Even before two Colorado universities had serious and public incidents of racism on campus within months of each other, the universities had long struggled to recruit and retain a diverse student body and staff while making the environment welcoming to all.

Annual diversity summits and seminars, where experts talk about gender and sexuality as well as race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, aren’t enough, students of color say.

At Colorado State University, freshmen attend a mandatory diversity seminar as part of orientation. Earlier this month, CU Boulder hosted its Diversity and Inclusion Summit with sessions on white supremacy on college campuses, DACA, racial representation and more.

But students of color at both schools say addressing such critical, personal and ever-present issues once a year is not enough. They want a more diverse student body, faculty and staff. And they want their administrators to be more proactive in how they approach diversity rather than only addressing racism when problems arise.

At the University of Colorado Boulder, some students say that while they may not have experienced overt racism, there’s still an overwhelming feeling that they don’t belong on campus and that they’re missing out on opportunities their white peers have access to.

“Even when there's not overt racism, there's this deep discomfort that people of color feel on campus just because we know that other people are uncomfortable around us,” said Lauren Jade Arnold, a graduate student at CU Boulder.

One of the more high-profile racist incidents on campus was in October, when a transient woman not associated with CU Boulder yelled racist remarks at students in the Engineering Center. It was captured on Snapchat. The woman was arrested days later but not without student protests and statements from university officials denouncing the racism. Days later, a car on the Hill was vandalized with a racial slur.

CU said it’s been working on the problem for decades.

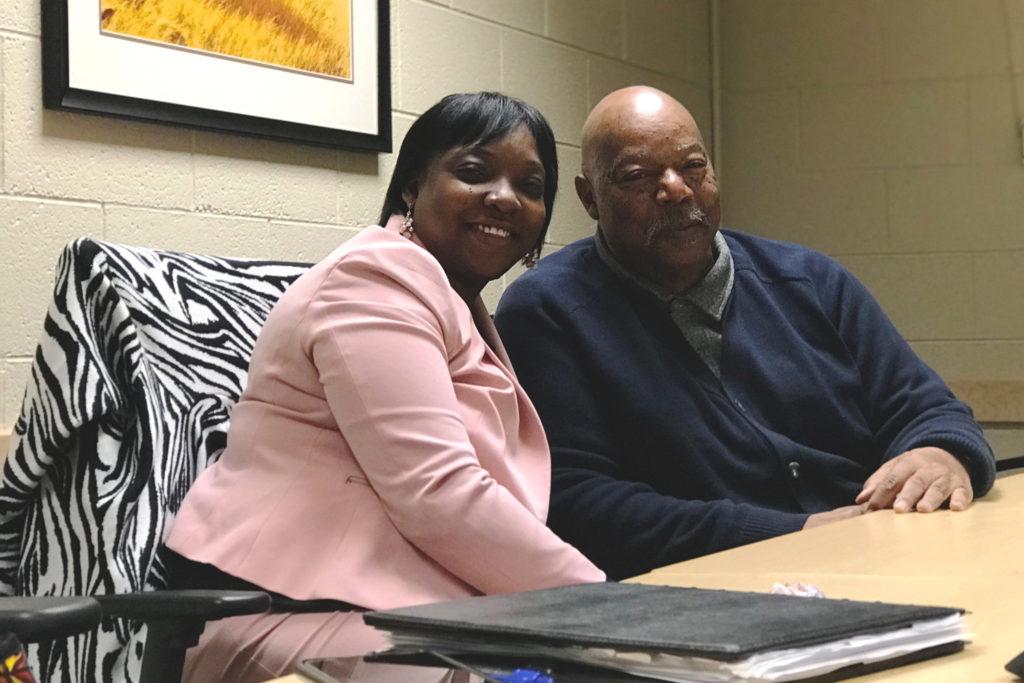

Alphonse Keasley is the Associate Vice Chancellor in the Office of Diversity, Equity and Community Engagement and he said he’s seen the campus evolve since the ‘60s, when he first came to the campus. Back then, students’ main focus was getting more students of color accepted into CU.

Fast forward to the ‘80s — more students of color started coming to the University, though Keasley said the data looks flat. It wasn’t until the ‘90s when CU Boulder began setting up academic programs for students from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds known as the CU LEAD Alliance.

In 1999 the university developed a diversity plan called “A Blueprint For Action,” which had three goals — to recruit, retain and graduate a diverse student population and to employ a more diverse staff, faculty and administration. That third goal — to build and maintain an inclusive campus environment — is where the school still largely faces challenges, Keasley said.

“Where we didn't see the great change was with regard to climate and I continue to underscore the reason that climate is so difficult is that when people don't know how to engage with difference… then it continues to be — to feel like it's a less than welcoming environment,” he said.

