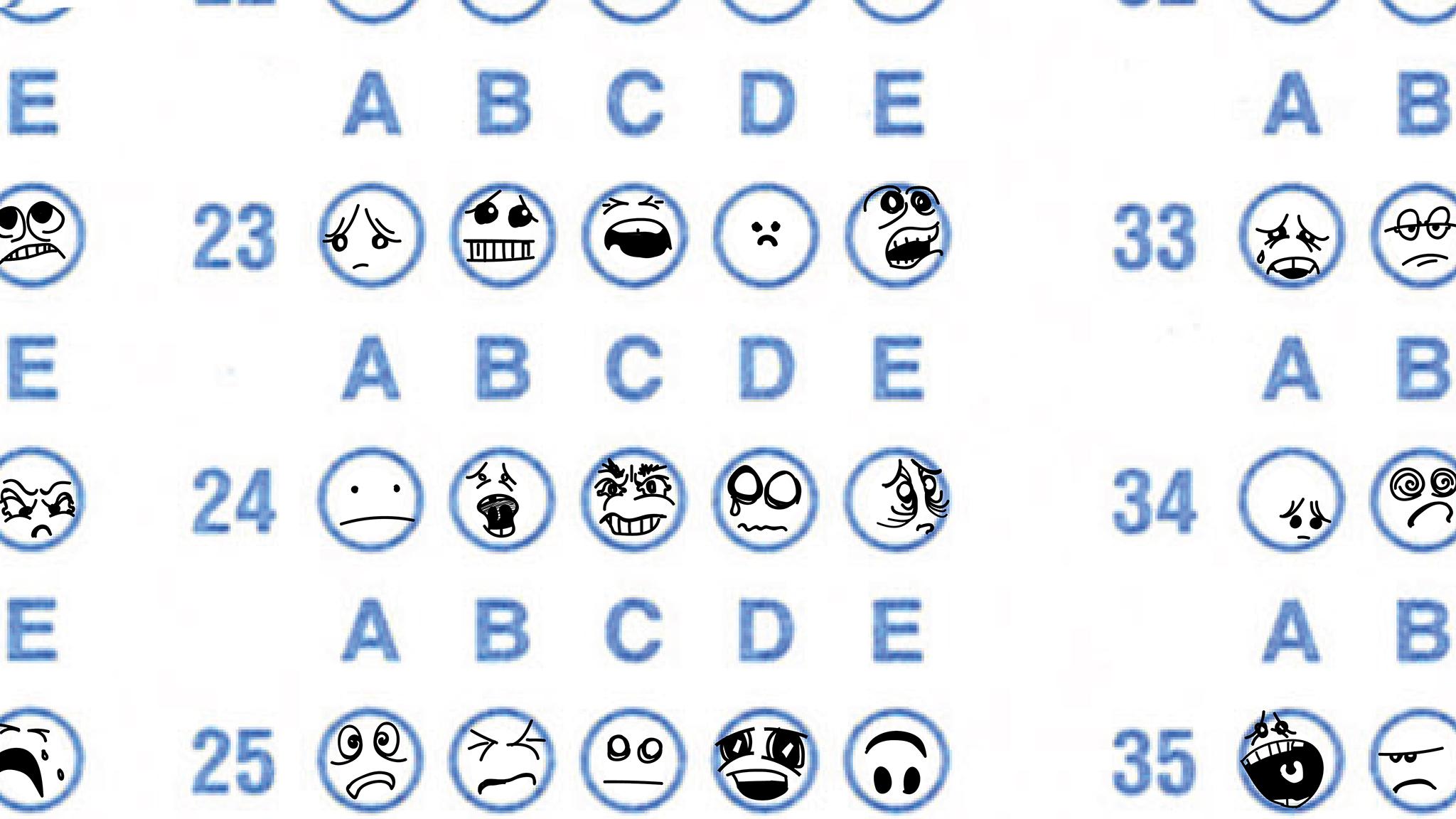

Earlier this fall, a group of Denver-area teenagers gathered for and led an intergenerational discussion of empathy, diversity, equity and inclusion. Afterward, that group of teens — all interns at the arts and youth development nonprofit PlatteForum — sat down with Denverite and Colorado Public Radio to talk about the things that stress them out most. Academic pressure stood out as an area with a variety of sore spots. The biggest pain point, though, seemed to be testing.

