Back in the late ‘70s, there were happy hours in Denver’s working-class bars organized by artists for artists. It was a place to jaw about art and trade ideas.

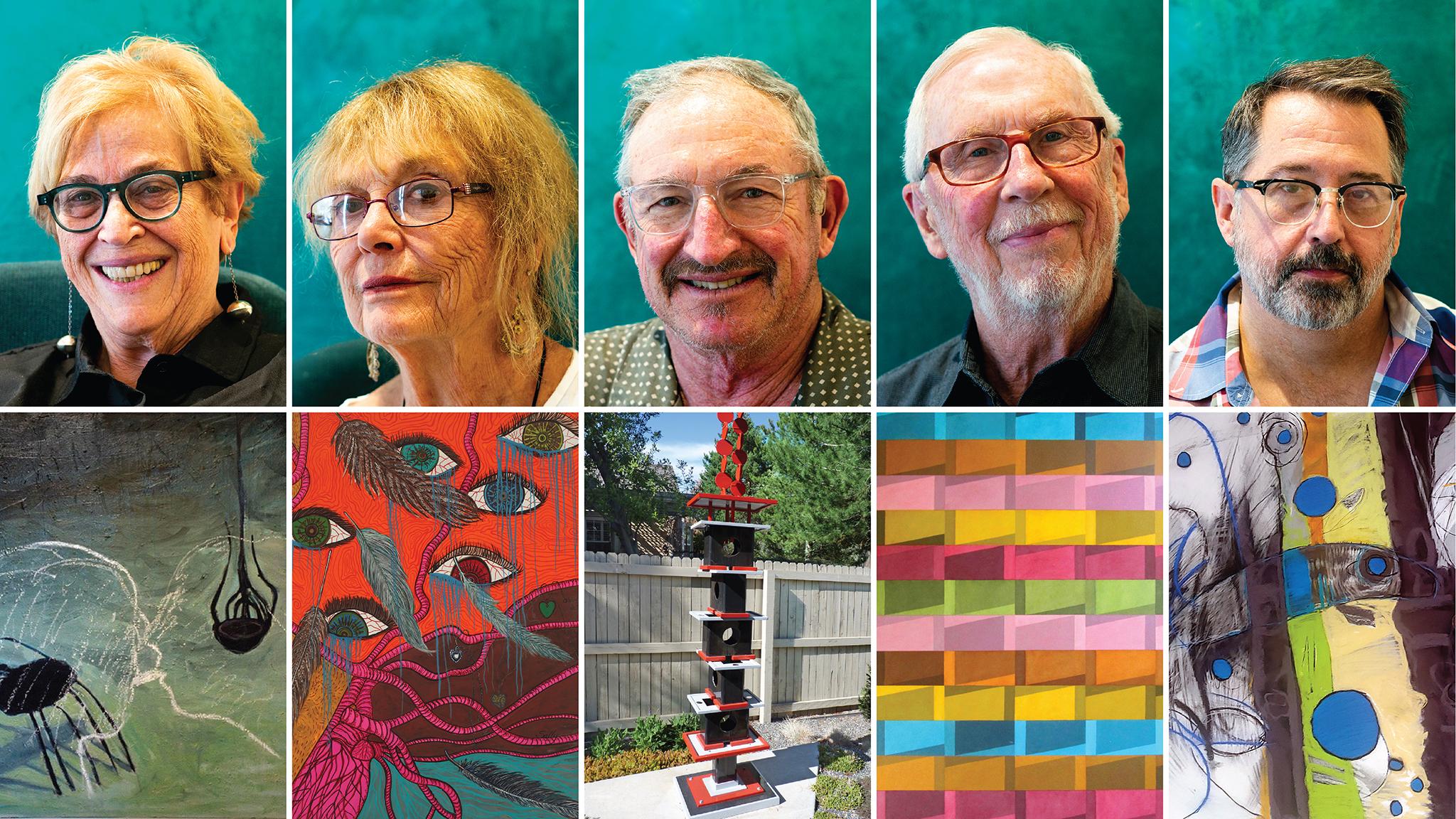

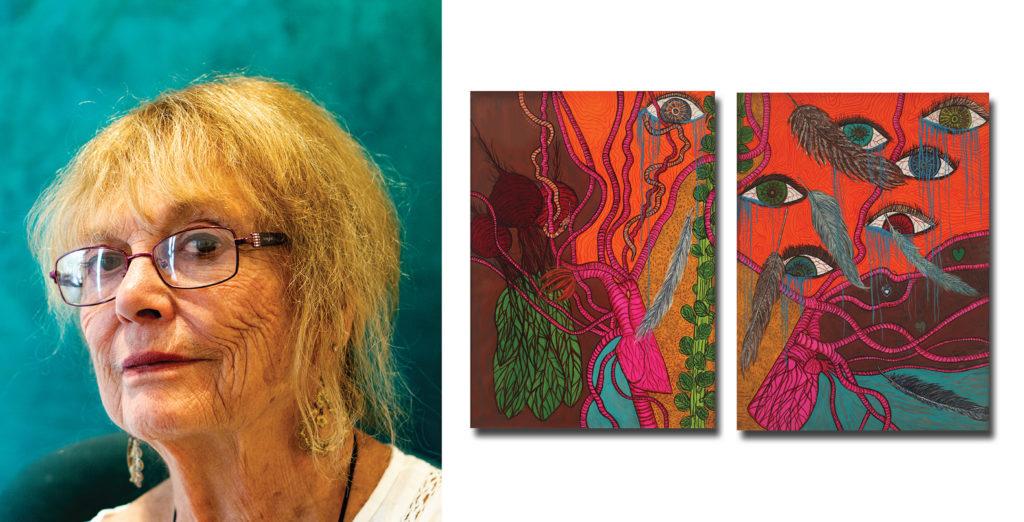

A common gripe among the “Art Bar” regulars was the lack of opportunities for contemporary artists in Denver and Boulder. Painter Margaret Neumann said most galleries, back then, were commercial galleries.

“I paint kind of odd, psychological paintings that are figurative and abstract at the same time,” she said.

