On Sept. 10, 1969, six and a half miles south of Rulison, Colorado, a 40-kiloton nuclear bomb exploded in the subterranean depths of the Piceance Basin.

The device, more than twice as powerful as the weapon at Hiroshima and with muscle equivalent to 40,000 tons of TNT, was an unorthodox tool in a grand experiment to free natural gas and kickstart a boom. The nuclear age wanted to give the oil and gas age a hand up.

“It felt like a very slow-moving tremble,” Parachute resident Judy Beasley said. “It was like a flowing of energy [underground].”

Miles closer to the blast zone it “was like a train rushing up the canyon,” Lee Hayward told Look Magazine in 1970. Hayward’s family owned the land where the experiment took place.

“Cliffs started pouring rocks. It was quite a show, really,” Hayward said.

Go back 50 years and the scene in Parachute (in 1969 it was referred to as Grand Valley) felt almost festive. Enterprising types peddled souvenirs. While a few dozen activists protested, most locals like Beasley had the afternoon of the blast off work. Everyone was told to be outside at the 3 p.m. detonation time for fear the shot would damage buildings and cause injuries. Roadblocks were set up and a throng of reporters, G-men, scientists, congressmen and foreign observers descended on this sleepy section of what is now the I-70 corridor to bear witness.

“We were whooping it up,” Beasley said. “We were really fortunate that we didn’t have that much damage.”

In the end the blast caused few problems for the locals. Some chimneys lost bricks, including Beasley’s. A few pickle jars fell to the ground in her pantry.

Several couples who lived within five miles of Hayward’s land ignored the evacuation and rode out the detonation. The wife of William Rankin told the Associated Press they planned to get their dogs into the station wagon and then “have a picnic down in the corn patch.”

As much as times change, the promise heard in many rural towns remains the same. There are much needed jobs and economic development underfoot, we need only unlock the riches from tight shale and other stubborn rocks. Rulison was perhaps the grandest vision of that ever put forward on the Western Slope.

In Hindsight, This Wasn’t A Job For An Atom Bomb

Drill rigs and well pads dot the landscape today. Garfield and Mesa counties — along with state-leading Weld on the Front Range — transformed into energy powerhouses thanks to advances in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, a process where a mixture of water, sand and chemicals is forced underground to free the fossil fuels within.

But in the 1950s, the idea was that a bomb might be better.

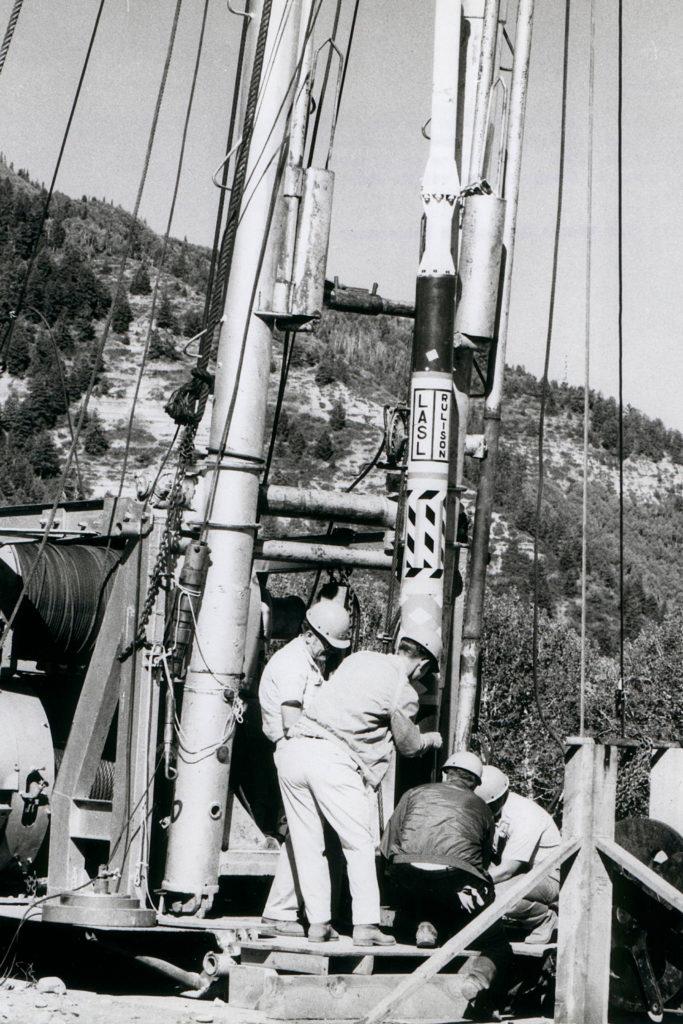

The Project Rulison 40-kiloton nuclear device is lowered into its 8,442-foot deep emplacement hole on Aug. 14, 1969.

