On Nov. 9, 1989, after nearly three decades of dividing the East section of the city from the West, the Berlin Wall fell. During the height of the Cold War, unauthorized crossings could result in death, and according to recent counts, at least 140 people died at the wall.

When it came down, thousands stormed the wall. Some even took hand tools to chisel off chunks. It signified the end of what most considered to be an oppressive communist regime, and would soon pave the way for German reunification.

Colorado artist Mary Mackey was in London that day. Riveted by what was happening, and knowing she soon had to return to Denver, she thought, “I've got to get to Berlin to see the wall before it comes down.”

After she arrived in Berlin, she read in an art magazine about artists being recruited to paint murals on the east side of the wall.

Artist David Monty, from West Berlin, and Heike Stephan, an East German artist, had gotten permission from border officials to turn a nearly mile-long stretch of the wall on Mühlenstrasse into an open-air art gallery. It would become known as the East Side Gallery.

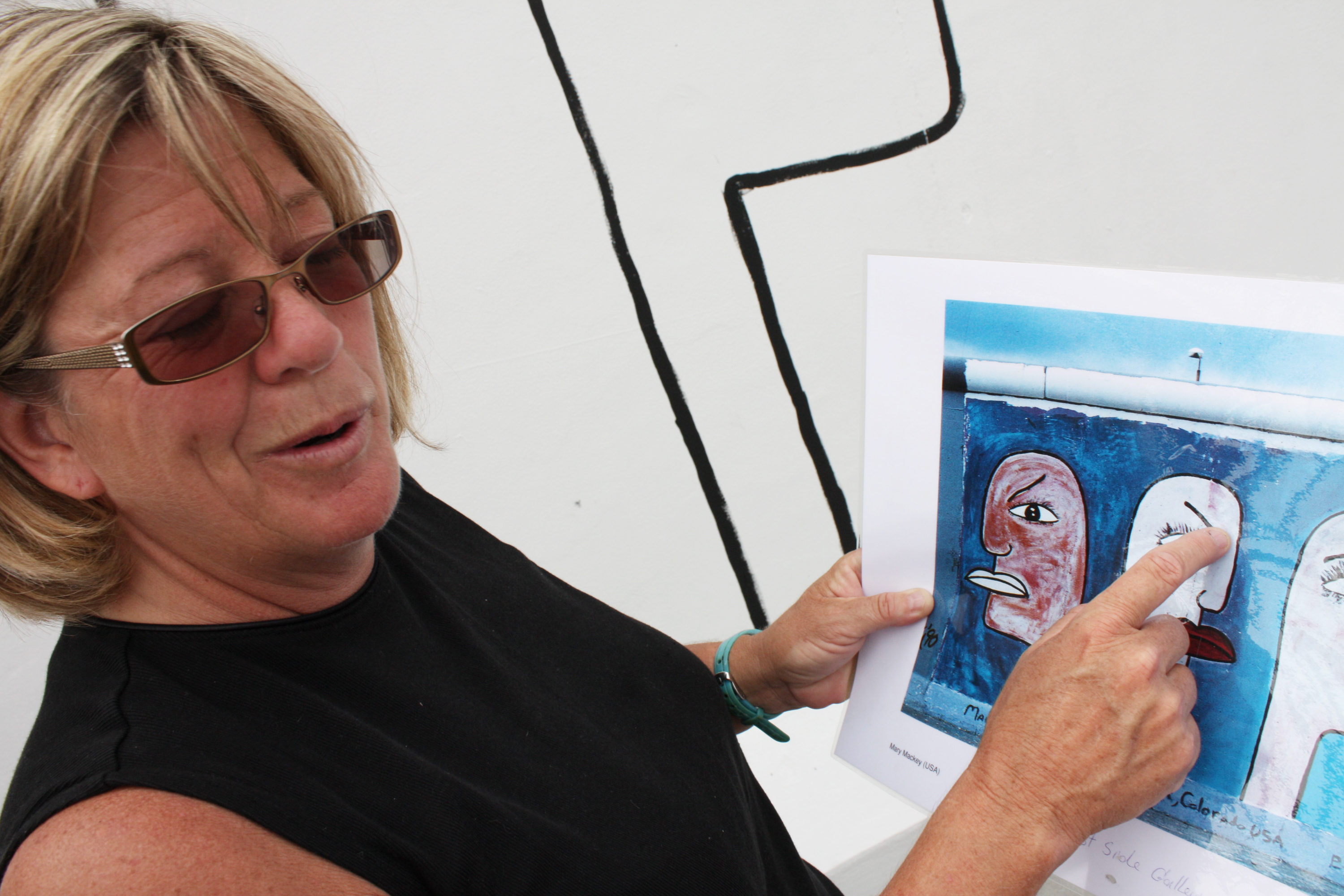

“It was the first time anybody got to paint on the east side of the Berlin Wall,” Mackey said, pointing out how the west side of the wall had been adorned with graffiti and street art for decades. “So that was really special.”