She didn’t think her work would fit in with the commercial scene, and frankly, she didn’t want to join it. It was a sentiment shared by others, one that gave birth to the idea behind Spark Gallery. Neumann, visual artist Andrew Libertone and Jerry Johnson can be counted among the collective’s founding members.

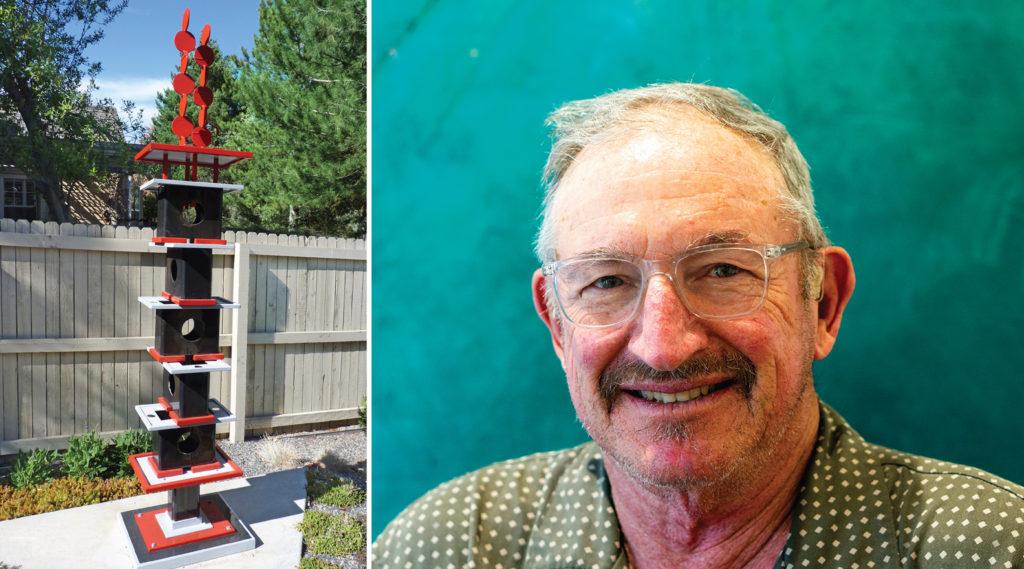

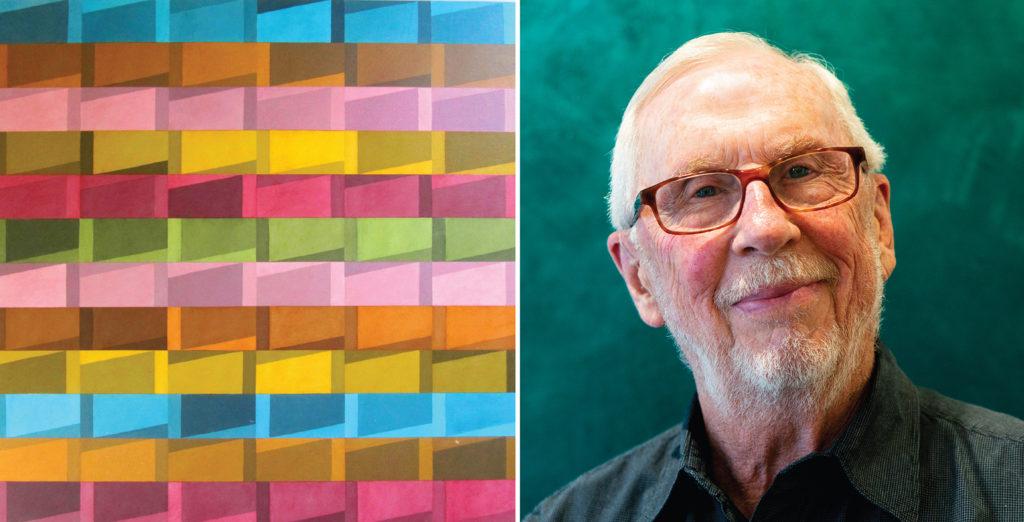

There wasn’t a single defining aesthetic of Spark’s 14 original artists, Johnson said. They were all simply tired of hearing their art was “too weird,” “too mathematical,” “too this” or “too that.”