Robert Campbell, right, and California congressman Craig Hosmer visit the well head at Project Rulison Surface Ground Zero.

Part of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory contingent at Ground Zero Site, of Project Rulison, seen here capped until the explosive was inserted. Dr. Robert H. Campbell, left, was the operations director for the project.

Project Rulison was part of a much larger government initiative called The Plowshare Program. It was an effort focused on peaceful and commercial applications for nuclear explosives after World War II.

“It boggles the mind that people would believe in this stuff, but if you put yourself in the minds of the Plowshares people, this is progress, this is modernity, this can be done,” said Scott Kaufman, the author of “Project Plowshare: The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Explosives in Cold War America,” a 2013 history book.

“They saw [Rulison] as an alternative to fracking that in their minds would be cheaper, it would do a better job, and therefore companies involved in the effort would make a lot more money.”

Houston, Texas-based Austral Oil and CER Geonuclear Corporation footed 90 percent of the freight while the federal Atomic Energy Commission, now the U.S. Department of Energy, picked up the remainder of the trial balloon’s cost. In a community thank-you advert found in the archive at the Rifle Branch of the Garfield County library, the chairman and president of Austral practically gushed about the possibilities.

“We are proud to be a permanent part of this community, and in the months and years ahead, we will do our best to be good neighbors and merit the support you have generously given us. We are confident — that as our program progresses — we will be able to produce natural gas from Rulison Field by nuclear stimulation, safely and economically, to benefit your communities, your state and our nation.”

Rulison wasn’t the first attempt to give oil and gas development an atomic lift. Plowshares tried the concept first in New Mexico. Project Gasbuggy used a 26-kiloton thermonuclear bomb just 4,200 feet underground but there was too much contamination in the result. The scientists behind Rulison hoped a device that relied on nuclear fission instead of fusion would produce far less of the radioactive element tritium. No radiation was released into the air after the Sept. 10 shot and the initial results indicated a success — and Plowshares gave the green light to another test.

That next experiment took place May 17, 1973, in Rio Blanco County, 35 miles northwest of Rifle with three bigger bombs — but that’s another story.

Modern Rural Living At Surface Ground Zero

Today the Rulison site is mostly forgotten. A small, tombstone-like monument stands sentinel in an open field behind a fence that says “No Trespassing.” As it was in 1969, Surface Ground Zero remains in private hands. The test was never on government land.

Coreen Hamilton owns the 26-acre stretch of land where the blast cavity lurks underneath. A previous landowner built the log cabin that Hamilton lives in, which she purchased last summer.

“We find surprises every day,” said Hamilton. “That’s cable wire,” she said as she pointed to black cord jutting out of the dirt that used to bring electricity to the site. She pointed to a second slab of concrete. “There’s a pad.” That’s where the generator stood.

Hamilton was drawn to this land because the view is breathtaking: aspen groves and oak scrub nestled between steep rocky sandstone cliffs. Wild turkey and elk wander the property, often headed to get water from nearby Battlement Creek.

Hamilton purchased the Rulison blast site with her eyes wide open. Her front door is less than 90 yards from the marker.

“The realtor advised us of what went on. They said, ‘I know you love the home and the view. But you need to do your research,’” Hamilton said.

The most recent water samples analyzed by the Department of Energy show no radioactivity. The government says radioactivity has never been detected in soil samples near Project Rulison, before or after detonation.

“Coming from the Denver area of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, they have homes built on that,” Hamilton mused. “Now they’re finding, years later, radioactivity in certain places. It couldn’t be any worse living down there than it is living up here.”

But why even split the atom under this beloved land?

“This was 1969, there was a depression in the area,” Judith Hayward said. Her husband Lee, now deceased, told her that his father, Claude Hayward, was promised a monthly check by Austral Oil once the post-blast gas started to flow.

