Open space is coveted territory for hikers and mountain bikers. Hitting the trails in Westminster or Jefferson County can mean less traffic than a trip up the mountain to a crowded Rocky Mountain National Park.

Open space is wild-looking land set aside for preservation with the idea that it won’t be developed. Typically, voters weigh in on a tax to buy, manage and maintain it. And the city also doesn’t carve up the land into a park with picnic tables, baseball diamonds and jungle gyms.

The question is, how does something like this come about in a growth-hungry state like Colorado? E.J. Hassenfratz had never lived in a place that made such an effort and he sent Colorado Wonders to track that history down.

The ‘People’s Republic’ Sets The Tempo

Sixty years ago in Boulder, a more ambitious approach to the protection of wild or scenic lands emerged. For more than a century, local governments had made some preservation attempts but they were few and far between. Boulder residents though — stop us if you’ve heard this before — wanted to hold on to their city as they saw it and do something to slow development.

“The city council and city administration [at the time] didn’t want anything to do with it,” remembers 90-year-old Boulder resident Oak Thorne. “We got it on the ballot by citizens’ signatures. It was totally a citizens’ movement.”

The city’s population had nearly doubled between 1950 and 1960 with 37,700 residents. Today, 107,125 people call Boulder home. In 1959, a so-called blue line law forbade the pumping of water to new homes above a certain elevation. Ruth Wright, a retired lawyer and state legislator, called it a “stop gap measure” to keep growth from infringing on mountain habitat.

“There was always the thought that we needed to do more,” Wright said.

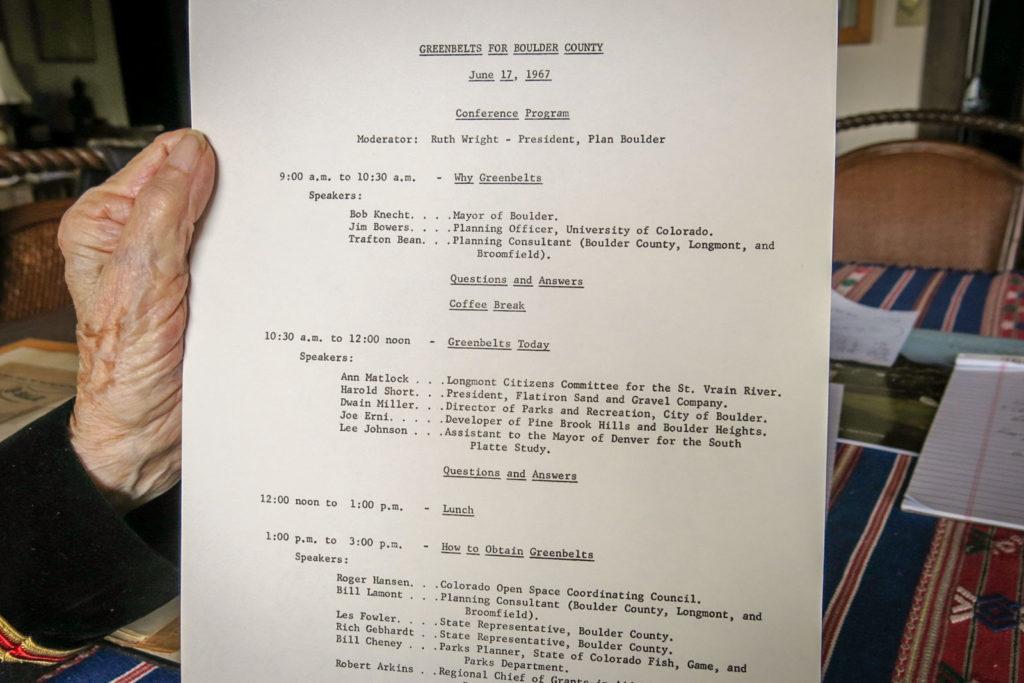

That opportunity came June 17, 1967, when Wright organized a conference on Boulder’s open space for city leaders. By the fall, Wright and supporters like Thorne landed a 0.01 cent sales tax on the ballot. Voters agreed for 40 percent of the tax to go to open space, with the remaining 60 percent going toward transportation.

“Boulder was growing at an enormous rate… and so there was this in-migration of people,” Wright said. “We didn’t want to stop the in-migration, but we certainly wanted to protect what we had.”

The experiment caught on next in Jefferson County in 1972. Westminster voters adopted an open space tax in 1985, becoming the second city in Colorado to do so. The Denver suburb set a very specific goal to preserve 15 percent of its landmass as open space.

“City leaders saw a lot of developments that were taking up lands that were very near and dear to people’s hearts in Westminster. So they saw a need to protect those properties,” said Rod Larsen, the city’s open space manager.

Lotto For Lands

In 1990, then-Gov. Ray Romer and then-Department of Natural Resources Director Ken Salazar started to look for more funding to bolster state park upkeep, wildlife protections and local open space purchases.

“There was a need to create a pot of money to support open space in the state… We could have gone for a statewide sales tax. There were options,” said Sydney Macy, then-director of the Nature Conservancy in Colorado.

A promising answer emerged in the form of state lottery dollars. In the ’80s, proceeds from scratch games and other jackpots streamed into small state park projects like campgrounds. Much of the money also paid for new buildings and other construction. In 1992, Macy and other environmental advocates campaigned to send 50 percent of state lottery dollars to a trust fund named Great Outdoors Colorado.

A second wave of cities and counties created open space programs, spurred on by matching cash support from GoCo for land purchases. One of the crowning achievements came in the early 2000s with the 21,000-acre purchase of the Greenland Ranch in Douglas County.

“It would forever mean that Colorado Springs and Denver would never grow together,” said Macy, who worked on the Greenland Ranch open space designation.

Are We All Full Up On Open Space?

Now some early open space programs have begun to shift into a new phase of operations. Westminster reached its 15 percent preservation goal in 2017. Open space acquisition is still a priority, said the city’s Rod Larsen, but land is a lot less affordable than it used to be.

“People see open space as the No. 1 asset in the city. It is the face of Westminster,” he said. “We’re constantly trying to find and maintain a balance and harmony between development and open space.”

In Boulder, there’s also an eye toward less land acquisition. If finding a house in Boulder is an exercise in patience and a fat wallet, then finding large swaths of land is even more of a challenge. Additionally, the Open Space and Mountain Parks budget is expected to drop $5.8 million to $29.6 million in 2020.

Interim Director Dan Burke said this is a move the department has planned for five years.

“We’re getting a lot more information, a lot more knowledge of what it actually costs to operate our system,” he said. And it costs a lot more to just maintain Boulder’s 155-mile trail system across 45,000 acres than ever before.

The next challenge for Boulder could come in the form of preparing open space for a future with climate change. Burke is set to discuss a new plan for this future with the city council in early September. He and other open space employees have spent more than a year hashing out with the public what they want to see in the plan, what should be prioritized and what should be left out.

“Getting the community engagement process right is very important,” said Burke, who’s sat in his share of packed meetings.

Because if there’s one thing he’s learned during his tenure in Boulder, it’s that residents care deeply about what happens to their open space land.