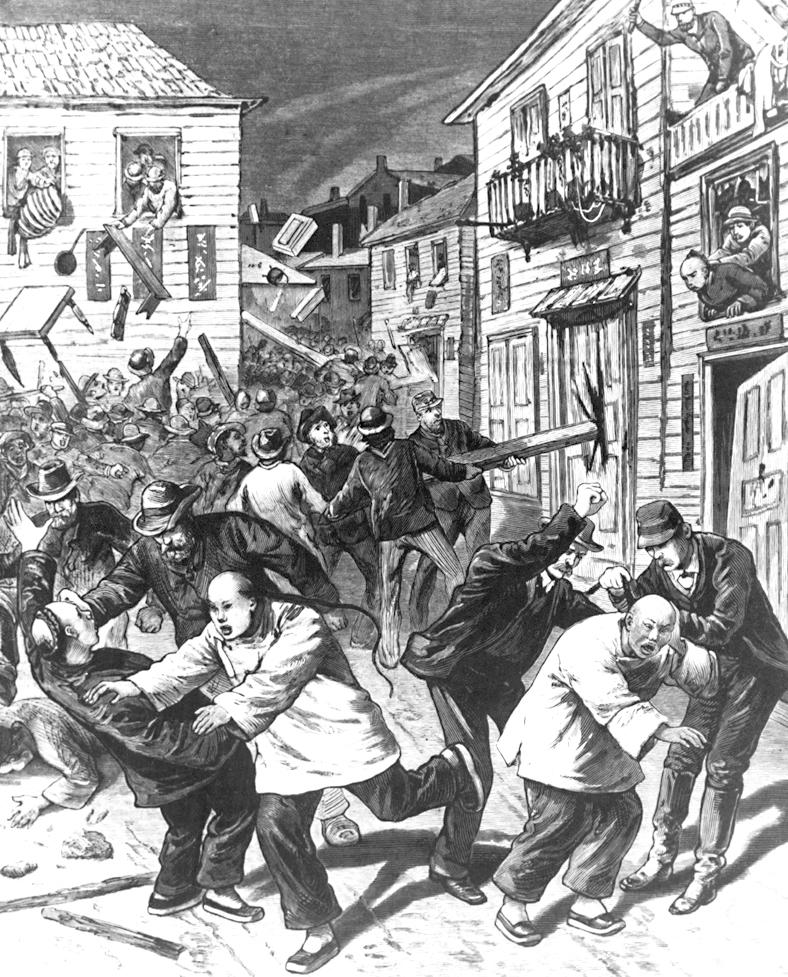

It was the first race riot in Denver’s history.

On Oct. 31, 1880, an argument broke out between Chinese and white patrons at John Asmussen's Saloon on the 1600 block of Wazee Street. In the 19th century, that stretch of downtown Denver was the city’s Chinatown, also known as Hop Alley.

“When the Chinese slipped out the back door, they were attacked and beaten, beginning Denver's first recorded race riot,” a plaque commemorating the riot reads. “About 3,000 people congregated quickly in the area, shouting, ‘Stamp out the yellow plague.’ Destruction of the Chinese ghetto ensued.”

That was almost 150 years ago. Many people were injured and one Chinese man died, a laundry worker named Look Young who stumbled into the riot and was beaten to death. About 150 claims were filed, totaling more than $30,000 in damages, but no Chinese residents were paid for property or business losses.

