Since voters approved a multi-billion dollar capital plan called FasTracks in 2004, the Regional Transportation District’s expansion efforts have been nearly all about trains — they’ve opened the four new rail lines since 2014, and there are plans for another next year.

Now though, the transit agency is exploring a new network that could have the speed of rail with much cheaper costs.

Yes, RTD is looking to get back on the bus.

Not just any old bus, though. RTD is putting the finishing touches on a study of busy arterial roads that are good candidates for bus rapid transit. Those lines would use rubber on pavement and have other premium characteristics that are more typical of rail. The most important are dedicated lanes so buses run independently of traffic and service as frequent as every five minutes.

The popular FlatironFlyer is a bus rapid transit-like route between Denver and Boulder. Separately, RTD is studying another route from Boulder to Longmont. Other cities, like Minneapolis, have launched their own fledgling bus rapid transit networks in recent years.

Perhaps most importantly, the idea is for these buses to appeal to people who aren’t currently riding. They’re designed in a way, said Brian Welch, RTD’s senior manager for planning technical services, that signals to riders that the lines are different.

“They can tell by the vehicle,” he said. “They can tell by the station. And they know that it's going to be frequent and reliable and fast.”

RTD sees faster buses as a way to move more people through dense corridors in a more cost-effective way than building trains, Welch said. Boosting ridership is a top concern for RTD, which is facing financial headwinds as it tries to simultaneously finish billions of dollars’ worth of unfinished train projects. But the plan could prove unpopular with the thousands of motorists who would likely be forced into fewer lanes — unless they decide to get on the bus.

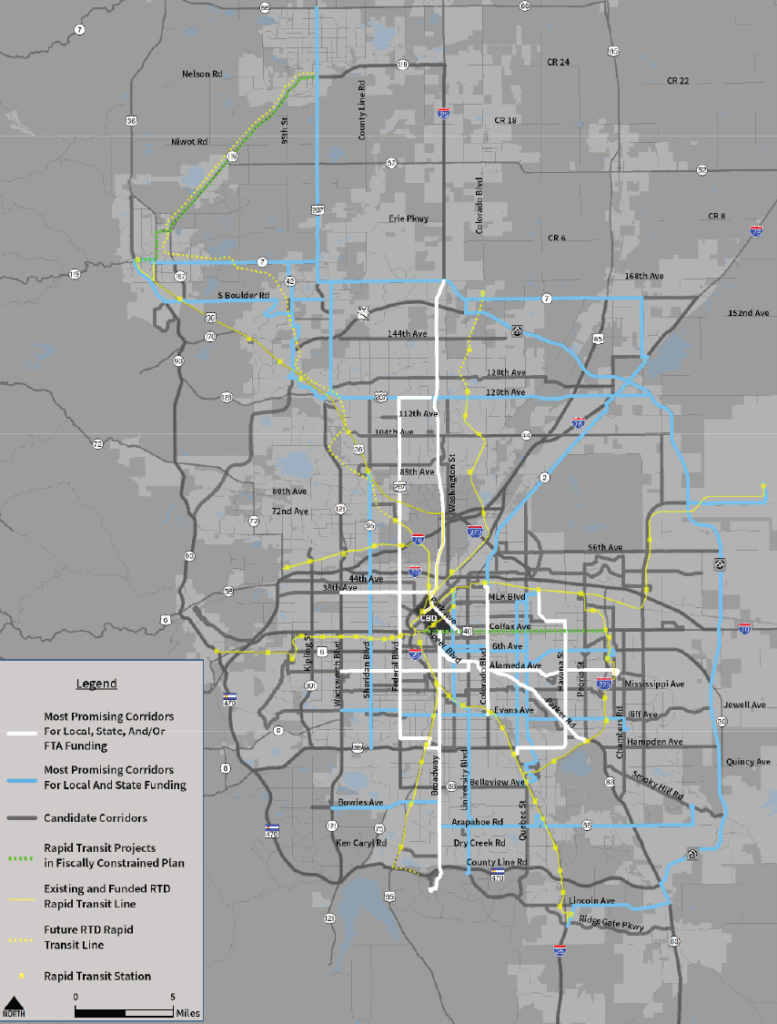

The most suitable corridors are mostly in and around the urban core.

RTD’s feasibility study started with 30 or so corridors from Longmont in the north to Parker in the south. That’s since been winnowed down to eight: I-25 north of Denver, Park Avenue/38th Avenue, Speer Boulevard/Leetsdale Drive/Parker Road, Broadway/Lincoln Street, Colorado Boulevard, Alameda Avenue, Havana Street/Hampden Avenue, and Federal Boulevard.

Estimated capital costs for those range from $25 million to $80 million, with costs per mile of about $4 million. The most popular routes could carry more than 13,000 passengers a day by 2040.

In contrast, RTD has spent more than $5.6 billion on FasTracks trains and supporting infrastructure since 2004. The four lines that were open by 2018 combined to carry about 38,000 passengers a day. The G Line to Arvada opened since then, and the N Line to Thornton should open next year.

Those rail projects took decades of planning and construction work, and could see ridership increase as development fills in around stations. But the impact of bus rapid transit lines down corridors like Federal could be felt far faster, Welch said, because they already cut through dense residential and commercial areas.

“We know that we'll have to make decisions that involve resources where you're choosing between A and B,” Welch said. “The future is to provide as much service throughout the district as possible at the best cost. And bus rapid transit has proven to be, around the United States and globally, a very good solution.”

But losing a lane of traffic is a tough proposition for people who use those streets every day. Saul Lopez, a house painter from Denver, said he often carried his materials in his van up and down Federal.

“You can't really do that on a bus,” he observed from a gas station parking lot.

Eric Molina, a college student from southwest Denver, said he’s seen traffic on Federal get worse and worse in recent years. He’d rather Federal stay completely open to cars, though he’s open to change if it’s more efficient.

“I used to take the bus to school. I've seen some crazy stuff happen on the bus so I try to avoid it,” he said. “But if I need to, I'll take it.”

There’s no set timeline for any of these projects.

RTD will wrap up its study in late 2019 and then start applying for federal grants. In order to take over traffic lanes, it’ll also need buy-in from local governments, or in the case of state highways like Federal Boulevard, the state of Colorado.

RTD said some cities like Westminster and Broomfield are very supportive, while others like Greenwood Village are less so. In a statement, CDOT Executive Director Shoshana Lew did not commit to handing over any lanes. But she called bus rapid transit an “effective option for providing efficient access along key corridors.”

“We look forward to seeing the results of RTD’s study, especially as it relates to putting ideas on the table for improving transit reliability on urban arterials roads in metro Denver that are within CDOT’s purview,” she said.

The other big fish is Denver. And as that car-centric city grows and densifies, it appears it’s ready to play ball.

“We have a finite system that has a limited amount of capacity and we can only move a certain amount of people,” said Ryan Billings, transit and corridors planning supervisor at Denver Public Works. “People movement is really the crux of the conversation.”

Billings cautioned that the city will need to do a variety of studies on each corridor before any major changes are made, though he said Denver is generally supportive of RTD’s plan for faster buses. It’s also moving forward on its own plan for BRT along Colfax Avenue. There’s a need now, he said, and it’s only going to get more pressing over time.

“I can either beat my head against the steering wheel in that traffic in 10 years,” he said. “Or I can make a decision, or a choice to, potentially get on that bus in that dedicated lane and get there a little bit quicker.”