“Why do those tests have to define who we are and how smart we are?” Mixi, 16, asked. “Like, that's dumb.”

Students today face mounting pressure not just to get into college, but to figure out how to pay for an increasingly unaffordable education by working or by setting themselves so far apart from their peers that they’re awarded scholarships. It’s not just about grades. It’s about how many extracurriculars you can stack up and excel at. And in the age of total social media saturation, they face all of this while they’re in constant, public competition with their classmates.

They’re frustrated and, as we well know, highly stressed out. It’s difficult to measure, but it’s not difficult to see.

This is what the teenagers tell us.

“Our brains aren't developed are we're dealing with school, we're dealing with home. Some of us even have jobs that we have to go to every day,” Mixi said. “It's not like being a teenager is easy.”

Zaida, 17, chimed in: “Being a 2019 teenager is not easy.”

We hear this sentiment all the time and it's proved difficult to back up with anything more than anecdotal evidence. It’s not just about the moment, the pressure and the implications of each individual test. They might not have read the studies (though maybe they have) but they’re aware of what they say. Studies have again and again shown that standardized testing doesn’t translate to better cognition and hasn’t been found to have a causal effect on success later in life. Students know this and they know that on a local level, the tests can be more about their schools than they are about them.

The other thing they say, regardless of who they are or where they come from, is that the system is inequitable.

“Think about it: Like, SATs, you can pay for extra training on that. Not everybody can afford that. So most likely the people who are successful in that are gonna be white. Probably they have more money and they can afford to take those extra like courses to help do good on the SAT,” Zaida said. “And that leaves people who learn differently, who can't afford that, kind of left in the dust. And unless something about that changes, it's always going to be like that.”

Destany, who is 17 and identifies as Latina, said there are different standards for black and brown students like herself. They have to work harder to achieve the same level of success as their white peers, who often have more money, resources and support.

According to the National Center for Children in Poverty, 61 percent of black children and 58 percent of Hispanic children live in low-income families. And we know from many studies that students from wealthier families perform better on standardized tests and, as a recent CNBC story put it, “enjoy significant advantages throughout the college application process.”

In addition to a schedule packed with extracurriculars, Destany said, she works three jobs. She doesn’t think her test scores are strong enough to compete with some of her peers, so she works to prove her worth in other ways that might help her get into her dream college.

“I'm going to have to have five extracurriculars and like three scholarships and like four letters of recommendation for me to get into this school that has like a 60 percent acceptance rate,” she said.

Inequity has always been a problem, of course, but add onto it a heightened societal awareness of the problem combined with a lack of solutions and you’ve got a new level of frustration.

Technology is amplifying even the smaller stress factors, like homework.

As 17-year-old Machaela pointed out, widespread access to computers and the internet has blurred the lines between school life and home life.

“There's like a whole added stress of online homework because they can assign and have papers due online and not even within a school day,” she said. “It'll be [assigned] Friday and your paper's due on Saturday at 11:59 p.m. So it's like, OK, before this we would have been able to turn this paper in on Monday, but now they can totally change the due dates and stuff like that into like how it would not usually be without online resources.”

And the one thing almost every teen we talked to said is that through all this work, all this pressure, all this testing and box-checking, they don’t feel prepared for the real world.

If you need help, dial 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also reach the Colorado Crisis Services hotline at 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat.

This is what the stats tell us.

It’s difficult to track an increase in academic stress. It’s impossible to measure exactly the ways schools, parents and peers create anxiety in teenagers and, of course, it’s impossible to quantify feelings.

But one way we can measure it is by looking at the increase in standardized testing and the observations of counselors, doctors and parents.

In the 2015 book “Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation,” author Vicki Ables calls today’s students “the most tested generation in history.”

