Updated 2:32 p.m.

More than 160 Colorado children were sexually victimized by 43 priests over 70 years — and Colorado’s three Roman Catholic dioceses spent decades trying to cover up that abuse, according to a special report released by the Colorado Attorney General’s office Wednesday.

Though all of the incidents of abuse examined in the report happened 20 years ago or longer, the report offers no exoneration to today’s church leadership. On the contrary, the report warns that record keeping and reporting processes are still lacking, making it impossible to conclude that children are now safe around priests.

“Arguably, the most urgent question asked of our work is this: are there Colorado priests currently in ministry who have been credibly accused of sexually abusing children?” the report said. “The direct answer is only partially satisfying: we know of none but we also know we cannot be positive there are none.”

The comprehensive investigation into the state’s three dioceses, Denver, Colorado Springs and Pueblo, took months of work by investigators led by Colorado’s former U.S. Attorney Bob Troyer.

Troyer resigned from that post a year ago and was appointed the special master of the church investigation in February.

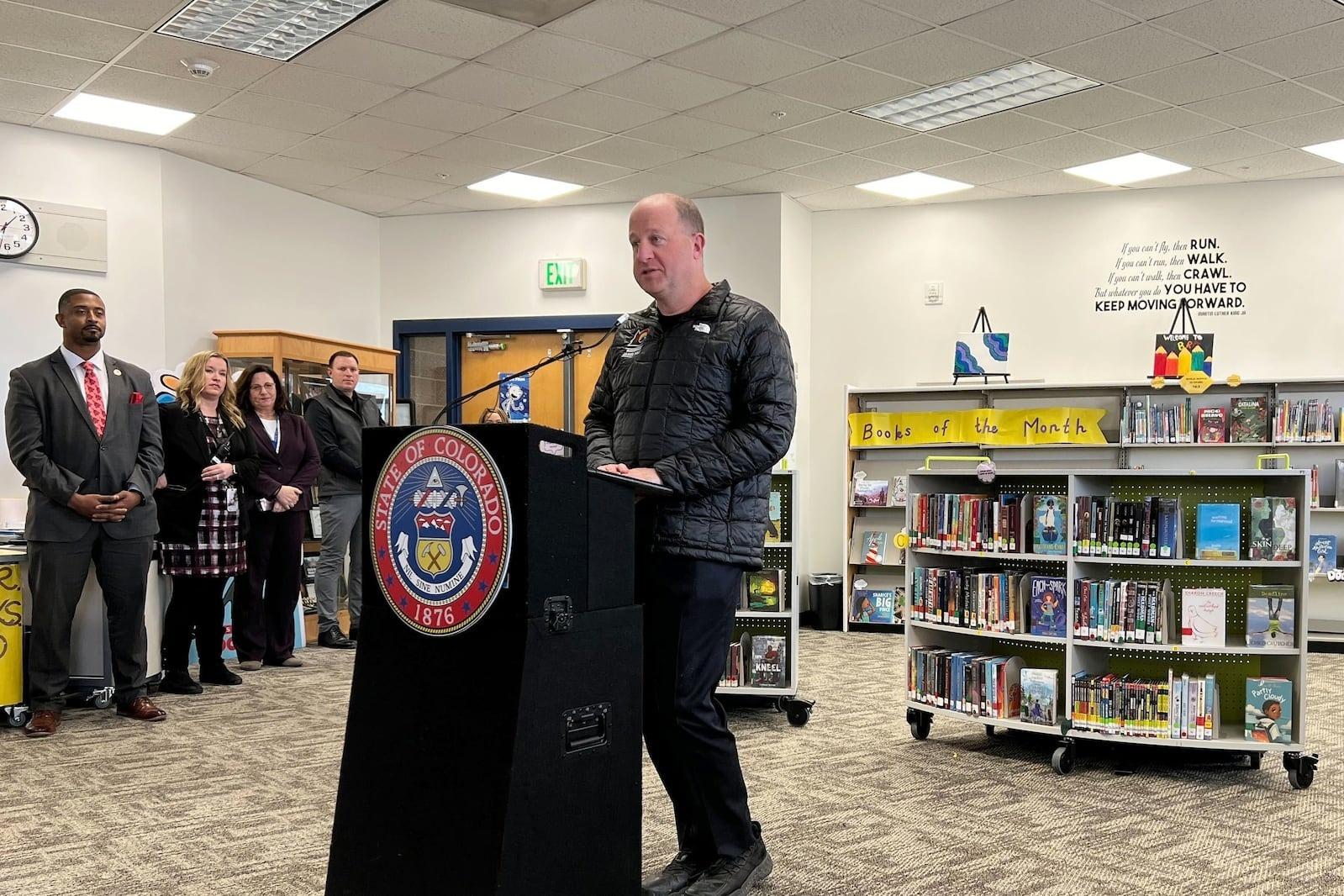

Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser, who commissioned the report, said he was disturbed by the findings.

“It’s unimaginable,” Weiser said. “The most painful part for me, we’ve had stories told of victims coming forward and they weren’t supported ... I think the church should do better.”

In a letter to Denver Catholics released at the same time as Troyer’s report, Denver Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila pledged to meet with any survivor of abuse who wanted to speak with him.

“I know there are no words that I can say that will take away the pain. However, I want to be clear that on behalf of myself and the Church, I apologize for the pain and hurt that this abuse has caused, and for anytime the Church’s leaders failed to prevent it from happening,” Aquila wrote. “I am sorry about this horrible history — but it is my promise to continue doing everything I can so it never happens again. My sincere hope is that this report provides some small measure of justice and healing.”

Troyer had access to hundreds of records and conducted interviews with dozens of people about child abuse in the church over 70 years. The church voluntarily opened up hundreds of files — including what the church calls its “secret archive” which are files where leaders squirreled away the documentation of abuse church leadership called “bad enough that we need to hide it … the worst type of stuff.”

The report explicitly details the incidents of abuse and names the priests responsible. But it also only looked at the abuse of children by priests who were hired by and worked in Catholic diocesesan-run churches in the state - not those priests from religious orders who worked in Colorado parishes.