CU President Mark Kennedy and CU Boulder Chancellor Philip DiStefano both made statements condemning the most recent racist incident, saying there is still work to do to make the school more inclusive. They also talked with members of the Black Student Alliance and said they would meet the student group’s list of demands.

Critics say administrators aren’t being proactive enough.

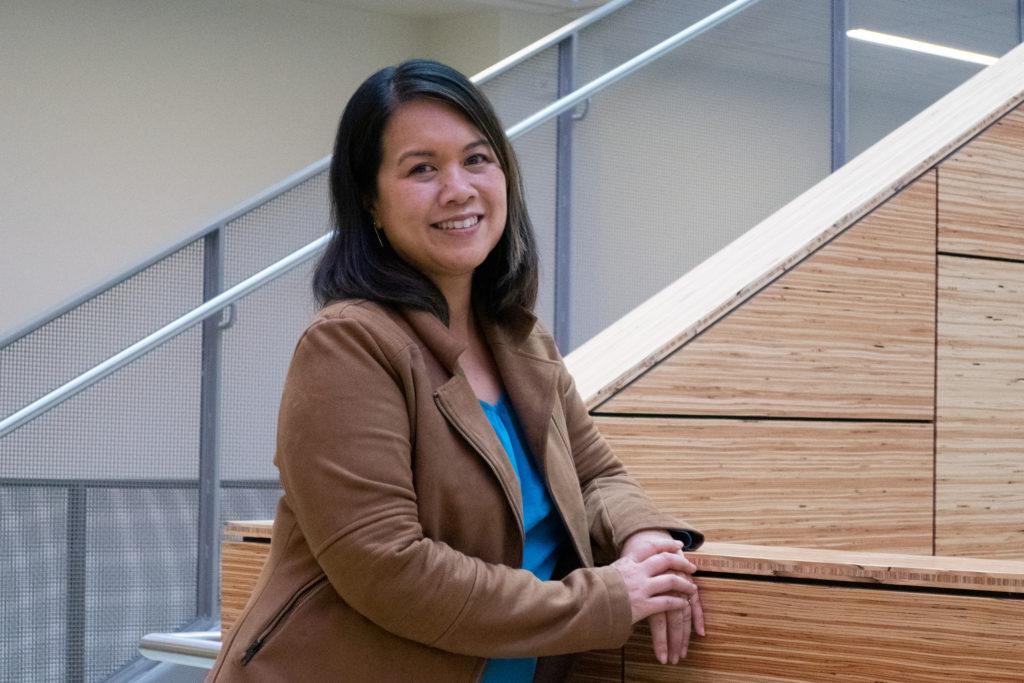

Angie Chuang, an associate professor in CU’s College of Media, Communication and Information said that’s part of the problem. Chuang teaches a course on how to discuss social identities like race, socioeconomic class, gender and sexuality within media.

“I think there's still a feeling that it's uncomfortable or that we only need to talk about it when something racist happens or when there's an incident,” she said. “It's not a constant conversation.”

Before teaching at CU, Chuang taught at American University in Washington, D.C., where she developed a diversity course that the administration required after several high-profile racist incidents at the school.

Chuang said although the course was a good exercise for students, she’s not sure if making diversity education mandatory is the best solution for overcoming racism on campuses. For one, not everybody in the class is ready for the class.

“Anytime you make it mandatory, there's immediately a pushback or resistance about, ‘Oh, this is just political correctness.’ Or we're just here to be touchy-feely and feel good about ourselves and check off a box,” she said. “Not everyone would be a productive contributor to a class if it didn't happen at a time that they were ready for it.”

At some colleges, some students may be meeting people of color for the first time ever, Chuang said.

In her class at CU Boulder, she had a first-year student who was from a rural town in Colorado, who was open to the material in class but would sometimes push back, arguing that putting people into categories or looking at race issues isn’t helping anything, but causing more divisiveness. Chuang said as the semester went on, the student admitted that the first time she ever met an openly gay person was at CU Boulder.

“And she acknowledged that the first time she interacted meaningfully with a black person was on the CU campus after she had left her town and graduated from high school,” Chuang said.

Blanche Hughes, vice president for Student Affairs at CSU, is leading the school’s new diversity initiative and said it’s true that some white students arrive with certain stereotypes. They likely have never been called out for inappropriate things they say or do, either.

But she said universities are a place that help them grow up.

“That's why you go to college, so that you can meet people that are different from you and that have different backgrounds and different perspectives,” she said. “We all come with different stories and to be able to appreciate and learn that. And in some cases, unlearn things that perhaps stereotypes or things that you've heard about a particular group or population because you haven’t been exposed to them.”

Hughes said it’s part of the university’s responsibility to teach students how to engage and have uncomfortable conversations. First-year students attend a half-day diversity seminar as part of their orientation.