It started, she wrote, back in 2001, when today’s 18-year-olds were born. That’s when the George W. Bush administration enacted No Child Left Behind, signing into law nationwide math and reading tests each year in grades 3 to 8 and once in high school.

And as testing increases, so does student stress.

Psychologists and pediatricians have watched it ramp up since 2009, when President Barack Obama’s administration introduced nationwide Common Core Standards. That same year, the Council for Great City Schools conducted a survey of 66 urban school districts in the U.S., including Denver’s, and found that a typical student takes 112 mandated standardized tests from pre-K to graduation. That’s an average of eight standardized tests a year, though students are faced with the most tests in eighth and tenth grade.

Across Colorado, high school students spend a little more than 8 hours taking tests. A spokesperson for the Department of Education said the breakdown is 2 hours, 35 minutes for 9th and 10th graders for the PSAT and 5 hours and 45 minutes for 11th graders for the SAT and the CMAS science test. The biggest testing years in Colorado are in 6th through 8th grades, when students take between 8 hours and 45 minutes and 12 hours and 45 minutes of tests each year.

In a 2014 story by Rhema Thompson for Florida public radio station WJCT, a pediatrician reports witnessing an “incredible” increase in anxiety over five years. She also said there’s an uptick during big testing months. From February to April, she said, she sees a new patient each day complaining of stomach aches and panic attacks brought on by test anxiety.

It may be just one story, but Thompson reports that it’s not isolated:

[University of Hartford Psychology professor Natasha] Segool has been studying the links between anxiety in children and high stakes testing for the past six years. A 2009 study she conducted of third-, fourth- and fifth-graders in Michigan found that students reported being significantly more anxious when taking statewide assessments compared to other classroom tests.

About 11 percent of the children surveyed reported severe psychological and physiological symptoms tied to the assessments.

“In the scheme of things, that suggests that 89 percent of students may have a heightened reaction in the testing situation but they’re not experiencing clinically elevated levels of anxiety,” she said. “Is that a problem? I think that’s a really good question that we need to look at.”

Ten years since Segool’s study and five years since Thompson’s story, parents and teachers aren’t feeling like that really good question has been answered.

Looking into the effects of standardized testing for a 2016 project at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Christina Simpson found that polls showed that “49 percent of responding parents were concerned that students are experiencing too much standardized testing” and that 67 percent of public school parents surveyed “felt that too much emphasis is placed on standardized testing in the public schools in their communities.”

A 2019 poll by the educator organization Phi Delta Kappa International — more commonly known as PDK International — found that 29 percent of responding parents and 50 percent of responding teachers see pressure on their kids to do well on tests.

And all this testing doesn’t seem to be helping students. As the New York Times recently reported, the latest results of an international exam show no improvement from American teens in reading and math since 2000 — two years before No Child Left Behind. Meanwhile, the achievement gap between low and high performing students has been growing.

In a report for Education Week published earlier this month, Dan Goldhaber & Umut Özek wrote, “There is a vast research literature linking test scores and later life outcomes, such as educational attainment, health, and earnings. These observed correlations, however, do not necessarily reflect causal effects of schools or teachers on later life outcomes.”

That’s because there are so many other factors involved. For one thing, students who work hard at taking tests might just simply be harder workers in adult life. For another thing, test scores could be representative of inequities outside the classroom rather than a student’s intelligence. A teen who does poorly on tests might not have a supportive family or might be working after school and unable to study.

And all of that applies outside of testing. It applies to getting good grades and building a resume packed with a well-rounded selection of extracurriculars. It applies to the ability to get good sleep and eat healthy meals. It applies to just about every factor and metric of success.

So what are we doing about it?

Teachers and counselors know there’s a problem — maybe as deeply as teens do. They live the problem every day and though they hold more power than their students, it hasn’t been enough to bring about change.

“Testing has not been good for a lot of our students,” said Kathryn Brown, a counselor at Colorado’s Finest High School of Choice. “[They think,] ‘If I don't get at least a 1200 on my SATS, then I have failed completely and I'm a miserable failure at life.’