The money never came.

“For years they have been telling us the oil shale around here would bring people back… but it hasn’t happened,” Claude told the Houston Chronicle in September 1969. “We’ve had hard times. The young people move away to the cities and the old ones wait, hoping something will happen to save our town.”

The Bomb Didn’t Bring The Boom

Economic development remains a challenge in Parachute. The population has hovered above 1,000 for more than a decade. The oil and gas industry isn’t as visible here as the town’s five marijuana dispensaries.

“People get very uptight and upset about fracking. [Project Rulison] was big fracking,” said Judy Beasley, who along with her husband served 32 years in various city offices in the town of Parachute, including mayor.

Since 1969, the town has had its shares of booms and busts. The most notable came in 1982 when ExxonMobil pulled up stakes in the region on a $5 billion shale oil project. More than 2,000 jobs evaporated in the Black Sunday bust and people and businesses fled the valley.

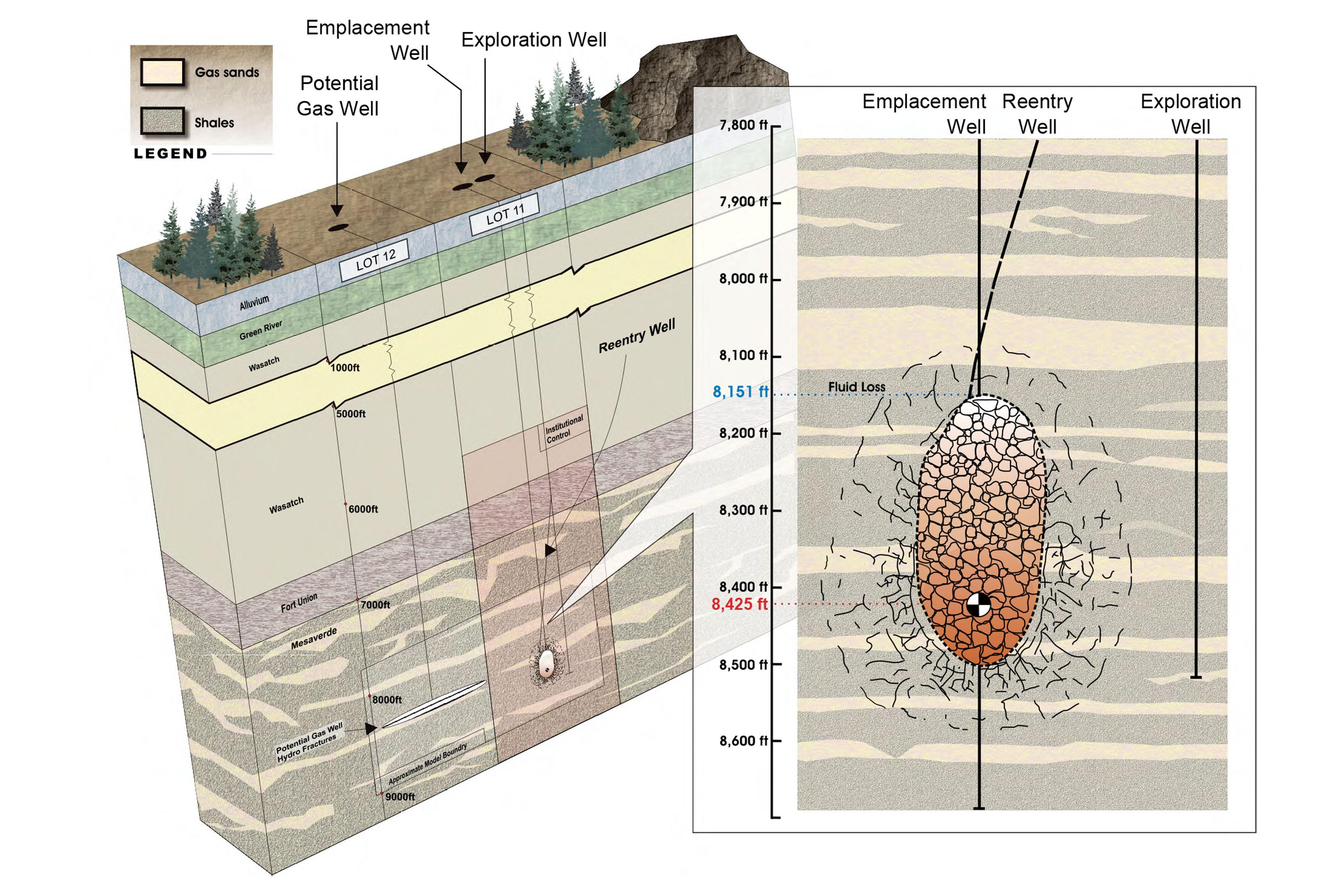

Between 1970 and 1971, Austral Oil used a reentry well to test and burn off some natural gas. Samples were found to be tainted with a small amount of radioactivity. Once that was detected, flaring was shut down. The company struck out when the market turned its back on the Rulison well, but a larger field of natural gas remains underground and conventional development has moved in to tap it.

Data from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission shows a few producing wells nearby. Coreen Hamilton sees the truck traffic on high mountain roads as they visit the sites to the south of her home.

In addition to annual 47 years of water sampling around the site, Project Rulison site manager Jalena Dayvault with the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management said some natural gas wells are also sampled within a 1-mile radius of the epicenter.

“The frequency of the sampling is based on the production of the well itself,” Dayvault said. “So we might be out there sampling on a monthly basis to begin with, and then reduce it quarterly. It all depends on how much gas that well is producing.”

State officials have their own testing regimen for nearby oil and gas operators. Wells proposed within a half-mile of ground zero must have a special meeting with the COGCC to weigh the project. Outside of the half-mile zone, there are soil sampling requirements. Some rules were relaxed in 2017 after decades of tests had shown negative results.

Even still, living near the site of an underground nuclear test makes some uneasy.

“They should have a permanent monitoring station set up out there,” said Ben Tipton, who along with his wife Sharon have fought modern-day energy exploration near their Battlement Mesa retirement community.

