The woman who inspired a new state law prohibiting sheriffs from holding people at ICE’s request in local jails continues to fight her own deportation — with a very uncertain future.

Claudia Valdez Sandoval, 40, sobbed through parts of her final deportation hearing on Tuesday as she described the violence she suffered at the hands of the father of her three children.

How, during a particularly violent battle in 2012, she scratched him on the nose, causing him to bleed. She told her oldest daughter to call the police and when sheriffs deputies arrived, they incarcerated her for a week. She has been fighting to stay in the United States and raise her American-born kids ever since.

Sandoval doesn’t have a criminal record — in fact, she won a $30,000 settlement from Arapahoe County after she was wrongfully held in jail as a victim of domestic violence. ICE was tipped off to her presence when she was in custody there, and she was then held by local law enforcement for longer than she would have after ICE requested it.

In most cases, this isn’t legal anymore.

Gov. Jared Polis signed a law in late May banning local law enforcement from holding undocumented immigrants for longer than their sentences, or after they’ve posted bail, at federal immigration authorities’ request.

State Sen. Julie Gonzales championed the measure in the legislature and has been the paralegal on Sandoval’s case since the beginning.

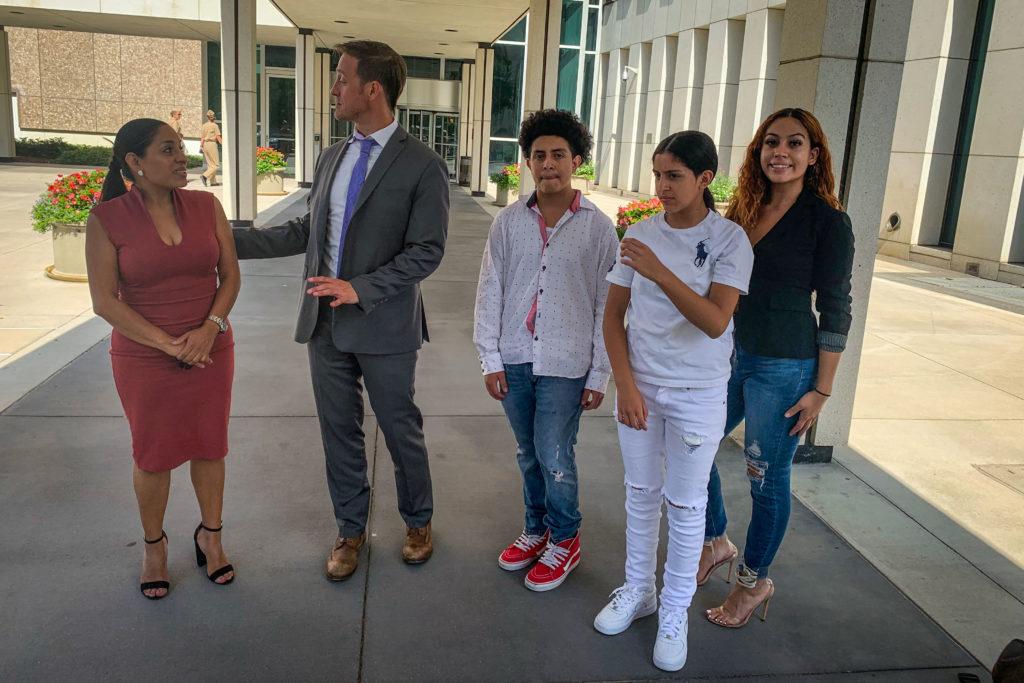

“ICE detainers are not warrants and unless they’re accompanied by signed orders from judges, then they have no basis to detain an individual,” she said, standing near Sandoval outside immigration court on Tuesday. “I think our work sends a message to ICE that the law applies to them too.”

Federal officials have criticized the new state law part of Colorado’s “sanctuary” policy. They say it’s helpful when local law enforcement hold people for up to 48 hours longer than a sentence when ICE requests it because it gives officials the time to get to the jail.

“We will continue to warn the public that these misguided sanctuary laws put individuals and communities at risk by releasing criminal aliens without notifying ICE first,” said John Fabbricatore, acting field office director for ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations in Denver, in a recent media statement.

Immigration advocates and attorneys disagree. They say it’s important to maintain firm lines between local law enforcement and federal immigration authorities in order to keep communities safe. If people fear police and are afraid of calling 911, it’s more likely that crimes — including domestic violence — will go unreported, they said.

Hans Meyer, Sandoval’s attorney, likens her case to someone getting arrested for marijuana possession after voters approved legal recreational marijuana.

“Her circumstances created conditions to have a conversation about reform,” Meyer said. “What we need now is a little bit of justice for Claudia. She was really victimized here.”

Sandoval arrived in the United States with her cousin in 1999 when she was in her early 20s.

She told the immigration judge on Tuesday she felt dependent on her partner of 13 years — despite his continuing verbal and physical abuse — because she didn’t speak English and was unemployed with three small children.

After the 2012 episode when she was jailed for calling the police, she made the decision to get her own apartment and a job. She now works in housekeeping at a retirement home and has raised the kids alone in Aurora with $1,200 a month from their dad.

Meyer is fighting to get a green card for Sandoval, citing a “hardship” legal argument. He said it would create undue suffering for her children if she were deported. Her three kids, aged 18, 15 and 13, have all suffered mental health problems and anxiety from their violent upbringing and their mother’s uncertain future. One of them had a panic attack on Tuesday in the courtroom during the civil immigration proceedings.

“It’s been draining to be waiting and waiting and waiting for a final answer,” Valdez’s 18 year-old daughter, Nicole, said. “I was so scared for this day and now this day is over.”

The immigration judge, Eileen Trujillo, declined to make a bench decision Tuesday. Meyer said it could be two years before she makes a final determination.

Until then, Sandoval continues to wait.

“I am still nervous,” said Sandoval, speaking Spanish quietly outside. “It was a lot of pressure … I’m going to go back to my normal life, to my job, to learning English.”