Ok.

It’s a simple enough affirmative response to something — or it used to be. But if one teenager texted that one-word sentence, period included, to another teenager, it’d be fighting words.

The OK, period, means you’re mad. The most neutral affirmative response would be “ok” — and that’s it. There’s also “ok!” “okkkkkk” or “ok…”

When your social life relies on texting and social media, punctuation is everything. Add in timing — the modern versions of rules like “wait three days to call him” — and emoji, which do more work than you might think, and you’ve got a whole new way of communicating.

And it’s not just a teen thing. While there’s some fear amongst older generations that Generation Z isn’t really communicating, effective communication via text is everyone’s problem — and teens might be better at it.

As Kira Hall, a professor of linguistics at the University of Colorado Boulder, points out, 96 percent of American adults have cell phones and 81 percent have smart phones. Cell phone use is ubiquitous.

“It is communication,” she said. “ There’s no going back.”

I’m mad. Period.

The period, in the digital age, has found enormous power. Its presence or absence completely changes the tone of a text.

“Thanks” vs. “Thanks.”

“No” vs. “No.”

“It’s fine” vs. “It’s fine.”

Hall teaches a class called Language and Digital Media in which she and her 20 undergraduate students explore ways in which people communicate in texts and online. And in that class, the period is a favorite topic.

No longer a mere signal for the end of a thought, the period carries emotional weight.

“The default would be no period, so if there is a period, you need to read meaning into it,” she said. “It comes across as this kind of forward punctuation mark that must have meaning.”

Clarise, 15, said a period at the end of a text is a cause to “really read into things.”

“When people punctuate texts — like my dad would be like, ‘OK,’ period. And I'm like, ‘Oh my God,’ reading into it,” she said.

In 2013, a New Republic piece sparked a popular discussion about the period as a passive-aggressive punctuation mark, Hall recalled.

In the story, editor Ben Crair wrote:

"This is an unlikely heel turn in linguistics. In most written language, the period is a neutral way to mark a pause or complete a thought; but digital communications are turning it into something more aggressive. 'Not long ago, my 17-year-old son noted that many of my texts to him seemed excessively assertive or even harsh, because I routinely used a period at the end,' Mark Liberman, a professor of linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, told me by email. How and why did the period get so pissed off? It might be feeling rejected. On text and instant message, punctuation marks have largely been replaced by the line break."

In 2015, scholars gave sample sentences to 126 undergraduates — texts with periods and texts without periods — and the students generally thought texts ending with periods were more insincere. They felt a person who texted “That’s fine” really meant it and a person who texted “That’s fine.” did not.

Conversely, another study looking at longer text messages regarding emotional issues found that young people do use periods in those cases — specifically to indicate sincerity and the emotional weight of the subject, Hall said.

There’s also the period’s versatile cousin, the ellipsis. Deployed at the end of a short sentence, it can be nerve-wracking or devastating. “Thanks…” your teacher or boss might say when you’ve turned in work. “This is good…” he might say later, unaware that his ellipsis habit is making people worry that he’s always disappointed. “Ok…” he will say when you tell him that, correctly using the ellipsis to indicate his skepticism or uncertainty.

Or maybe, sarcasm.

Don’t you just ~*love*~ sarcasm?

Here’s a sarcastic sentence:

Wow super cool that my bus 10 minutes late it’s great I love it...

There are three elements signaling sarcasm: Ellipses, over-emphasis of how great it is, and the omission of punctuation for a run-on thought that indicates a deadpan tone.

Here’s another one:

Just ~*love*~ when I remember a paper two hours before it’s due.

Pretty self-explanatory — and the closest the English language has come to actually having some kind of punctuation to indicate sarcasm. It’s been suggested before, but it hasn’t stuck.

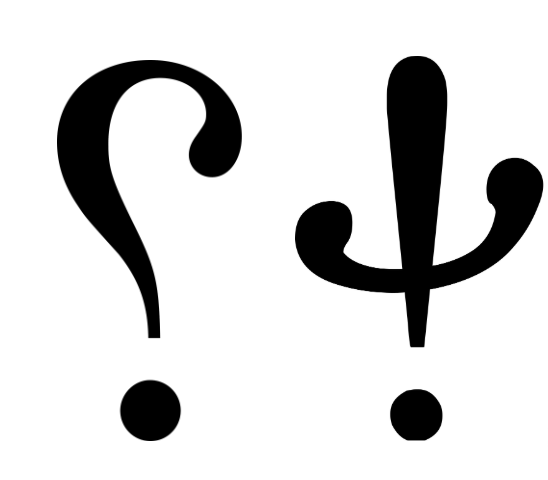

One very early and notable attempt at a sarcasm punctuation mark — also known as an irony mark —was by John Wilkins in 1668. The character he suggested looked like an upside-down exclamation point. Hall tells his story in her class.

“Sarcasm is a really important one, right? Because if you type something meaning sarcasm and it’s not read meaning that, you could get yourself into a lot of trouble,” she said.