“People wanted to do things,” he said. “I think having a co-op was a way of kind of empowering ourselves. If there’s no place to show, we’ll do it ourselves.”

And that’s what they did, they created a venue to show their art. A gallery whose name was inspired by Neumann’s “very bad dog,” Sparky. Other names they came up with were too pretentious, names like “Bolt Out of the Blue.”

“Who has a name like that?” Neumann said. “I thought, let’s just get real. Let’s call it Sparky’s. But that sounded like a bar.”

They simplified it to Spark. Something that they all decided was clear, easy to remember and most importantly, still distinct. The artists held their first show in late September 1979. They had managed to rent a vacated neighborhood Italian grocery in north Denver.

Libertone, who lived in the back of that original location, said a lot “grunt work” had to be done to get the place ready. They had to construct walls and figure out the lighting.

“It was a fairly rough situation,” he said of the learning curve. “But I think there was this certain energy that we were moving ahead in doing stuff.”

The grocery left Johnson with the memory of running a scrubber.

”It was a brutal job because the meat counter had been in the same place for years,” Johnson said. “And that floor over there was almost solid grease.”

There were no evites or email blasts in 1979. No Facebook or Instagram to post about a gallery opening. Back in the day it was mostly word of mouth to get people to show up. They reached out to friends, friends of friends, and basically asked, “Who do you know that we can invite?”

That led to a strong turnout at those early shows. But the co-op was a lot of work.

The artists ran the business side of the gallery, set up and took down shows, supervised the shows, balanced the books and they had to create the work to showcase in the exhibitions in the first place. Because of that, some of the original members didn’t stick around long. They tried to juggle the gallery with jobs and families.

Artists like Sally Elliott were more than happy to step in when a member departed.

Elliott joined about three years into the art venture. One of her favorite memories from the gallery’s original grocery location was working with neighborhood kids on art projects.

“We covered all the walls with paper and just let them paint whatever they wanted,” she said.

There were also graffiti artists hired to paint the gallery’s walls, she remembers. Oh, and that one time, in 1990, when artists Vaida Daukantas and Chris Thumblom had a performance art piece that involved housing live chickens at the gallery for three weeks.

Elliott is still a member and she feels at home at Spark. No one judged her for her style of art and no one judged her for being a woman, something that Neumann also felt.

“I was in school at a time when women were not considered on the same level,” Neumann said. It was like the men were the artists and the women were the chicks.”

In the mid ‘80s, Spark received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Part of it went toward publishing the Colorado Art Newspaper, a small paper that all of the members contributed articles to. Denver’s art scene was still pretty small at the time, but it was growing, and other artist co-ops popped up in Denver, like Pirate, which has since moved to Lakewood. The paper wrote about “the interesting stuff going on.” Neumann saw it as a way for the arts community to learn from each other.

“We got people to join in and that was a really important thing we did I think,” she said.

Around 1994, Spark moved less than a mile away from the Italian grocery to Denver’s Platte Street. After outgrowing that space, they landed next on Santa Fe Drive. Then, in 2017, the owner of that building, artist Lawrence Argent of Denver’s 40-foot-high Blue Bear sculpture fame, died. That left a question mark on the fate of Spark for some time, but they were able to breathe a sigh of relief when the new owner didn’t jack up the rent.

They’re still in the Arts District on Santa Fe today at 900 Santa Fe Drive.

Artist Mark Brasuell, current president of Spark and a founding member of EDGE cooperative gallery, said they recently signed a five-year lease on the Santa Fe Drive spot.

“I remember, [in the] beginning of EDGE and probably the beginning of Spark too, we would never think of signing a lease for more than a year, two years maybe max,” Brasuell said. “It would be like, ‘Oh my god, I don’t know if we’re gonna be around in two years.’”

Membership has been full for at least the last decade, Brasuell said and recently they’ve considered starting a waitlist.

As for the original members, none of them are still with the gallery. Many of them went on to work with other, non-co-op galleries as their once-considered-fringe work found a market.

Westword arts writer Michael Paglia noted in a recent article that some of the Spark founding members became “key contemporary artists to emerge in Colorado in the late 20th century.” He added that the cooperative has played an important role in “the big picture of this state’s contemporary art history.” Perhaps that could be attributed to the freedom to develop the work they wanted in the company of other artists.

The idea of an artist co-op was hardly new. But in 1979, the 14 young artists didn’t think to look elsewhere for ideas or research on how to run a co-op. Early on, they were always amazed they made it another week.

“It was really a step out,” Andrew Libertone said. “That we didn’t know what could happen and we just kept going with the energy.”

Denverite's Kevin J. Beaty contributed to this report.