Tony Garcia walks out of his office on the Auraria campus where he is a professor of Chicano/Chicana studies, and goes right next door to St. Cajetan Catholic Church, the church where he was “baptized, confirmed and later excommunicated,” he joked.

Both are on downtown Denver’s Auraria campus that houses three schools: Metropolitan State University, University of Colorado Denver and Denver Community College. It’s also where Garcia grew up.

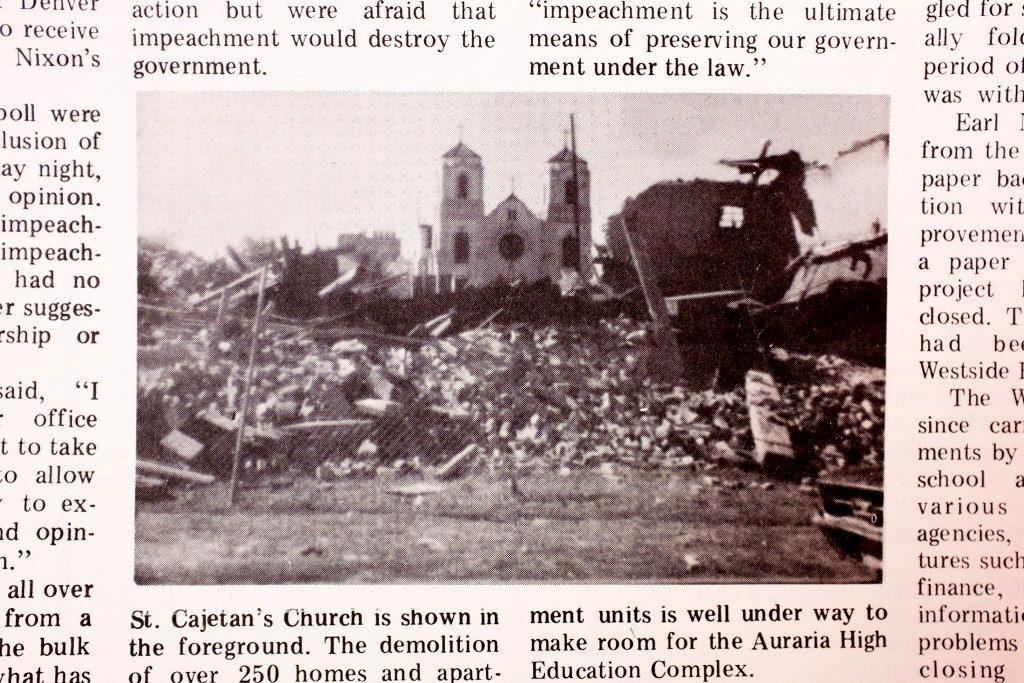

The campus used to be a neighborhood 40 years ago until the city saw the area as prime for “urban renewal” and displaced the majority Latino population in the 1970s. Now St. Cajetan’s hosts a computer lab.

As a way of making amends, the three schools established the “Displaced Aurarian Scholarship” in the 1990s to provide free tuition for four years of college for anyone who lived in the neighborhood between 1955 and 1973 — and their children and grandchildren.

The scholarships aren’t open ended. Many of the grandchildren are either in school or about to start school. Officials of The University of Colorado Denver, Metropolitan State University and Denver Community College said there are no current plans to extend the scholarship.

For some families like Noel DeLeon’s, this is the last generation who would be scholarship recipients.

If you look into Auraria’s history at the Denver Library, you’ll find that it predates Denver. Both were founded in 1858, but Denver came about a few weeks later. The two merged in 1860. Auraria has always been known as an immigrant town with both European and Mexican roots.

The neighborhood was a triangle bordered by Colfax Avenue, the South Platte River and Speer Boulevard.

Garcia lived in Auraria until he was 13 and continued to hang out there until the whole neighborhood was pushed out. He grew up poor, moving often, so he describes his neighbors as family. Everyone took care of each other. Neighbors hung out on their porch and played football in the middle of the street.

Garcia’s memories also include a segregated Denver. As he saw it, part of the reason the community was so tight-knit was that they knew they weren’t exactly welcomed past the neighborhood lines at Colfax and Speer.

“[Those lines] were protective for us, in a lot of ways because others didn’t come through here,” Garcia said. “The police acted a little bit differently at times, but it wasn’t a place where we were as vulnerable because we provided protection ourselves. But we also knew, if we traveled too far south, there were consequences,” he said.

The Auraria Higher Education Center campus was announced in 1968. Garcia remembers when the city came to talk about the plans for a possible campus.

“The pitch we were given was that ‘your kids are going to be able to go to school,’” Garcia said. “That’s what our parents heard. ‘Your kids are going to be able to change their lives.’”

Regardless, the neighborhood voted no.

In 1956, the city prohibited new construction of residential housing there. It was also during this time that legislators saw a need for more higher education facilities to accommodate the baby boomer generation by the time they reached college age.

The site had been targeted as early as 1965 in the mayor’s Platte River study under an urban renewal project.

The majority Latino population fought hard but ultimately lost in 1972 when relocations were complete.

Father Pete Garcia of St. Cajetan Catholic Church organized the Auraria Resident's Organization to fight against the Urban Renewal Authority. ARO was known for organizing protests and partnering with Catholic churches and the Jewish community to stop the removal.

The night before the election, Denver Archbishop James Casey read a letter from the pulpit telling all Catholics to vote “yes” for the campus. The next day, it passed with 52 percent of the vote.

The residents ultimately had to move. Many were compensated for their homes, but according to University of Colorado-Denver, some were just evicted and forced out.

Some houses on Ninth Street still stand — they are campus offices. The Victorian homes are now known as a historic site to the National Register and are declared as Denver landmarks.

The neighborhood might still have been around today if not for timing, Garcia said. The decision to remove the community happened before the Chicano Movement gained momentum in Denver in the late 60s and early 70s.

The legacy is so important to him that he makes a point to teach his students about Auraria’s history in his classes.

DeLeon is a Displaced Aurarian Scholarship graduate. Her grandfather was displaced. He died when she was a baby, but she believes that getting an education would’ve made him proud.

“Indirectly, he was able to give me an education and this blessing,” DeLeon said. “This is an opportunity to honor him as a person, do well, and thank him for the scholarship.”

DeLeon graduated with an accounting degree and is looking forward to getting a master’s. Her older sister used the scholarship and her little brother will soon start college.

She knew going to Auraria was going to be her path since her father first mentioned it to her in middle school. Before then, her parents had already prepared the paperwork to prove she was a descendent of an Aurarian.

“It really just made me appreciative of my family and their struggles,” DeLeon said. “I want to honor them through my hard work in school and to show them that I will utilize this scholarship to its fullest potential. I’m going to do well in all of my classes. I’m not going to waste any time.”

Despite losing his childhood home, Garcia still thinks the campus is about the greater good.

“Nobody can deny that education is important. This campus is one of the jewels of the state, I absolutely believe it,” Garcia said. “But the question is: on whose back is it built?”

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story misspelled the name of St. Cajetan Catholic Church.