“It is also important to understand what this Report does not include, per the Agreement. It does not chronicle abuse committed by religious-order priests in Colorado or by Diocesan Priests before they were ordained,” the report noted. “It does not report clergy sexual misconduct with adults, including adult Church personnel like religious sisters or adult seminary students.”

Still, the report uncovered allegations of abuse against some of the state’s most prominent Catholic clerics. Among them, Msgr. James Rasby, who co-founded Samaritan House homeless shelter in Denver, and was longtime director of the Cathedral Basilica. He was accused of abusing teen boys in separate incidents in 1975 and 1990. After the second incident, the archdiocese required him to attend regular counseling but took no steps to prevent him from being around children or monitoring him in any way, according to the report.

Another accused priest, Msgr. Lawrence St. Peter, rose to become the archdiocese’s superintendent of schools despite allegations of abuse dating back to the 1960s. The report found that St. Peter’s church file had been sanitized of the details of complaints against him.

“It was widely rumored that St. Peter used that access to destroy incriminating documents in his own files,” the report said. “To be clear, though, we found no witness or document directly proving that. Instead what we found is strong circumstantial evidence.”

Troyer and his team of investigators were sharply critical of the church and how slow it was to respond to abuse allegations and to problem priests. Investigators found that the amount of time between a credible allegation of abuse leveled against a priest and a church restriction on that priest interacting with children averaged 19.5 years during the period examined.

“Concluding from this report that clergy child sex abuse is 'solved' is inaccurate and will only lead to complacency, which will in turn put more children at risk of sexual abuse,” the report said. “Our review revealed flaws in the Colorado Dioceses’ records and practices that make it impossible to honestly and reliably conclude that no clergy child sex abuse has occurred in Colorado since 1998 — or that no Colorado Roman Catholic priests in active ministry have sexually abused children or are sexually abusing them.”

Among other findings:

- For decades, Colorado churches employed euphemisms to shroud reports of child abuse, calling anal rape of a 12-year-old boy a “boundary violation” and a serial abuser priest plagued with “boy troubles.”

- The church still maintains paper files of all their priests and a priest’s file often will not contain information relevant to that priest’s sexual abuse of children.