“Teachers are not feeling like they have a say in any of it, which is creating burnout, which is creating mental health issues for teachers, which then makes them less effective in the classroom. That teachers are feeling overwhelmed and not respected and not valued as professionals, which trickles down to students.”

That brings us to the top — the district officials and other school leaders.

Much is being done to address the symptoms. The Colorado Department of Education, for example, offers a wealth of health and wellness resources including fact sheets, grants, health and wellness staff, youth mental health first aid training and several state-wide mental health-related programs.

At George Washington High School in Denver, for example, students are practicing meditation and mindfulness in school. (Watch the Teens Under Stress series for more on school-based solutions.) .

Individual districts, of course, have similar resources. But mental health will never not be an issue — which is to say that these sorts of things would exist no matter what kind of academic stress students feel.

So what’s being done to get at the root of the problem?

Denver Public Schools Superintendent Susana Cordova and Jefferson County Public Schools Superintendent Jason Glass both told CPR News there’s been a movement to shift the way kids are tested and the way they’re taught in ways that better prepare them for the real world and account for individuality.

Glass, who’s been working in education for about 20 years and is in his seventh year in Jeffco, said the education system is at a “transition moment.” After decades of focus on memorization of facts, school systems are beginning to focus more on problem-solving, creativity, communication, critical thinking and “adapting to different situations and circumstances.” Part of that is because the actual skill of memorization has lost value in a world where facts are at our fingertips. The other part is an acknowledgment that memorized facts don’t prepare students to be on their own in the world.

“We've been working to try and mitigate [pressure] by changing what learning is like in our schools,” Glass said. “And by that I mean I'm trying to change the experiences that students have so that they more closely reflect real-life work and authentic work and things that are interesting and meaningful to students and fewer things that are purely just busy work that only has currency or meaning within schools. So one of the ways that we're getting at this problem is through trying to make schoolwork more engaging and meaningful to students so that it has more relevance and creates greater engagement.”

Glass points to Pomona High School in Arvada as an example. Instead of just memorizing facts about the Civil War, students also participate in a mock Antebellum Congress where they try to negotiate a solution to avoid the war. That means they need to effectively communicate, create novel solutions, and adapt to changing conditions, he said.

Glass and Cordova, who has 30 years in education, both said that testing has some value — and a healthy amount of pressure is good preparation for adult life. The trick, Cordova said, is balancing the need to measure learning with the need to give kids an education that isn’t focused on their performance.

At DPS, they try to strike that balance with flexibility in test participation.

“I'm a big proponent of site-based flexibility. Each school has the opportunity to determine which assessments from the district that they'll participate in,” Cordova said. “We do offer common interims, but it's a site-based choice to participate or not. And I think that's in part a way to say, ‘How do we have school teams be invested in the assessments that they're administering and use that data for the purposes of making changes and shifts in instruction.”

The district also successfully lobbied for shorter state assessments and pushed for a move away from the old CMAS assessments and toward college readiness exams like the SAT and PSAT.

If testing is going to stick around — and both superintendents said it will — it needs to look different. The problem, Glass said, is that there hasn’t been enough discussion about the limitations of testing.

“They're working alone and they're working under time pressures. Do you have an experience that's like that in life or in work?” he said. “It's an alien, sort of artificially contrived environment that we are testing students in that doesn't really measure how successful they will be as adults, especially when we factor in how closely correlated the results are on standardized tests are with student background, demographic factors.”

“Any system that's purely based on test scores is going to exacerbate inequities,” he added.

While educators get it sorted out, teens are watching and waiting. The systems that have created an unprecedented level of academic stress won’t likely be fixed by the time this current crop of high schoolers graduates, but the first wave of Gen Z wants justice for the next. And they know how it goes.

“That's usually a go-to for people in power, for politicians: ‘Oh, this is an issue the community can fix. This is an issue that the citizen can fix.’ And just, historically speaking, especially with schools and education, like, no, you made this policy and these structures and these models to benefit this group specifically and not benefit the rest of them,” Zaida said.

“So this is on people in power, people who have a say over education to fix.”

Colorado Public Radio reporter Jenny Brundin contributed reporting to this story.