Mackey was a photographer, she wasn’t much of a painter back then. But she had a sense it would be extraordinary, so she asked if she could participate.

“It was kind of the first time I was in the right place at the right time and you have to put yourself out there to make things happen,” Mackey said. “And I really did put myself out there to make it happen. None of us knew how long the wall was gonna stay up. We didn't know what was going to happen to it.”

In August 1990, Mackey painted her mural in two vignettes. In the first, two faces in profile look away from each other with a frown. In the second, those same faces gaze toward each other with a smile. She titled the work “Tolerance.”

“I was over there for about six months before I ended up painting the piece, and I recognized that, between East and West Berlin, there was a lot of misunderstanding of people,” Mackey said.

Years of separation kept Berliners in different clothes, different cars and very different economic and political systems. Mackey wanted to create “acceptance of each other” in her art.

It took about nine months — and 118 artists from 20 countries — to complete the gallery. Painting started in January 1990, “when it was really cold and we only had a few artists,” said Christine MacLean, an assistant David Monty took on after she answered a newspaper ad for an “English-speaking assistant to help with an art project on the Wall.”

There wasn’t a formal selection process because “it was the emotions and feelings that were important,” she said. Any artist’s submission was accepted so long as the message they sent wasn’t about hate because, as it soon became clear, this was to be a “living monument to joy.”

“How many monuments to joy are there in the world and is it not more ethical to spread joy than terror and horror,” MacLean asked. “And that was just the sheer emotion [when the wall fell] the joy that was there... that the wall’s opened... and we can travel and we're free.”

Of the wall muralists, Scottish artist Margaret Hunter, had experienced life in Berlin with the wall. For her, painting on this physical representation of oppression was a simultaneously poignant and joyous moment.

“This is the wall, what I saw on television when I was 16, looking at people coming under tunnels and being shot,” she said.

She called it an “amazing time” to be painting alongside all of those Berlin Wall artists.

“We didn't have enough ladders, the paint wasn’t that brilliant and we could hardly understand each other,” Hunter said. “But we chatted and talked, and the atmosphere was euphoric.”

The East Side Gallery became a heritage-protected landmark in 1991. Despite early preservation efforts, it didn’t hold up well against erosion and graffiti. A large restoration project led by painter Kani Alavi launched in 2009. It was not, however, without controversy.

The wall was repaired and the initiative invited the artists back to Berlin to recreate their original murals in time for the 20th anniversary of the wall’s fall. Some artists felt things had changed since 1990 and, if they were to paint again, they might paint something different. They alleged they were told if they refused to reproduce their works, then someone else would. There were also disputes over compensation. A number of artists sued.

Mary Mackey did repaint her mural. She wanted it to live on and she hadn’t been back to Berlin in nearly two decades.

“I stayed for an entire month. I had a blast.”

She said in a Colorado Public Television documentary she wasn’t “sure how close I was going to get [the original piece].” She had doubts she could pour the same feeling into it, but in the end, she was “actually pretty pleased with it.”

