to do. And whitewater rafting is often on that list.

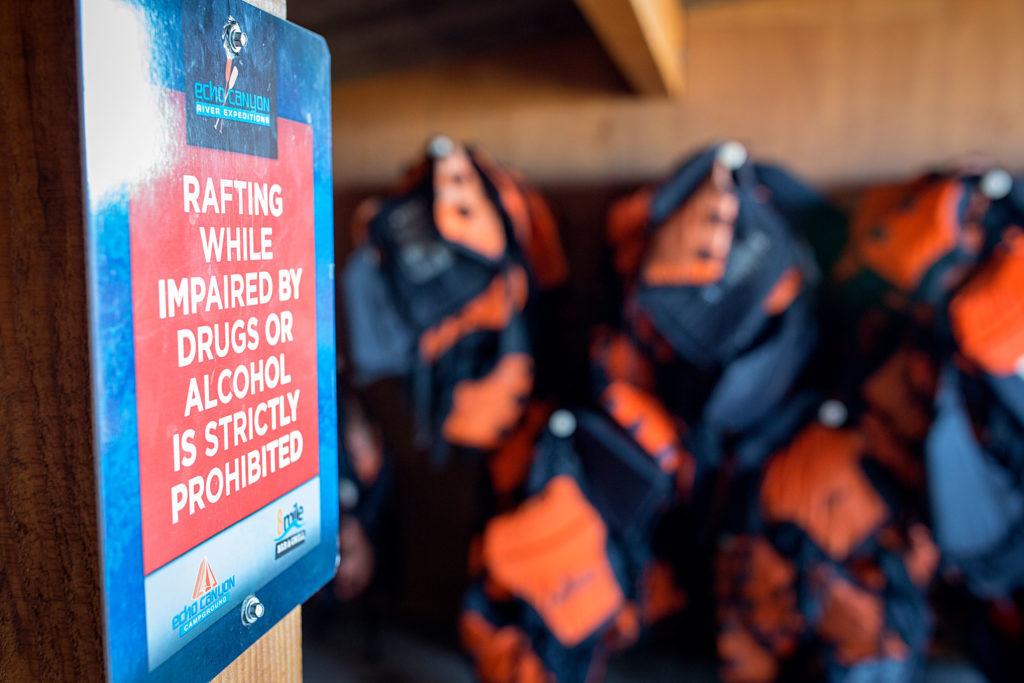

Hundreds of thousands of people go on a rafting trip with commercial outfitters each year, according to a 2018 review of river outfitter licensing in Colorado. And like any other adrenaline-pumping outdoor activity, this one comes with its own dangers, and people who are trying really hard to stop others from dying.

On average, eight people have died each year on Colorado’s waterways since 2009. Thirty-five percent of those fatalities have been with a commercial outfitter. This year’s number of fatalities is above average with at least 13 deaths on Colorado’s rivers, according to the American Whitewater organization.

The river advocate's count doesn't include an incident reported this week where a man was found dead in Boulder Creek.

People die doing other kinds of outdoor recreation in Colorado, though.

Colorado had 13.8 million skier visits during the 2018-2019 season, according to Colorado Ski Country USA. There were four fatalities last season, which doesn’t include those owned by Vail Resorts. Rocky Mountain National Park had about 4.4 million visitors in 2017, and 165 search and rescue incidents and five fatalities, the Coloradoan reported.

People Are Willing To Take The Risk.

Along with the thrillseekers come those who work hard to make whitewater rafting accessible and a good time, yet safe.

