Wildfire is a continual threat in the West, but researchers say an invasive species of grass that’s taking hold in states like Colorado, Wyoming, Nevada could make things worse.

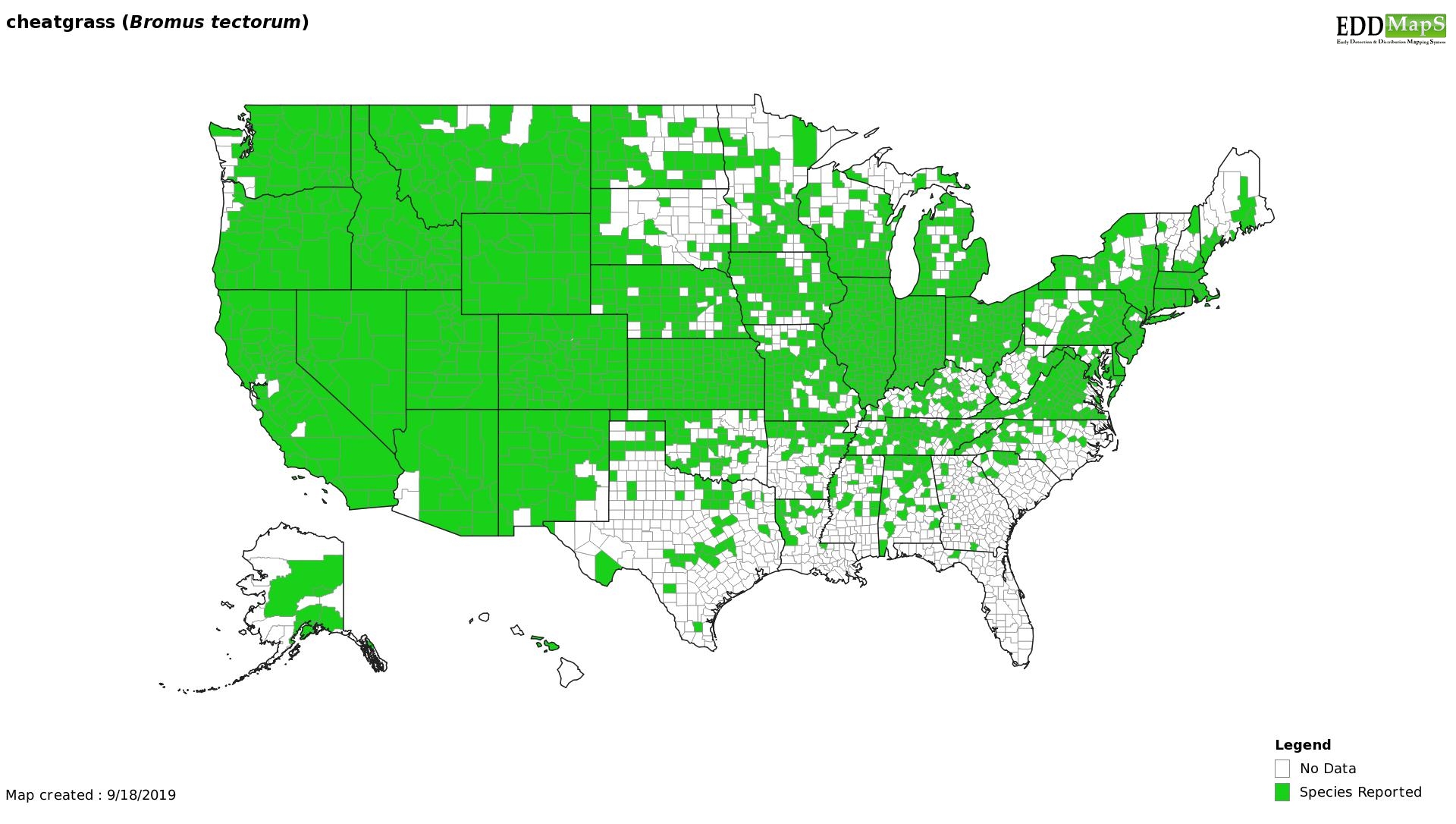

It’s called cheatgrass and it’s gradually taking over rangeland across the west. It grows quickly in soil disturbed by grazing, tilling, development and even fire. In Colorado, the Bureau of Land Management says cheatgrass on the land it manages is most prolific in northwestern portions of the state. Data from the University of Georgia shows it was found most abundantly Boulder County but it’s been observed across the entire state in varying degrees.