- More than 50 percent of sex abuse victims were abused after the relevant diocese was aware that these priests were abusers.

- The most recent clergy child sex abuse — that victims have reported and that Colorado’s Dioceses have recorded in their files — occurred when a Denver priest sexually abused 4 children in 1998. Over two-thirds of Colorado’s 166 child victims were sexually abused during the 1960s and 1970s. Priests abused 9 children in the 1980s and at least 11 children in the 1990s.

But the report also notes that credible allegations of abuse from the 1960s and 1970s continue to flow into the church.

“The Denver Archdiocese and the Pueblo Diocese have received more reports of past abuse in 2019 than they had collectively received in 5 prior years,” the report notes. “And Colorado’s Dioceses collectively averaged 4 clergy child sex abuse allegations per year even from 2017 to 2019. But the abuse itself that has been so recently reported actually occurred in the 1960s and early 1970s.”

The report outlines several detailed recommendations to the dioceses to strengthen both record-keeping and the response to any future reports of abuse. Among them:

- Hire an independent investigative group to handle clergy abuse complaints.

- Develop an electronic record-keeping and tracking system to manage records of complaints.

- Hire a victim assistance coordinator with the sole job of providing victim care.

- Create a “see something, say something” culture within the church.

- Hire an outside auditor to review church reporting and response systems at least every other year.

In his letter to parishioners, Aquila said the Denver Archdiocese would follow Troyer’s recommendations.

“Indeed, we will follow all of Mr. Troyer’s recommendations and are already working to implement changes,” Aquila wrote. “I plan to personally be involved in that effort and will be in continued contact with Mr. Troyer and the Attorney General to make sure our collaboration to protect children is ongoing.”

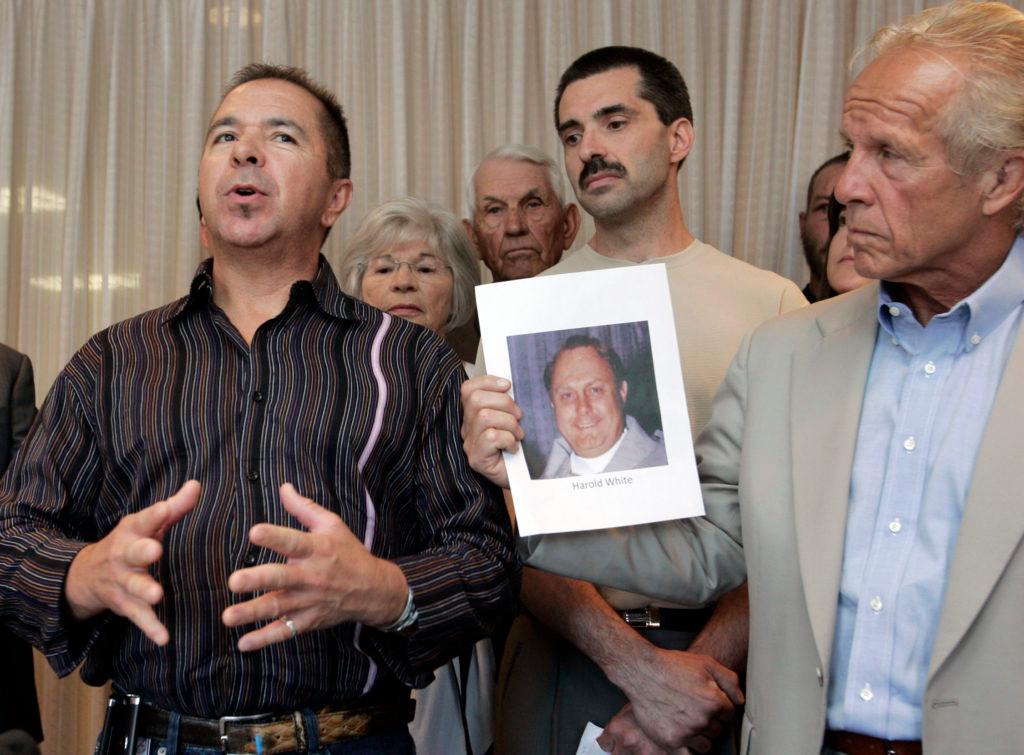

As was previously known, the report found that Harold Robert White, a defrocked priest who worked across Colorado for decades, was the state’s most prolific abuser.