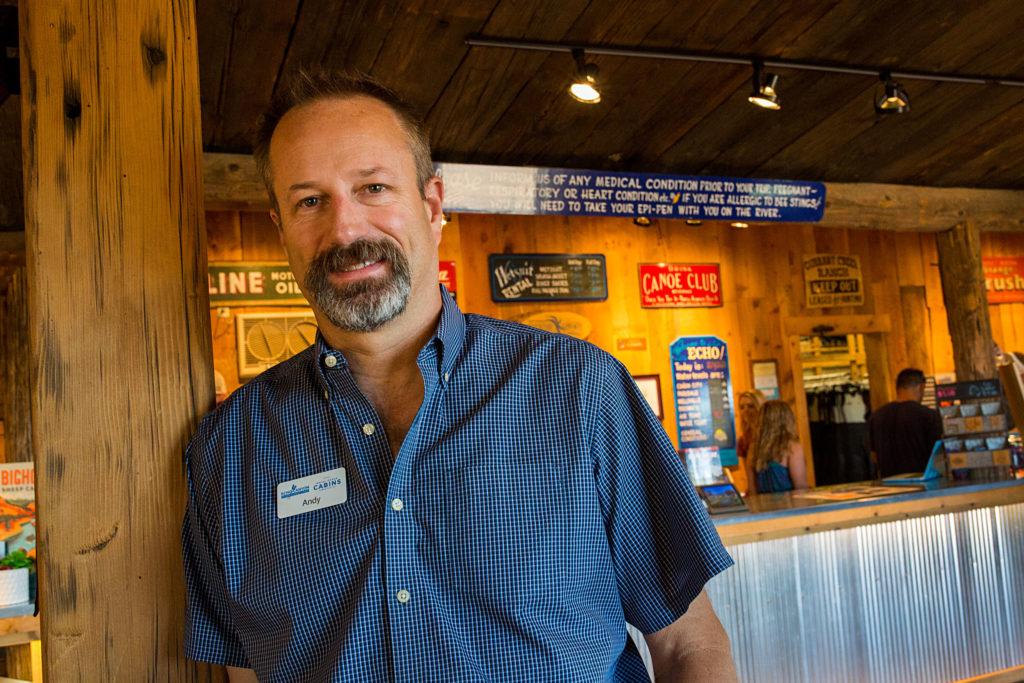

Andy Neinas has been in the rafting industry for 30 years. He owns and operates Echo Canyon River Expeditions in Cañon City and sees 25,000 guests each year. He said most people are from out-of-state, and if they’re not out-of-state, they’re likely Colorado residents entertaining their visiting friends and family.

“We’re the summertime equivalent of skiing in the winter,” he said on a warm and bustling Friday morning in July.

Guides were busy gearing up school buses to transport people to put-ins on the Arkansas River. They double-checked guest lists, counted supplies, then rounded people up to load buses.

Front desk staff made sure participants had appropriate clothing and asked about people’s medical history — heart or lung conditions, respiratory issues, asthma and allergies.

As a large group of boy scouts from Houston arrived on a bus, Neinas greeted them and told them what to expect on their trip. One scout asked how many boats have capsized this summer.

“I always tell guests please don’t be so naive as to think that your boat couldn’t go over… Part of the charm and excitement of being on a real whitewater rafting trip in Colorado is this is mother nature,” Neinas said. “This is the real deal. This is not an amusement ride.”

“When I saw the helmets, I think it got kind of surreal real quick,” he said. “I saw the big rocks.”

Marcos Andrade, a parent of one of the 13-year-old scouts and a first-time rafter, said although he was excited about the trip, he started feeling nervous when Neinas said the boats could flip.

'None Of This Is Meant To Scare You Guys'

Neinas doesn’t deny the risks and said the public perception of the industry definitely has an impact. But he thinks much of the responsibility for participant safety falls on the rafters themselves, who should be signing up for a trip that matches their skillset.

“The vetting process, or the determining of an appropriate experience for guests, starts with the consumer,” he said. “It does not start with us.”

Abby Leeper with Colorado’s Tourism Office said it encourages people to use the “Know Before You Go” principle. Coloradans and visitors alike should contact local ranger stations, the National Forest Service or a welcome center to get information and prepare for their trips.

“They can provide updates on water levels, trail conditions and other pertinent information,” she said. “We want people to be sure that they’re doing their research and checking conditions — really using caution when they’re recreating.”

Neinas said that customers should ask good questions and get good answers from an outfitter.

“We're in tourism. This is a customer service-oriented industry and we want to make sure that we're satisfying our guests’ expectations.”

According to a review by the state Department of Regulatory Agencies from 2012 to 2016, the most the state spent in a year to inspect commercial outfitters was $110,028. That number dropped by about $27,000 during the fiscal year 2016 to 2017 because there was a period of time when one of the positions was vacant. Three of the positions are seasonal rangers who work with a boating safety coordinator.

Andy Neinas, who owns the rafting company, said he thinks the industry is heavily regulated, and rangers do spot checks all up and down the river to inspect safety. The state requires outfitter’s guides to be at least 18 years old, have a valid first aid card, CPR training and 50 hours of on-river training.

Ricky Pazourek has been a guide on the Arkansas River for five years with additional boating experience around the world. He gave participants a safety briefing during the bus ride to the put-in.

“None of this is meant to scare you guys, but this is meant to inform you in case something was to happen,” he said, giving rafters options on how to react if they fall out of a raft. “We want you to be well-informed as opposed to just freaking out in the water,” he said.

“Everyone kind of shows up and doesn’t really know what they’re doing. Everyone thinks this is Disney World… Even something as simple as tubing down a Class I river, things can happen. It’s all about being smart.”

As guides unloaded the equipment after the bus ride, people bounced in anticipation, excited to raft the Arkansas.

Colin Glabinski of Chicago said he was a first-time rafter on vacation.

“I can swim so I’m not really too worried,” he said. “It gave me comfort knowing (our guide is) ready for anything so I’m ready.”