Students of color do a lot of emotional labor and they’re tired of it.

Arnold, the CU grad student, has been on campus for five years. She said even if her white peers aren’t getting a comprehensive cultural experience prior to college, everybody needs to be held accountable for their actions regardless of their background and level of understanding.

“We can't be the expense for that,” she said. “We can't be like the scapegoats or the test rats for people who have never been exposed to diversity or taking the time to educate themselves about it.”

Arnold grew up in Aurora and said about 75 percent of her high school student body identified as people of color. She doesn’t want to speak for all students of color but said there are experiences she and her peers of color all have in common.

“It just feels like no one really understands you or knows how to talk to you if they're not also a student of color,” she said. “And other times when it's not just a lack of understanding, there's a more hateful racism where people just don't want to hear anything that you have to say or they shut you down in classes or they make it clear that they think that you're lesser.”

Arnold said on the first day of one class, her teacher had students play “diversity bingo,” where one bingo spot asked students to find somebody with a different cultural background from themselves.

“It just became this really gross game of people coming up to the only minorities in class and then people like judging people based on how they look to see about their other identities,” she said. She didn’t tell her teacher how inappropriate the game was because, she said, she didn’t feel like it was her responsibility to educate her teacher. Her other concern: How might that conversation impact her grade?

If she’d reported it, it would have been among hundreds of complaints against CU students, employees and affiliates in a year’s time.

CU encourages students to report bias-motivated incidents to police, the Office of Institutional Equity and Compliance, the Office of Victims Assistance or the Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution. The victim can decide whether or not they want to remain anonymous. Sometimes these incidents can go through a conflict resolution process or a police report can be filed. Other times the victim can be turned to confidential counseling.

From July 2018 to June 2019, CU Boulder’s Office of Institutional Equity and Compliance received 117 complaints against students and 347 complaints against employees and affiliates under the school’s discrimination and harassment policy. The most commonly reported cases for both students and employees were related to race.

In a 2018 report, CU said the office received more than 1,300 complaints during the year, triple the number received in the past three years. CU said the high number of complaints indicated people are trusting the school more to resolve concerns.

A spokesman for CSU said its community members are also encouraged to report incidents of bias but because the system to report is newer, the school does not have a specific or accurate account of reported incidents yet.

In September, four white students at CSU posted a photo of themselves wearing blackface on social media. The photo made a reference to the movie “Black Panther.” One student involved told the school’s student-run broadcast station that she had no idea about how the photo could have been perceived and said she researched the history of blackface following the incident.

The school said it wouldn't punish those students because their actions were protected by the First Amendment, and that students, faculty and staff could generally post anything they want online. CSU students were outraged and hundred students protested during the fall address and chalked a plaza on campus. A few weeks later, CSU President Joyce McConnell announced a new plan called the Race Bias and Equity Initiative. The school put out a call for proposals from students and staff on how to combat racism.

There may not be a one-size-fits-all fix for universities. Regardless, the real work has to happen outside of class

“When you come to the university and you've grown up in a homogenous or the same group of people, the university may be the first time that you come in contact with difference,” Keasley, the CU Boulder administrator, said.

He said in a metropolitan and urban environment — like Metropolitan State University or CU Denver — there are different groups of people coming together, who have already “worked through their nastiness.”

Sixty-eight percent of students at CU are white, according to the university’s 2018-2019 Diversity Report. Students of color make up 27 percent of that total, not including international students. At CSU, students of color accounted for 22 percent of students in 2018. Many of the students at CU Boulder and CSU come from Colorado, California, Illinois, Texas, New Jersey and Washington.

At the University of Colorado Denver, though, nearly half the student body is made up of students of color, according to the 2018-2019 Diversity Report.

Sophomore Daniel Casillas is studying biology there and is part of the student government. He said being at the school has been eye-opening because he’s meeting people from a wide range of backgrounds and with different perspectives, which has encouraged him to get involved.

“I think on paper, CU Denver is diverse and in person, CU Denver is diverse,” he said. “Looking at the collective group, there's not only one specific race or one specific gender or one specific sexuality, it's a collective mix of people.”

Chuang, the CU teacher, is still on the fence about what the right solution is. And measuring whether or not one thing is more successful than the other is complicated.

“Do you measure it because there are fewer racist incidents?” she said, adding that the real work happens when students build relationships outside of class.

“That the students who walk out of class and have a conversation in the dining hall, or after class or working on a group project might be more likely to talk about a racial issue. And not even in the context of racism, but just to bring up race, or to talk about a movie they watched or a song they heard in the context of how race might inform that," she said. "And I think just starting those conversations and building those more organic relationships is where we're going to make progress on this issue.”