But the new report exposed White’s decades-long record in greater and more disturbing detail than ever, saying it was “more likely than not” that he had sexually abused at least 63 children starting around 1960. The report found he groomed victims for abuse by buying them alcohol and taking them on trips; forcibly fondled children; forced a girl to violate herself with a ruler; and engaged children in masturbation.

Officials at the Archdiocese of Denver knew of accusations against White throughout his 33-year career, according to church files previously released by Jeffrey Anderson, an attorney who has represented some of White’s accusers.

In 1961, a boy reported that White solicited him for an “unnatural act.” In the years to come, church officials recorded at least four more reports of concerns or allegations about White. Eventually, dozens of people would step forward to say that White had abused them.

Church officials followed a pattern that would become familiar across countless global cases. In the 1961 accusation, one described a “first attempt” at abuse and guessed there was “no danger” of a scandal. And they looked for a “cure” to White’s apparent pedophilia and abuse, according to letters in his file.

When White admitted to improperly touching several boys, officials decided that he had to “leave the (Denver) parish immediately … because of the wide knowledge of his offenses.” He was transferred to Colorado Springs, but by 1965 officials already were moving him out for so-called “boy troubles.”

In 1981, after several more accusations and complaints, White took a “healing” sabbatical before returning to work. His career continued for years afterward, including stops in Sterling, Loveland, Minturn, Eagle, Vail, Aspen and Steamboat Springs, according to a dossier compiled by BishopAccountability.org and based on church directories.

The report found that it was “more likely than not” that White abused at least 63 children over his career.

Brandon Trask, 63, of Long Beach, California, reported that White raped him in a Minturn, Colorado parish in the early 1970s. He eventually received a $250,000 settlement from the church.

“I think the archdiocese should be forced to get counseling to everybody, that would be parents, siblings and the victim ... It changed me,” Trask said, this week.

Trask, who heard about Weiser’s investigation through his lawyer, said he hopes the church keeps good records of the abuse. After he broke his silence about White’s abuse, more than 40 other victims came forward. When Trask requested the official investigation report from the archdiocese, he said he didn’t see his own name in there.

“The record-keeping,” he said. “I hope they keep better documentation.”

White died of an apparent heart attack in 2006, not long after the accusations first surfaced publicly. By 2008, the Archdiocese of Denver had settled 43 lawsuits involving White and two other priests, Leonard Abercrombie and Lawrence St. Peter, for a total of more than $8.2 million, according to The New York Times.

Attorneys for abuse survivors warned that the report didn't capture the full picture.

"As shocking as this information is, it's also a half-truth, because the other half of the truth is yet to be revealed because it's still concealed by the Catholic bishops," said Jeff Anderson, who has represented abuse victims since the 1980s.

He wants to see Colorado rewrite its statute of limitations to allow lawsuits and prosecutors pry open more cases. Despite covering dozens of priests, the AG's report did not result in any referrals to prosecutors. Authorities already were aware of the single eligible case.

Adam Horowitz, who also has handled Colorado church abuse cases, said that the review was limited by its cooperative nature.

"That is an enormous number by any stretch. But when you consider how the data itself was assembled, it's really, really alarming. And that's because the attorney general allowed the church to self-report. They didn't use subpoena power, they didn't use search warrants. They relied on the diocese and their legal team to manually review each paper file and decide for itself what to report," he said.

"So, it goes without saying, that the data is only as good as the integrity of the institution that is self-reporting."

The true number of victims could be 500 or more, he estimated.

At the same time that Weiser appointed Troyer to lead the investigation, he launched an independent reparations program that allows child abuse victims to apply for claims.

That program, administered by Kenneth Feinberg, started to accept applications in early October. It is the second time the Denver Archdiocese launched a reparations program.

Weiser said he considered the investigation and the release of the report to be a beginning step toward improving the protection of parishioners and the response to victims.

“If we can set this example in Colorado, this is a national challenge,” he said. “My job is to support victims who have been hurt, providing compensation and calling out wrongdoing.”