At George Washington High School in Denver, in the dance room, a couple of dozen students sit in chairs in a half-circle, silent, feet on the floor, eyes closed. Instructor Beverly Jacobson speaks softly.

"I'm going to ring the tone, and just follow the tone back and open your eyes when you can't hear it anymore.”

She taps a metal chime. Diiiiiiiiiiiiiing.

It’s Mindful Monday, a new part of the students’ physical education class where Jacobson uses the Inner Strength Teen Program to teach students to meditate.

Research shows teens today deal with high levels of stress, anxiety and depression. Studies of adults have shown mindfulness helps ease those conditions. And an emerging body of research shows it may help boost resilience in adolescents via better “cognitive performance and emotional regulation.”

In response to the CPR News series Teens Under Stress, which explores the pressures teens today face, teens, parents and educators suggested we look into efforts at schools to bring calm to students’ lives. Jacobson wrote in and suggested her classroom.

She writes on a whiteboard and talks about how culture has changed to make life more complicated and filled with choices.

“Today we're going to talk about specifically what's most stressful for all of you,” she tells the students.

For the next activity, the instructors ask the teens to scooch together as a group in the middle of the room “cause we're going to vote by going to one side or the other depending on your preferences or how you feel,” Jacobson said. “Okay?”

Programs like this are popping up around Colorado, and the U.S., to help teens build healthy habits and relationships through mindfulness. One main idea is encouraging students to do some self-reflection. The first question this morning: are you shy or outgoing?

“Extrovert over here. Introvert over here,” Jacobson said as the diverse mix of students vote with their feet on more questions about their everyday lives.

“Early riser!” she said motioning to her right. “Night owl!” she said waving students to the left. These are high schoolers, so there’s just one lonely early riser.

Then they repeat, with Jacobson asking a series of questions. “Have a smartphone, don’t have a smartphone? ... Social media love it, hate it? … Do you feel physically safe at school, most days, over here.”

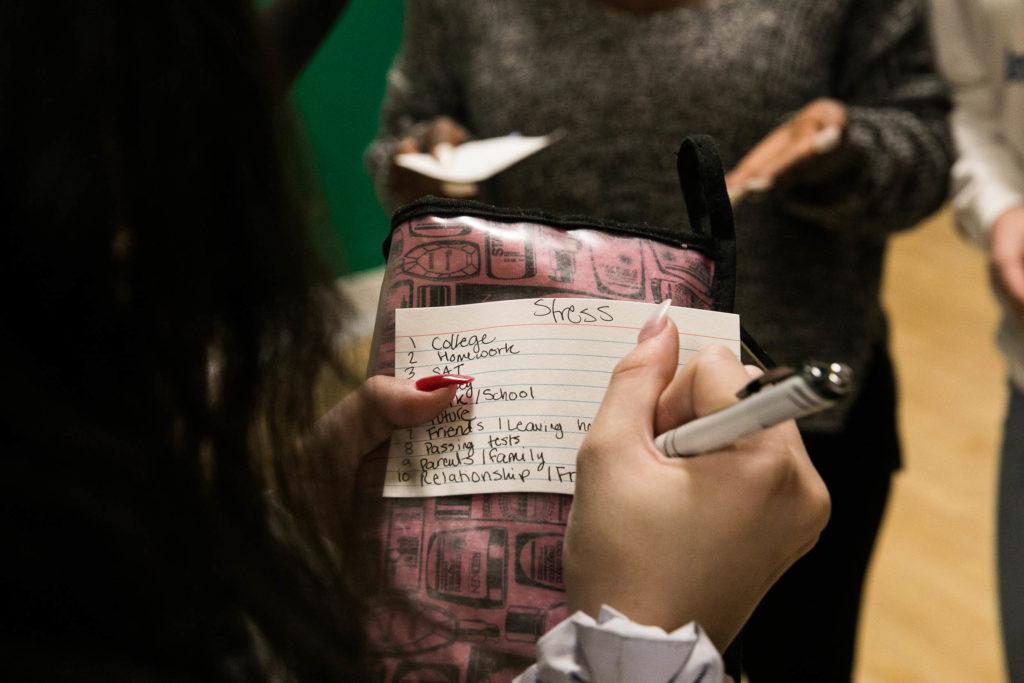

Many students signal they feel safe most of the time but not all the time. Next Jacobson, asks the teens to break into small groups to talk about what adds to their anxiety.

