Six months after shouting that new legislative drilling regulations were an existential threat to their industry in Colorado, the state's oil and gas producers are now whispering a different message to Wall Street:

No big deal.

The law was billed by both supporters and opponents as a sea change in how the industry is policed, giving local governments and state agencies greater authority to decide where and how drilling can occur. But in filings with the federal Security and Exchange Commission, some of Colorado’s largest drillers now express confidence that they can easily navigate the regulations spinning out of Senate Bill 19-181.

“We do not foresee significant changes to our development plans, as we have all necessary approvals of more than 550 permits to drill wells over the next several years,” Noble Energy representatives wrote to investors.

And Noble wasn’t alone in that assessment.

In their own filing, PDC Energy officials said much the same. “We ... have approved permits for development through a significant portion of 2020.”

As did Extraction Oil & Gas: “Although industry trade associations opposed SB 181, management believes that Extraction can continue to successfully operate our business.”

The confidence only extends so far. Most of the biggest oil and gas companies operating in Colorado offered a caveat that things are fine — for now. The rulemaking process around SB 181 is really just getting started at both at the state and local level.

Anadarko Petroleum, recently purchased by Occidental Petroleum, echoed the other companies when it warned of “additional disruptions in operations that may occur as the Company complies with regulatory orders or other state or local changes in laws or regulations in Colorado.”

The Extraction Example

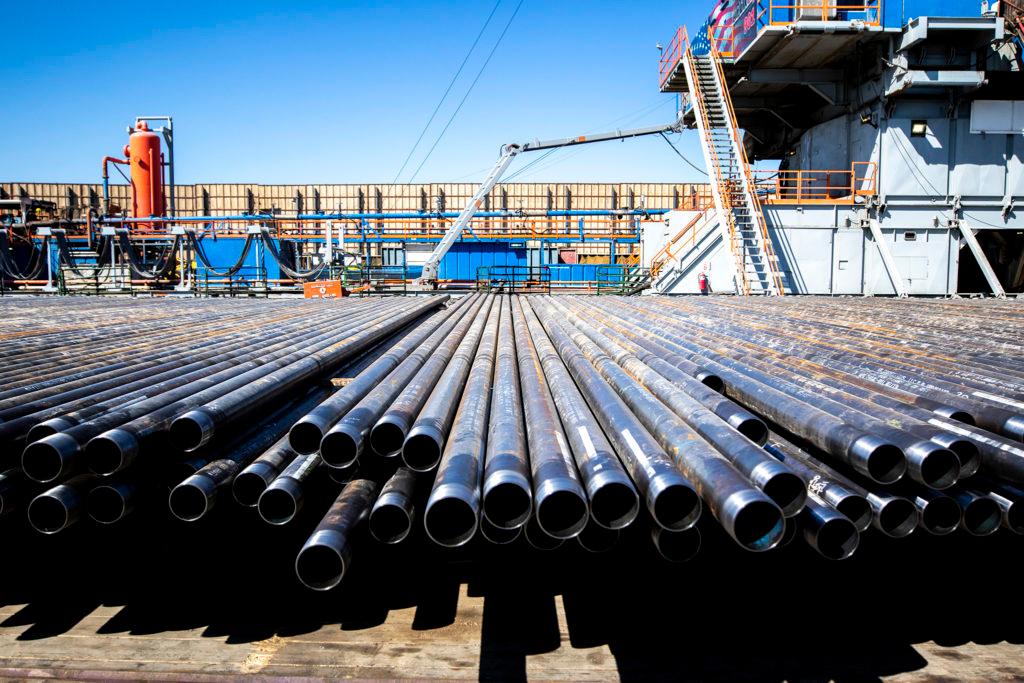

Few Colorado drillers are as open about allowing a reporter to visit a drill site as Extraction Oil & Gas, a Denver-based company. In Broomfield, their operations are quiet enough to allow an interview to be conducted next to an operating drill rig.

“The fact that you’re not hearing a lot of really loud diesel noise right now is something that we’re very proud of,” said Brian Cain, spokesman for Extraction. “We were among the first to bring electric rigs to Colorado and to this basin.”

Standing next to the rig, you can’t help but be in awe of its size. And it’s easy to see why many in the nearby sprawling suburban neighborhood were not happy to see it go up. This is probably the most controversial operation in Colorado.

The company contends though that this is among the cleanest drilling operations of its kind, and they believe it’s the future of drilling here.

“You know, I think Colorado’s changing, Colorado changed with SB 181,” Cain said.

Essentially, Cain said, he thinks their operation is already prepared to comply with any new rules the state or counties can throw at them.