Ursa Resources has completed the first phase of its project in Battlement Mesa. It has proposed additional stages of a much longer regional project but has yet to start them.

“The federal government are the ones that set this off,” Tipton said. “They shouldn’t be holding off one bit.”

In fact, the Department of Energy plans to do the opposite and will move to “greatly reduce” the frequency of water sampling near Rulison in 2020.

“We may still collect a couple of samples that homeowners or somebody may want us to collect,” Dayvault said.

Judith Hayward shares the oil and gas concerns expressed by some of her neighbors. She voiced them back in the early 2000s when the Grand Valley Citizens’ Alliance challenged state regulators all the way to the Colorado Supreme Court over a proposed oil and gas development near Project Rulison. And still she shares them today.

“I don’t believe there’s any radiation,” said Hayward, who spent the better part of two decades on the project land with her husband Lee. But even still, she doesn’t have any intention of leasing the mineral rights she owns along with other family members under Surface Ground Zero for development.

“This needs to just be set aside because of what they did down here,” she said.

For its part, the federal government has its own restrictions. In the 40 acres around the blast, companies are prohibited from drilling deeper than 6,000 feet. The bomb cavity sits at the bottom of an 8,425-foot shaft. This information is even engraved on the memorial marker installed in 1976.

Coreen Hamilton’s concerns are more immediate and less atomic.

“Beer bottles, beer cans, snacky wrappers… people, they don’t care,” she said of the visitors who sneak onto her land to take pictures of the small Project Rulison marker. It’s impossible to read it without trespassing.

She’s spoken with the Department of Energy about an interpretive sign that tells Project Rulison’s story — one that can be read from the road.

Until then, she can expect more visitors. Some even come to her house to talk about the monument. One day brought the great-grandson of a Rulison scientist who wanted to see where his relative had worked 50 years ago.

“When they start talking I try not to interrupt,” Hamilton said. “I just try to sit back and listen.”

History is all that remains. The Plowshares Program faded away, its fate sealed by the lack of commercial success, public consciousness about radioactivity and the will of state voters. After the subsequent Project Rio Blanco experiment faced similar scrutiny, Coloradans approved a constitutional amendment in 1974 that requires voter approval before any nuclear device is detonated in the state. That leaves the Centennial State as a unique place where the people hold the power to grant permission for both new taxes and nuclear bombs.