That $3 you pay to ride the local bus? Or the $10.50 it costs to ride the A Line to Denver International Airport? Those costs may seem high, but collectively they don’t come close to covering what it costs the Regional Transportation District to keep its vehicles moving.

RTD brought in $143 million in revenue in 2018, according to a new staff report, against $777 million in operating costs. That amounts to a net subsidy of $634 million, much of which is covered by sales tax revenue. Factoring in depreciation, RTD calculates that fares covered just under 25 percent of what it cost the agency to provide services in 2018. According to a Federal Transit Administration analysis of 2017 data, the national average is 35 percent.

“I think all transit agencies on the planet are, pretty much, subsidized,” said board member Claudia Folska at a Sept. 17 meeting. “And I guess for us the question is, ‘How much can we afford to subsidize?’ ”

That question will likely be at the heart of the agency’s two-year process, called “Reimagine RTD,” to rethink its priorities. At the same time, RTD faces falling ridership and an impending budget crisis. The new report will help inform that effort. It shows ridership, operating expenses, and revenue from each bus, train and shuttle route in the district.

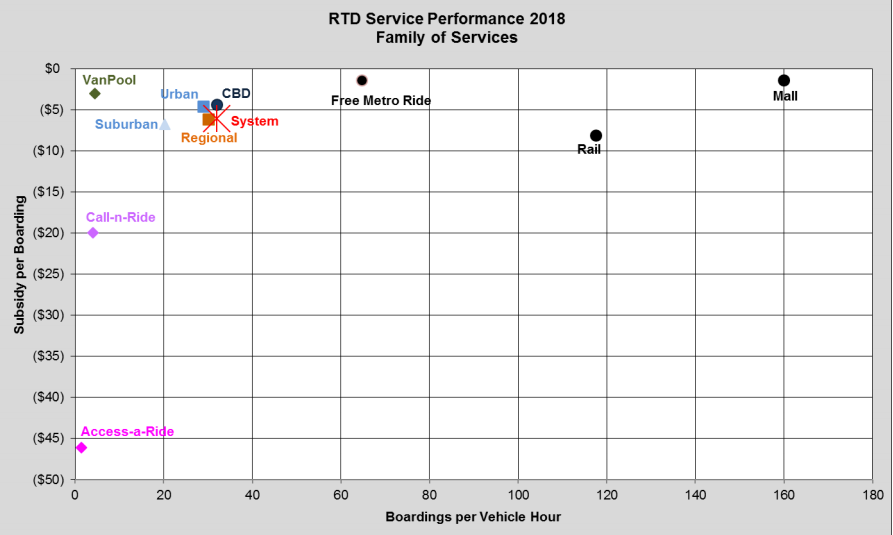

Those metrics determine how much of a sales tax subsidy each route receives — higher ridership generally means lower subsidies. Popular bus routes, like the 15 down Colfax or the free 16th Street Mall shuttle, have relatively low subsidies — $2.83 and $1.36 per boarding, respectively.

Light rail and commuter rail cost RTD significantly more, averaging about $8 per boarding. And RTD’s other services like the FlexRide, which serves low-density areas, and the Access-A-Ride for people with disabilities, have the highest subsidies.

RTD staff use the data to determine which type of service is most cost-effective for each area, and how often that service should operate.

“We connect all these services into a network,” Jeff Becker, a service development manager with RTD, told the board. “And we match the level of service to the market requirements to have financial sustainability.”

Becker said the biggest predictor of ridership in a given area is population and employment density.

“That is the main driver for transit ridership, period,” he said.

Staff judge the performance of every route against similar routes. The least productive routes of every type, based on subsidy per boarding or boardings per hour, are evaluated by staff for revisions, marketing or elimination.

RTD is somewhat limited in changes it can make to its rail network, short of limiting service as it did on the poorly performing R Line in Aurora. And it’s federally obligated to provide costly Access-A-Ride service. But it does have a lot of flexibility with bus and FlexRide routes.

Multiple board members took note of the high subsidies for FlexRide shuttles, which run from $9.87 per ride in Golden to $38.17 in Louisville.

“I just find it, for me, very disturbing,” said board member Natalie Menten. “We might as well just give these people a $5 or $8 Uber ticket.”

“These subsidies are very high and we never have enough money to do everything we need to do,” concurred board member Judy Lubow.

Becker said RTD’s FlexRide offerings, which the agency spent $10 million on in 2018, are among the most extensive of any transit agency in the country. However, he added, RTD is indeed exploring running FlexRide shuttles only during peak hours, and subsidizing taxi service during other times.

“It would save quite a bit of money and still provide the service,” he said.

Saving Money Is At The Top Of RTD’s Mind Right Now

RTD’s sketchy financial situation adds extra urgency to discussions about whether to cut high-cost service. CFO Heather McKillop told the board that sales tax revenue, which makes up the bulk of RTD’s income, is not going up much as expected.

“It's like we're living beyond our means,” observed board member Judy Lubow.

“That is correct,” McKillop replied.

The agency will have a $12 million annual shortfall each year from 2026 to 2040, McKillop said, which could require painful budget cuts.

“We're to a point that we will have to reduce service or not maintain our assets,” McKillop said, referring to the physical condition of RTD’s buses, trains and other equipment. “But it's kind of a circular argument, because if you don't maintain your assets then you can't operate service.”

RTD’s long-term plan to finish train lines promised to voters in 2004 has contributed to the shortfall. Some of the money raised through the FasTracks ballot measure — anywhere from $12 million to $20 million a year, McKillop said — was supposed to go toward bus service; today it’s being diverted by the board to help finish train lines.

“That just happens to be almost exactly what we're off,” McKillop said.

Some of those unfinished lines, like the long-sought train from Denver to Boulder and Longmont, are now decades behind schedule. RTD blames those delays on unforeseen cost increases and the Great Recession. But the criticism RTD’s received over the last decade would make it politically difficult for the agency to shift that money back to buses and prevent cuts. McKillop acknowledged that but said she wanted to present the board with the option.

“It's really hard to justify having money sitting in an account when you're having to borrow, or cut service, or not fund assets in another account,” she said.

The board will have to make a decision on how to balance its long-term budget, McKillop said. Many board members noted that the two-year “Reimagine RTD” process, which will include many meetings with the public, could give them guidance.

“It's hard. It's heart wrenching. And it is scary as hell,” said board member Angie Rivera-Malpiede. But, she said, “I think that my constituency is very interested in the fiscal sustainability and health of this agency. We need it to survive and we need it to be strong.”