What is SB 181?

The new law gave local governments new authority over surface impacts and rig and well location. Adding new powers to communities, some of which are filled with citizens and politicians deeply opposed to oil and gas, is a big shift for the industry to navigate. (Though, most drilling is located in Weld County, and local leaders there have gone out of their way to welcome the development.)

But 181 also gave the state regulator, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, a new mission to prioritize public health, the environment, and safety. Gone is language about fostering, “the responsible, balanced, development and production and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas…”

COGCC staff have proposed “over 160 suggestions to change current rules and propose new rules” to conform the agency to the new mission, according to a staff presentation in August. The rules span everything from reducing truck traffic to reforming spill reporting and flowline mapping all the way to increasing “community engagement in the permitting process.”

COGCC hearings are scheduled through the summer of 2020.

There are Winners and Losers

As SB 181 made its way through the legislature, the oil and gas industry attacked it at every turn. On TV, ads from the American Petroleum Institute charged that lawmakers were trying to “pass a law in the middle of the night, to shut down energy production in Colorado.”

While much is still in flux with the new regulations, it’s clear that it won’t shut down energy production anytime soon. Colorado is on pace to again post record oil output in 2019, 91 million barrels through June, 12 percent over the previous year’s record production.

Oil and gas production is increasingly dominated by just a few large players. While 190 companies report pumping oil in 2019, the top eight operators account for 81 percent of the production.

Large companies are changing their approach in Colorado, recognizing it won’t be drilling technology leading to improved production that sets them apart, said Michael Orlando, an economist with Econ One Research who consults with local energy companies and lectures in the Global Energy Management Program at the University of Colorado Denver.

“The thing that differentiates companies is how sophisticated are they in dealing with the social reality that they live and work in,” Orlando said.

Responding to that social reality may mean lots of community engagement, altering drilling plans and adding cleaner, quieter technology, like Extraction has done on its Broomfield site. But Orlando agrees that all costs more money, and he said the bigger companies can better spread the impact of that cost.

“If you don’t have a large organization over which to spread it, it could be the decisive factor,” Orlando said.

PetroShare, a small oil and gas driller that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in early September, blamed the new regulations in Colorado.

"Unfortunately, the collateral damage of Senate Bill 181 has manifested itself in the slowdown of the state's oil and gas sector, resulting in job losses,” said Stephen J. Foley, CEO of PetroShare, in a news release announcing the bankruptcy.

Employment in the Mining and Logging industry, however, has remained stable throughout the year in Colorado.

At a conference in late August put on by the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, Gov. Jared Polis threw cold water on the idea that state or local regulations would substantially harm the industry.

“We don’t have the power to move markets,” Polis told the room of drillers. He said the industry is more driven by the price of oil then by new regulations. “It has nothing to do with me, nothing to do with our state politics and less even to do with national politics. It really has to do with supply and demand.”

Bernadette Johnson, an energy analyst for Enverus, said there’s no doubt the regulations have a financial impact. But, “I think the bigger implication for bankruptcies and those types of things, is just the quality of your resource. Are you in a good area with good rock?”

PetroShare didn’t respond to a request for comment.

It is true that Wall Street has cut off what once was free-flowing capital for oil and gas, and investors aren’t wasting time with marginal drillers anymore. Oil and gas companies have struggled in the new paradigm across the globe, not just in Colorado.

The Oil and Gas Wars Are Not Over

Back in Broomfield, even as Extraction Oil & Gas touts its ability to drill with minimal impact and comply with new regulations, there are still bitter fights on the horizon. Residents near the well, have filed more than 200 complaints with the city of Broomfield, for noise, traffic and odor.

“We had our windows open one night, we turned our whole house fan on,” recalled Mackenzie Carignan, who lives a quarter-mile from the well. “And the fumes that came into my house were gagging my children in their beds.”

Air monitors, run by Colorado State University and a third party contractor for the city of Broomfield, show very small increases in emissions during drilling — emissions that are well below health standards. The air quality reports draw a link between drilling operations and when odor complaints spiked.

“The really horrifying thing for me, is that this thing exists in the middle of my neighborhood,” said Carignan, who is part of a group of residents organized against Extraction’s Broomfield operation.

On the final Sunday in September, protesters gathered near Extraction’s highly prized operation and called for its removal and the end of all similar rigs anywhere in the state.

It perfectly illustrated the risk of operating in Colorado’s urban areas. Drillers believe they can work with communities, and even thrive under Senate Bill 19-181 and tough new regulations.

But many of those who live near the rigs won’t stop fighting until they’re gone for good.