There were a few other attempts at the irony mark over the centuries. One was a backward question mark, another was the Greek letter ψ with a dot below. Both were proposed by French writers — poet Marcel Bernhardt (aka Alcanter de Brahm) in 1899 and author Hervé Bazin in 1966.

But in 2019, teens (and the rest of us) have a variety of ways to show sarcasm. Students in Hall’s class use some of the more relatively subtle techniques already mentioned, but they also have more overt methods.

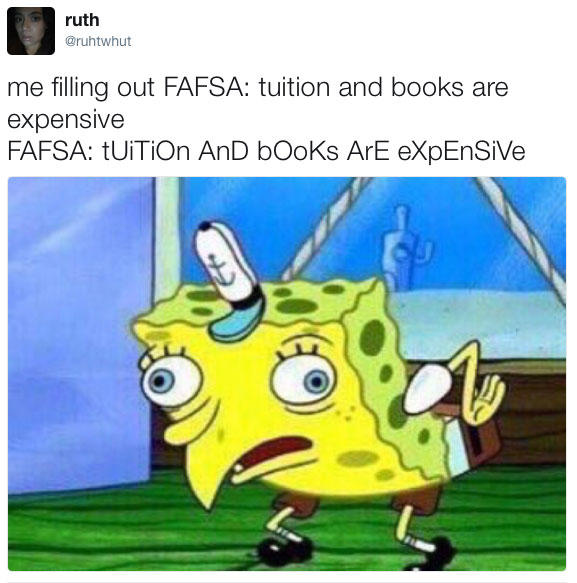

“How people represent it online shifts over the generations,” Hall said. “The main thing they do now — all 20 students in the class — is inspired by a Spongebob meme, where you capitalize every other letter or you start with small caps and then you capitalize.”

“They’re also using other things, too — using what a previous generation might think of as an ellipsis, a dot dot dot,” Hall said. “Other people use, to show sarcasm, an emoji that has the eyes rolling upwards, or maybe what looks like an elongation pronunciation, with a repetition of the vowels.”

So, if you really wanted to be clear about your sarcasm, you might go with an “okkkkkkkk… ?”

Emoji as gesture

Some of the visual cues we lose in digital conversation are, unsurprisingly, easily replaced by those tiny, emotive pictures we call emoji.

Let’s go back to the example of “ok.” Here are a few ways you might use it in a text:

Ok ??

Ok ?

Ok ??

Ok ?

Ok ?

In order, those indicate general agreement, irritated or sarcastic agreement, enthusiastic agreement, cute or affectionate agreement and — this is somewhat advanced — not-thrilled-but-smiling-through-it agreement.

This is how emoji act as gesture, as linguist Gretchen McCulloch puts it. They’re replacing body language, though not always precisely replicating it.

Sometimes, too, they’re there for emphasis:

?LIZZO THE GREATEST OF ALL TIME

Or

Your girlfriend is not ?? your ?? mom ??

Or they’re used for a little flourish:

Who’s coming out tonight?? ?? ?? ??

Or

Happy birthday! ???

Most importantly, they are almost never used to actually replace words, as many people once feared. Emoji sentences are largely a fiction. There was definitely a moment in which people were trying to make that a thing, but it didn’t stick.

It all changes so fast, but there’s no reason to panic.

Moral panic about the way young people communicate in texts and online started in the early 2000s, Hall said. But what we have and what we’re still developing isn’t a new language, it’s just our usual language adapted to modern life.

What sets these changes apart from past evolutions in language is the rate at which they’re happening, and the fact that that rate is accelerating, thanks to the number of people contributing — and to the global scale of the change.

“What’s so unique about what’s happening now is it’s broken down so the whole mass of people are contributing to language change,” as opposed to just scholars and prominent writers, Hall said. “It’s a participatory contribution. It’s not from the top down as it was in the past.”

That means that now more than ever, teenagers are driving language change. It also means that the way teens communicate is more visible to adults — it’s not just in person and in texts, it’s all over the internet — and its prominence in our culture creates more waves, more fear.

“I think even now what I see happening is it’s no longer the moral panic,” Hall said. “It’s more about a fear that our kids aren’t learning literacy, they don’t know how to use standard language and punctuate and spell. And a fear that they’re socially backward, that they’re kind of hiding from social life.”

“I think on both accounts the literature really shows something a lot more complex. Young people are writing now more than ever before,” Hall continued. “They’re writing all the time. I think they have a really good sense of what a text message is versus an email you send to you professor versus a blog post you want to sound intelligent. They know how to code-switch between formality and informality.”

Jonah, 18, said he texts differently with his adult coworkers.

“If I need to ask someone to cover my shift, it's not like, ‘Hey, yo, cover my shift please?’” he said.

And with his parents and grandma, too, Jonah uses standard punctuation and complete sentences — and definitely less slang. It comes naturally to him, as it does to most teenagers.

Put briefly: They’re fine ???

We want to know more, and we hope you do, too.

CPR News will spend the next few months investigating the factors that have created the ultimate pressure cooker for some teens. We’ll go into their world through audio diaries, interviews, reflection and analysis. Most importantly, we’ll examine what teens, families and schools can do to let some of the pressure loose.

_