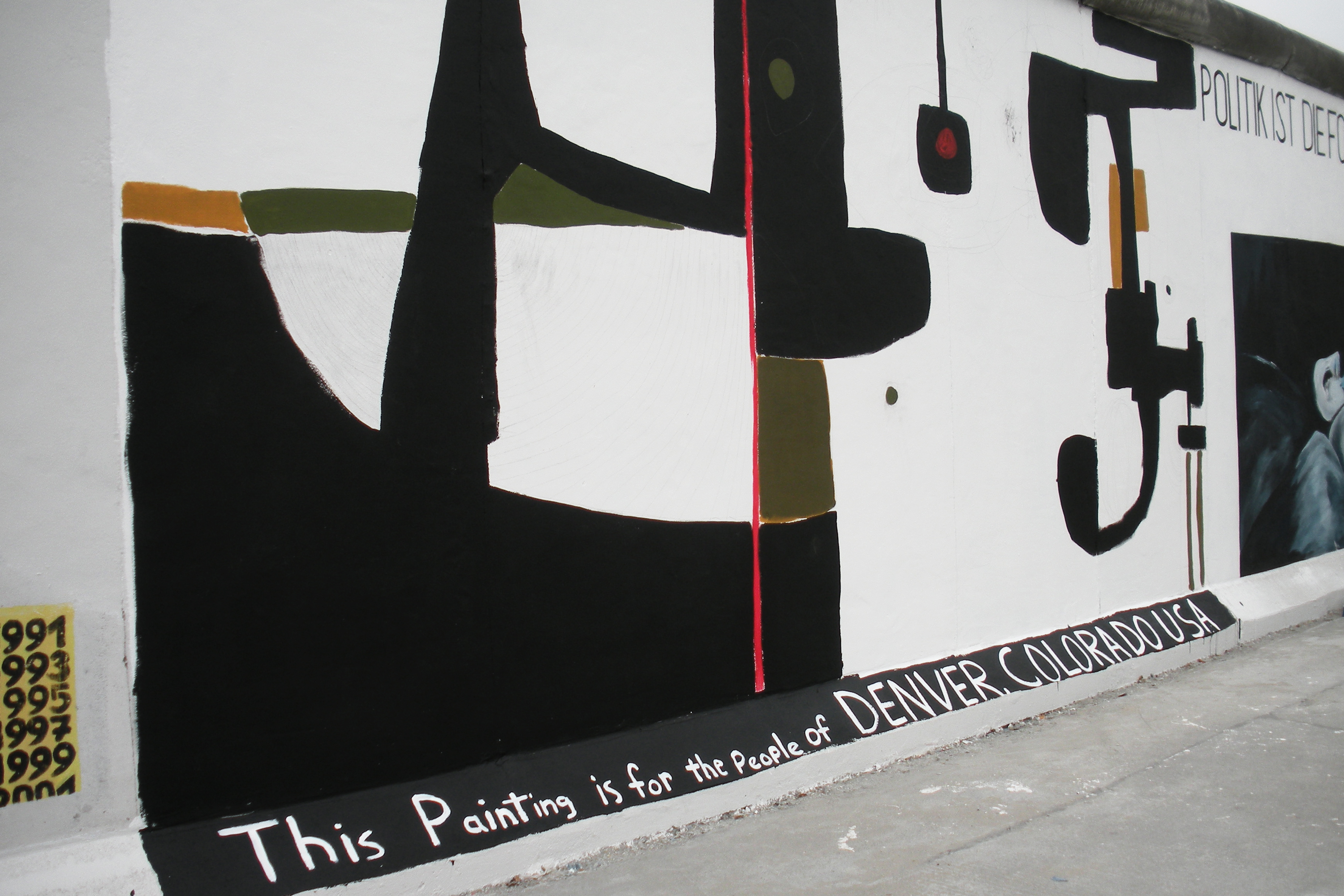

Though, before she started on “Tolerance,” she decided to paint an abstract work on the wall.

“It was kind of a bit in retaliation of what was happening back here in Denver; that I was not invited to a show that had abstract artists and I had been an abstract artist for a long time,” she said. “I painted this abstract piece... and I wrote at the bottom of it, ‘This is for the people of Denver, Colorado.’”

She kept it up for four days and photographed it before she put her original artwork back up.

More than four million people have already visited the East Side Gallery in 2019, according to the Berlin Wall Foundation, which took over management of the gallery about a year ago.

Julia Reuschenbach, who heads the East Side Gallery division for the foundation, said it’s important to preserve the original artwork, despite some artists expressing that the work should change to reflect current affairs.

“I think many people especially come here to see the special art and to see how the artists were feeling in this moment in 1990,” Reuschenbach said.

Some of the foundation’s hopes for the East Side Gallery include adding museum-like plaques to each piece and to have more educational programming.

The foundation also promised to stop another threat to the gallery: commercial development.

Pieces of the gallery have even been removed and relocated as Berlin boomed. Many artists have argued that high-rises overshadow the gallery and take away from the authenticity of the area.

Colorado billionaire Phil Anschutz has been an investor in this part of Berlin since about 2004 and owns property along the gallery, including the Mercedes-Benz Arena, the Mercedes Platz Entertainment District and a parking structure.

More than a decade ago, a portion of the wall was opened up across the street from where the arena and entertainment complex now stand. Moritz Hillebrand, vice president of communications with AEG in Germany, said the gap was necessary to give the public secure access to a park along the Spree River.

“If you have a park that is located between water and a wall, at the moment it gets dark, it becomes a space of fear,” Hillebrand said.

Now there are regulations in place to prevent any more of the gallery from being displaced, and the Berlin Wall Foundation has taken over ownership of the green spaces, said Julia Reuschenbach.

Uwe Frommhold, vice president and COO of AEG in Germany said they’re committed to preserving the gallery and are talking to the foundation about contributing money toward that. There’s no formalized agreement yet, but they hope to finalize it soon.

“The East Side Gallery is a monument for Berlin and it has to be preserved,” Frommhold said. “This is what we can do to ensure making it part of the new Berlin as well.”

For a long time, Mary Mackey felt embarrassed by her East Side Gallery painting. She said the artwork looked “childlike.” But over the years, she’s heard from many who’ve told her how much they like her work.

“One of the things that they liked about it is that you're driving down this big road pretty fast, but you can look over at [the mural] and know what it means,” she said.

And that’s helped her reflect on her involvement more broadly, how she got to help capture the feelings and emotions of that moment in November of 1989.

“It was really important for me to be involved with it,” she said.