An extraordinary discovery in the backyard of Colorado Springs has created a window into an evolutionary period we previously knew very little about.

Microscopes, plaster casts, and the sound of small drilling machines fill the fossil labs at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Vertebrate paleontologist Tyler Lyson picks up a bowling ball-sized rock and points to the fossilized bones embedded in one side of it.

“This is one of several crocodiles that we found at Corral Bluffs,” Lyson says.

Corral Bluffs is a windswept rocky outcropping just about 15 miles east of Colorado Springs. Lyson describes it as “just this series of these mud stones and giant sandstone types of rock. Maybe 120 feet that rise into the air.”

On a fall day back in 2016, Lyson was out there with his colleague Ian Miller, a paleobotanist who specializes in plant fossils. The two of them were trying to solve one of the biggest puzzles of evolution: What was life like after the extinction of the dinosaurs?

Miller says we know that a mega-asteroid hit the earth 66 million years ago, killing off the dinosaurs along with most of the species on the planet. But how life on earth then rebounded has largely remained a mystery.

"Nobody really had a great view into that world because we just didn't have the data. We didn't have the fossils." - Ian Miller

That was about to change when Lyson examined a rock that day at Corral Bluffs.

He had a tip from a museum volunteer who had found a jaw bone fossil out here encased inside a rock-like formation called a concretion.

“He picked one up, broke it open,” Miller recalls. “And you could see both sides of a mammal skull on either side sort of staring back at him. And I can remember he just sat down and started laughing. Looking at us, like, ‘Oh, my God, like, is this really happening?’”

Within the next half hour or so, Miller says, they found five intact skulls – all from previously undiscovered species. They knew right then that they’d hit it big.