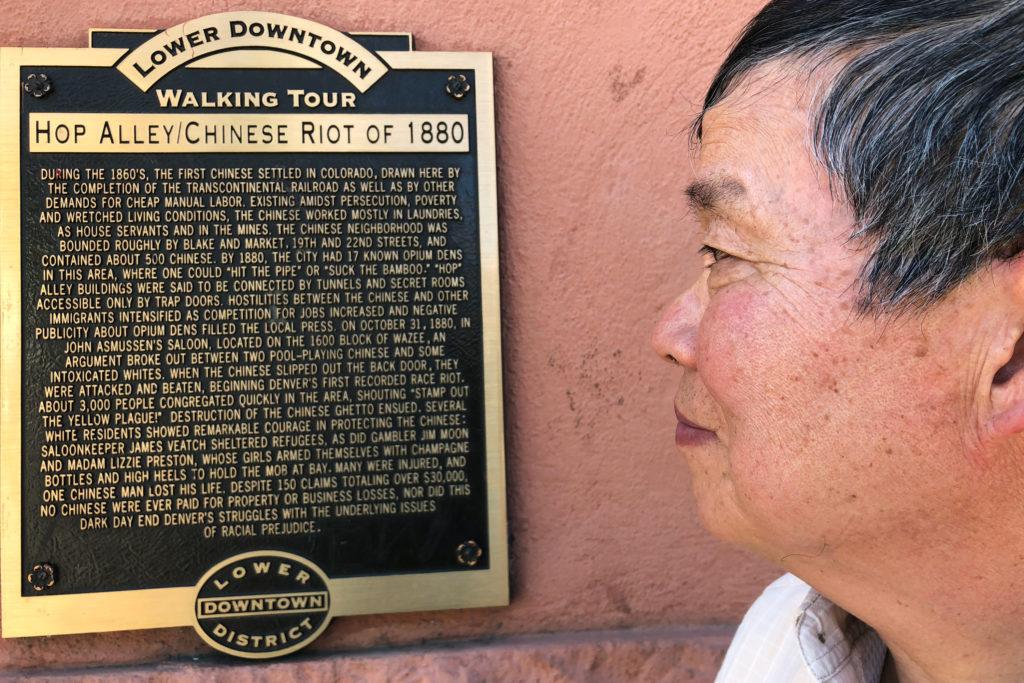

That plaque is on a busy street corner just across from Coors Field. In the opinion of William Wei, Colorado’s new state historian, its description of the riot and others are too often told through the lens of white historians.

“If you read this plaque carefully, you notice that it does not actually dwell on the victims of this race riot, the Chinese,” he said. “Instead, it focuses on the heroes who came to their rescue. Let me say that I applaud the heroes who came to their aid, but it does reflect a certain attitude that persists today. The need … to have a white savior.”

While the plaque honors and names the white saloonkeeper and customers who helped keep the mob at bay, it does not name Lee or other victims.

“They're not apt to identify the victims because that would humanize the experience, which I think they should do,” Wei said.

It was not the first or last problem that Denver’s early Chinese community would face. Chinese workers who helped build the Western portion of the transcontinental railroad were laid off after it was completed.

“They were in effect, dumped on the Western labor market. Ultimately, the Chinese were employed mainly in the mining industry,” Wei said.

Those who ended up in Denver were plagued by accusations of purveying opium (that’s where the name Hop Alley came from). There were 17 opium dens in the city back then, and 12 of them were located in Chinatown. But it wasn’t the Chinese fueling the opium business.

“The major customers were Denverites, white folks,” Wei said. “They would come down to Chinatown and to participate in what today we would call drug abuse.”

In serving white customers, Chinese people found one of the few jobs available to them.

“This was one of the few ways they could make a living,” Wei said.

One man, Chin Lin Sou, was considered a pioneer for the Chinese community.

“He was considered the mayor of Chinatown. It was an honorific that was given to the one individual in the community who could speak English, as well as Chinese, and serve as an intermediary between the mainstream community and the Chinese community,” Wei said.

Sou came from Southern China and worked from the railroad before settling in Colorado like many other Chinese immigrants. He worked primarily as a labor contractor, and is honored for that in a stained glass window lining the old state Supreme Court chambers at the Colorado State Capitol.

Wei will serve as the state historian for the next year, and he plans on highlighting the stories of Coloradans of color during his tenure.

“There are a number of things that I would like to focus on. One of them is to talk more about the minority, if you will. Communities in the state, they have been oftentimes overlooked, misunderstood, and the facts about them have been distorted. This would include not just Asians, but Hispanics, Native Americans, and others as well,” Wei said.

“Why not write about the Chinese, the Japanese and other Asians in the state? It is in a sense my responsibility to do so.”

Editor's Note: This story has been changed to correct the name of the Chinese laundry worker who was killed in the riot.