George Lange held onto a box, sealed shut, for nearly four decades.

It was full of keepsakes, reminders of his friend Francesca Woodman and the good times they shared while attending the venerated Rhode Island School of Design in the ‘70s.

“She would send me prints through the mail. I kept pictures that I took of her and those negatives,” Lange said. “And also, when she left RISD, she left a ton of prints in her loft.”

Woodman was the daughter of well-known Boulder artists George and Betty Woodman. She grew up in Boulder and was an enormously talented photographer. But she died young, at age 22. It wasn’t until after her death that her artistic ingenuity was recognized and celebrated by the art world.

“After she died, for me, there was this weird feeling that if I never opened that box that [she] was alive in there,” Lange said. “And it was also so emotional around what had happened that I wasn’t ready to open the box.”

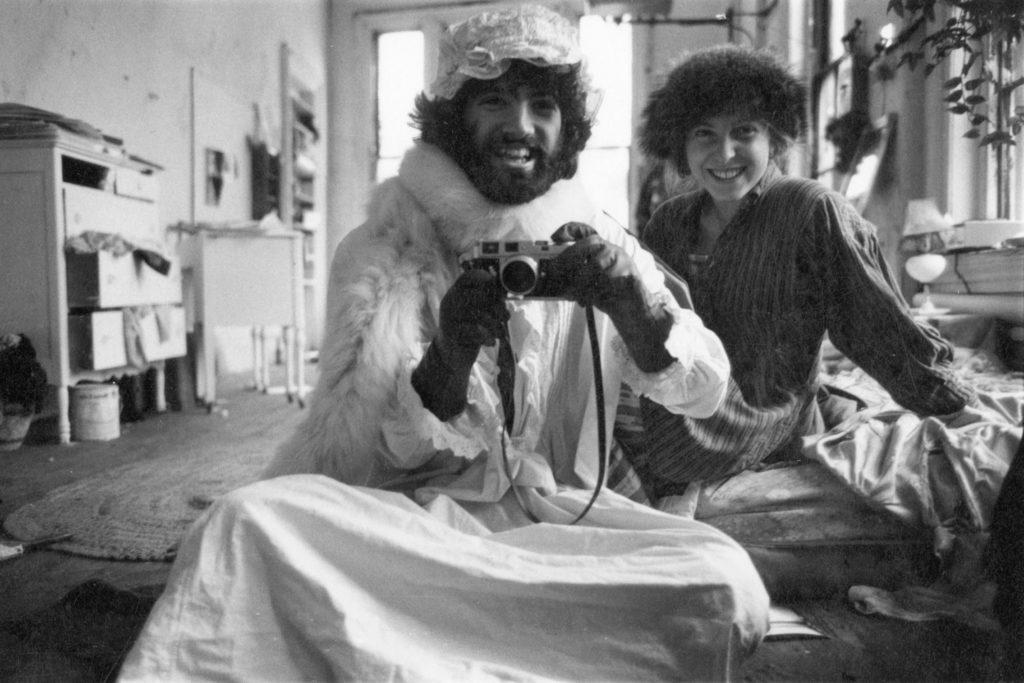

Lange, an acclaimed photographer as well, has long felt that Woodman’s death, and how she died, overshadowed her art and her life. That was, in part, what made this box “so precious” to him — it showed a very different side of his friend.

“It’s so much a part of her life that has not really been shared,” he said. “There are pictures that are probably the first pictures of her smiling and skipping around her studio, having fun and really just enjoying the process of taking pictures.”

Those prints, letters and postcards that Lange kept tucked away for so long are now the subject of a new show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

“Francesca's Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation” is on display at the museum Sept. 20, 2019 - April 5, 2020. It’s the first major museum show of her work in her home state.

Lange said he hopes the exhibition will highlight “how much fun we had.”

“She was silly,” he said, adding how she would invite him to tea or ice cream by slipping notes and “little pieces of rabbit fur” under his door.

As an artist, Woodman often pushed “against the boundaries of her medium,” said MCA Denver director and exhibition curator Nora Burnett Abrams.

“A lot of the works show her pushing her feet out of the frame or butting against the boundary of what the camera can capture,” Abrams said. “She’s trying to create a very vital and dynamic space within a medium that is fundamentally flat and stilled.”