Walking through a field near Westcliffe, you’ll find knee-high patches of sage, throngs of wildflowers including asters and indian paintbrush, and cheatgrass. Guinevere Nelson is the Colorado State University extension agent for Custer County. She picks a handful of a reddish grassy plant, pointing to the bristly awns hanging from its stem.

“This is the cheatgrass,” she says, gesturing to the pointy pieces at the end of the plant. “So this is going to get into your socks, and into your shoes, and into your pants.”

If that sounds familiar, you’ve likely encountered the invasive weed just like the patch here on land owned by rancher David Huber. He says he’s spent close to $100,000 on fire mitigation on the more than 400 acre ranch.

“Inside our property we’ve thinned considerably and we’ve also limbed all the trees above about five or six feet,” he says. “So if the grass does burn here, there’s less of a chance of it putting the trees on fire.”

In 2011 the Duckett Fire came dangerously close to Huber’s home, burning more than 4,000 acres of Forest Service, BLM and private land. He says so far, managing cheatgrass hasn’t been on the forefront of his wildfire prevention efforts. If conditions continue to be favorable for the grass, though, that may have to change.

The thing about cheatgrass is that it’s highly flammable. A blaze last year in Nevada -- the Martin Fire -- spread through cheatgrass and eventually claimed more than 435,000 acres. And with this year’s wet spring, the weed is in full force. By this time of year, cheatgrass is dead. It turns a rusty brown color and becomes a thick, continuous dry fuel that leaves behind a layer of seed on the ground that can be viable for as long as four years.

Extension Agent Guinevere Nelson said cheatgrass germinates faster than most native grasses, outcompeting them for space and nutrients.

“People call it cheatgrass because it can have about two cycles that it'll grow and release seed and then grow and release seed again,” she explains.

The weed was initially brought over from Eurasia, most likely with grain. But it was also introduced in the 1800s as an anti-grazing grass—something livestock typically doesn’t like to eat.

So now, places like Westcliffe are left with stand after stand of a highly-flammable invasive weed that is really difficult to control and constantly looking to spread. Nelson describes the worst case scenario for the future as “everything cheatgrass all the time.”

“It provides no real habitat for your bugs or your birds or any kind of reptiles or anything. It's of no ecological value to the systems here,” she says.

Landowners have a few options to deal with cheatgrass including early grazing, pulling the weed out of the ground, and chemicals. Shannon Clark is a postdoctoral researcher in the weed research lab at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. She’s familiar with the ranch owned by David Huber. She’s conducted studies there, looking at the effects certain chemicals have on cheatgrass at high elevations. Clark says Colorado’s cheatgrass problem isn’t nearly as large as other western states.

“In states like Nevada, where cheatgrass has been present for so long and has been able to get ahold of that ecosystem, the problem is that if you go into those areas now, a lot of times the native plant community has been eliminated from the area,” she says.

Right now, the plant is classified as a List C noxious weed in Colorado, so it’s on the state’s radar as a potential problem. Clark says the work it would take to get all of the landowners and relevant government agencies involved in a management plan could prove difficult.

“I think that’s the biggest hurdle is just trying to bring everyone together and coming up with a strategy to start controlling it,” Clark says.

The BLM is currently studying a bacteria strain that could help control cheatgrass. In June, the Western Governors’ Association announced a partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to look for ways to address cheatgrass. Conversations are ongoing. In a statement, WGA Policy Advisor Bill Whitacre said the spread of cheatgrass has ”become a critical threat to healthy western rangelands,” adding that it harms watersheds and diminishes wildlife habitat.