The students take turns answering.

“Work. School. Future, that’s stressful. Friends and relationships, that’s stressful.”

When asked what makes them happy, music is high on the list.

“I put my friends, love my friends. They're great,” said one girl.

The Inner Strength program Jacobson teaches was first developed in Philadelphia. Its mission is to give youth, from primarily as-risk communities, tools to “self reflect, develop interpersonal skills, and gain perspective on how our culture and physiology affect us.” The program teaches evidence-based tools to promote “ease and self-reflection,” brain science and the “art of the relationship,” which involves learning compassion for yourself and others.

A multi-year study of the Inner Strength program by Syracuse University found measurable quantifiable improvements for students in several key metrics: self-regulation, self-compassion and perceived stress.

If you need help, dial 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also reach the Colorado Crisis Services hotline at 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat.

One key activity is for students to keep a journal. The group also focuses on small group discussions, walking meditation (literally using the natural movement of walking to cultivate mindfulness), and eating mindfully, which entails students slowing down and paying attention to all of their senses while eating chocolate and other small items.

The students in the George Washington High course say this instruction has made a big impact on their mental health. A senior named Queensther says since taking this class she’s a lot better at dealing with life’s ups and downs.

“I get very tensed up, stressed, overwhelmed. So, it helped with my anger. It helps with so much I was going through, I easily calm myself now. I meditate a lot now,” she said.

Emmy, a freshman, said thanks to the class, she now meditates outside of school five minutes a day.

“I have a really bad habit when I get mad or like anger issues, I try to block people out and I blackout on everything. So, I think this class just helps you understand other people's feelings or your own feelings,” Emmy said.

Teaching teens about the adolescent brain is a key part of this curriculum. Fifteen-year-old Anisa plays basketball and says what she’s learned is making a difference on and off the court.

“I really utilize this class when it comes to breathing techniques. Those really help a lot,” she said. “I get a lot of information about how really the brain works and how my brain works and how to operate around other people and certain situations which I really love.”

But in most schools, there is not a lot of discussions, let alone instruction, about meditation, breathing techniques and the teen brain. Jacobson, a mother of two teens, is a longtime meditator herself. She says there are some hurdles to finding a place for mindfulness in a busy school day.

“The academic content, college prep, there's never enough time for students to get all of that stuff done. There's never enough money,” she said.

But Jacobson said investing in “coping skills and just life skills for kids helps them to do all that other stuff.”

George Washington High physical education teacher Narissa Stahl applied for a modest school grant to pay for this course and said it’s worth it.

“I absolutely think this is the missing piece to the puzzle in education," Stahl said.

These days schools can be pressure cookers, with high levels of academic stress, stress to excel in sports or other extracurricular activities. That’s not to mention students managing social and home lives, and, for some, jobs.

As CPR News has reported, teens cited academic stress as the number one stressor in their lives in one recent national survey. More than 4 in 5 said school was a “somewhat or significant source of stress” in a 2014 American Psychological Association survey. Nearly 30 percent reported “extreme stress” during the school year.

In dozens of interviews with teens, academic stress was also cited as a top reason for anxiety and depression. A focus on college is a big part of an increasingly demanding situation for some teens.

Stahl said before the course started some students sought counseling, but now they have strategies to help them cope. After the fourth week of meditation instruction, she polled the students. They told her the program was helping them do things like focus and get calm before taking a test, take a break when they need to de-stress and let go of unhelpful thoughts.

Stahl said students need to have some time just to focus on their inner selves. She notes they don’t have their phones out in class.

“I think that it's a way for them to take a break from technology. They never want to admit they need that break, but they truly do,” Stahl said. “They crave quietness.”

Makailah, a senior, agrees.

“This class eases the pain. It eases the stress. You just sit down and you get time to think.”

As the period ends, students return to their seats, Jacobson is back at the front of the room.

“Take a good deep breath in, feel your weight sink into the chair on the out breath…”

And after the final ring of the chime…

“Follow the sound of the tone.”

Diiiiiiiiiiiiiiiing.

...it’s back to their day.

We want to know more, and we hope you do, too.

CPR News will spend the next few months investigating the factors that have created the ultimate pressure cooker for some teens. We’ll go into their world through audio diaries, interviews, reflection and analysis. Most importantly, we’ll examine what teens, families and schools can do to let some of the pressure loose.

_

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story misspelled the name of a student. It is Queensther, not Queenster.