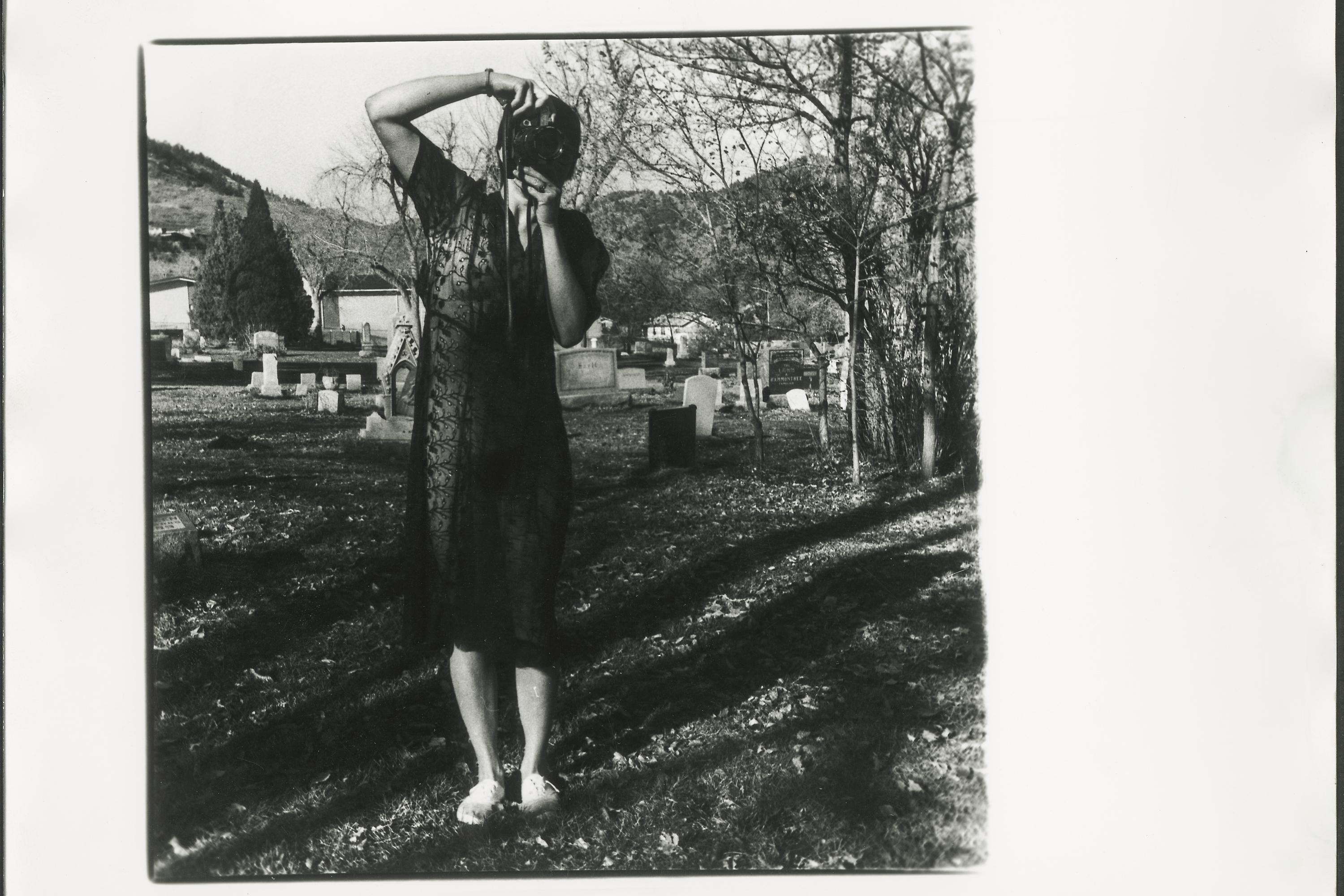

Woodman also experimented with slow shutter speeds and double exposure. Much of her work features herself, but Abrams wouldn’t describe them as self portraits.

“They’re not really coming from a place of self study,” Abrams said. “She’s really using her body like an object, an object to be pushed, and pulled, and manipulated in lots of different ways.”

The photographs show Woodman in unexpected positions, crops or settings, like a cemetery in Boulder.

“She was always working,” Abrams said. “She was always making and she was always creating. That distinction between how she was living her life and the art that she was making was completely fluid, and a lot of what we have in this exhibition really attests to that.”

When Woodman was creating, “it was an act of discovery,” Lange said.

The show tries to capture Woodman’s process of discovery, even exhibiting the work in a way that shows its imperfections, like the fixer stains or bent corners.

“It’s so much closer to the spirit of the way that [the photographs] were created,” Lange said. “Not how it’s been seen since her death.”