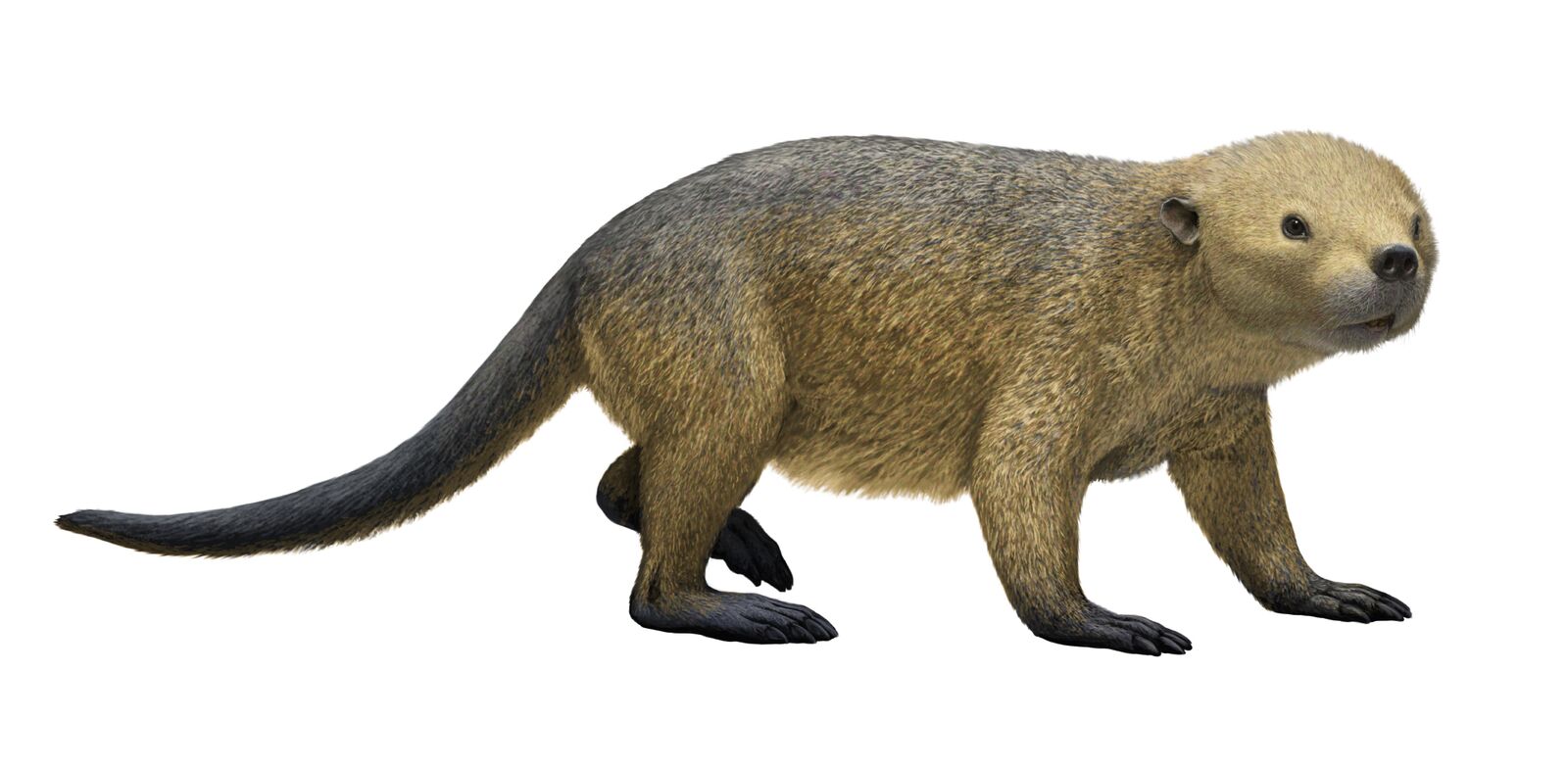

Over the next few years they found thousands of fossils and many plant and animal species new to science, from the raccoon-like Loxolophus to the beaver-like Taeniolabis to the wolf-sized Eoconodon, “which we lovingly call the wolf-pig,” Lyson says. Their team analyzed plants from the time period, too, including thousands of prehistoric pollen grains.

In fact, Miller and Lyson say they collaborated with more than a dozen other scientists and experts to analyze and document their findings.

And with all of this data, they started to piece together the story of what happened during the first million years on earth after the asteroid hit—a story told in their paper recently published in the journal Science.

"This moment in time is so critical because it is the moment from which everything that lives on earth today emerged." - Ian Miller

“This moment in time is so critical because it is the moment from which everything that lives on earth today emerged,” Miller says.

That’s a pretty big deal. So what did they find out? Miller and Lyson explain:

“So let's start in the Cretaceous,” Miller says.

“We're hit by an asteroid moving about 150,000 miles an hour. It slams into the Yucatan Peninsula and blows a hole in the ground about 120 miles across and 20 miles deep. It sends a shockwave and firestorm to Alaska in five minutes. And there’s tsunamis that make it to northern Texas and blocks of rock the size of cars make it to Haiti.”

We lose three quarters of all species on the planet -- animals and plants -- almost in the blink of an eye. And we lose all the dinosaurs. But, life bounces back.

“From this devastated landscape, the earth turns green again in a matter of years or decades,” Lyson says, describing a land exploding with ferns. “In the understory of this fern world, as we call it, we have really small things. The largest mammal that survived that mass extinction weighed about one pound, about a rat-sized animal.”

Forests of palm trees then start to flourish.

“And here we see mammals start to rebound in terms of diversity, in terms of their numbers, as well as their size,” Lyson continues.

Now trees in the walnut family start to crop up.

“Since the walnut family includes the pecans, we've named this the ‘pecan pie world,’” Miller says. “And we can see the mammals really taking over everything. It's their time.”

700,000 years after the asteroid struck earth, the world's oldest legume or bean pod appears. This was one of Miller and Lyson’s most prized discoveries at Corral Bluffs.

“So we've dubbed this the ‘protein bar moment,” Lyson says.

Because of these new protein-rich food sources, mammals, our early ancestors, are now growing a hundred times bigger than the rat-sized survivors of the mass extinction. Some now are as big as wolves. And we won’t see this kind of evolutionary size jump in mammals for another 30 million years.

What’s more, says Miller, they discovered these changes were tied to fluctuations in climate.

“We think the warm intervals are driving the migration of plants, maybe even the evolution of new types of plants,” he says.

And that, in turn, is what supported the growth and diversification of animal species.

“That's the story in a nutshell, so to speak,” Miller says.

"It's such a remarkable discovery that was right here in our backyard." - Tyler Lyson

Lyson adds, “It's such a remarkable discovery that was right here in our backyard.”

The Rocky Mountain West is actually one of the most fertile fossil regions in the country.

“It's from New Mexico to Utah to Montana and here in Colorado, that the Rockies come up and create this great environment to preserve fossils,” Miller says.

When mountains like the Rockies start to erode, sediment piles up in the basins below, in rivers and ponds, Miller explains, and these areas became the “tape recorder” for the period on earth between 70 and 40 million years ago.

And the findings here in Colorado Springs have contemporary relevance. They open a window into understanding what can happen to life after mass extinction. Miller points out we are in the middle of another mass extinction of species right now, albeit more slow-moving than an asteroid.

“We are the asteroid that's wiping out ecosystems and species today through a whole variety of processes,” Miller says.

"We are the asteroid that's wiping out ecosystems and species today through a whole variety of processes." - Ian Miller

He says their research shows how life has been resilient in the past and that it can come back after mass extinctions. But it comes back changed.

“So what you see outside today,” Miller says, “if that goes extinct, it's extinct forever.”

For now, he says, they’ll keep studying the fossils from Corral Bluffs to learn as much as they can about how today’s world came to be.

Miller and Lyson’s discoveries are showcased in a new PBS documentary called “The Rise of The Mammals” and in an exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science called “After the Asteroid: Earth’s Comeback Story.”

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUER in Salt Lake City, KUNR in Nevada, the O’Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, and KRCC and KUNC in Colorado.