Kevin Priola wants to talk about the challenges of dealing with a teen with a heavy vaping habit. The Republican state senator knows first-hand that “it can hit any family.”

“Tell your kids everything you want them to know before they're 13, ‘cause after 13 they won't listen to you,” he said.

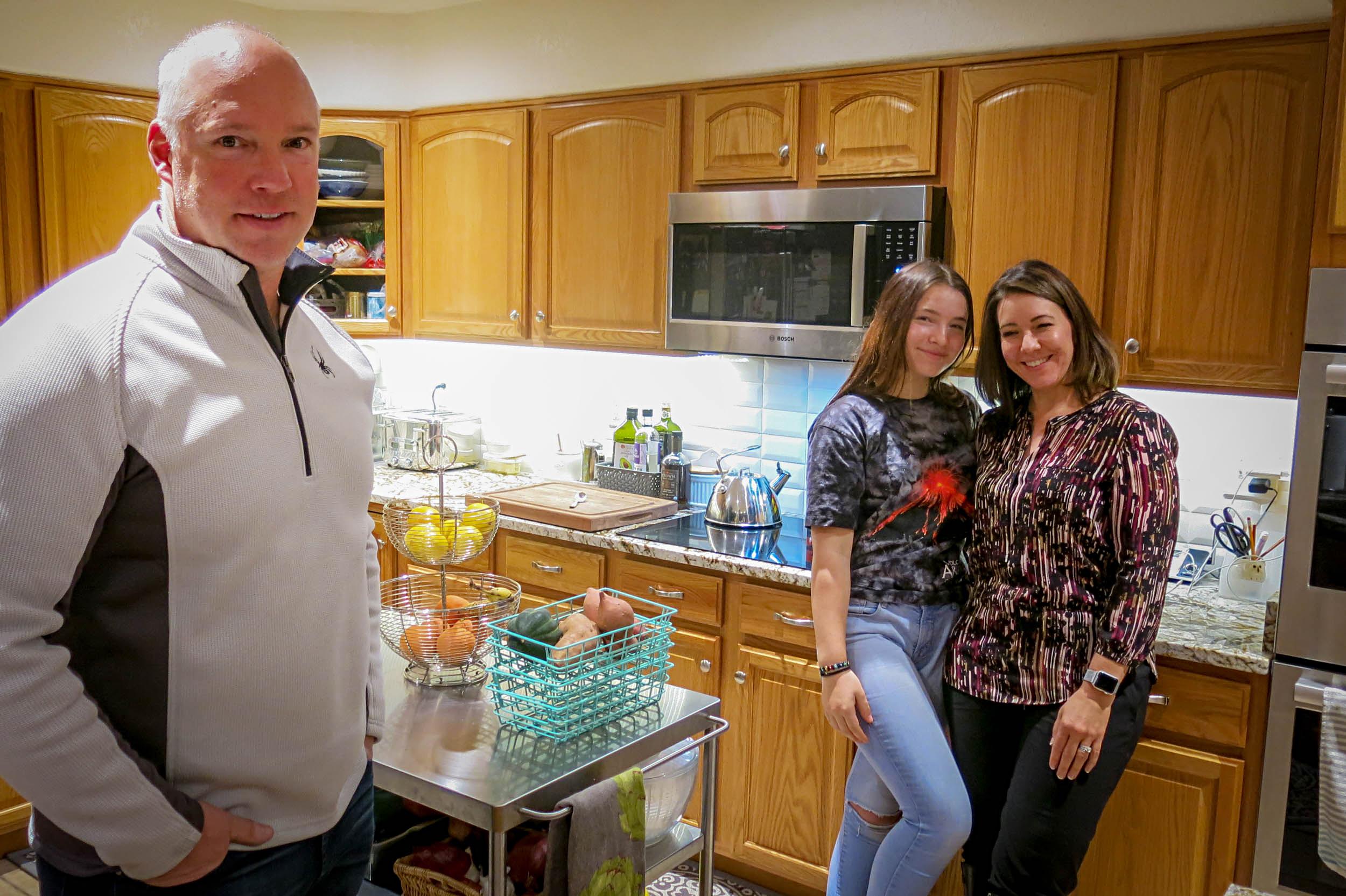

Sitting at the kitchen table of his Henderson home alongside his wife Michelle, he has a cylindrical vape device in his hand. The dad of four took it from his 17-year-old son a couple of years ago. His view of the larger, often spirited, vaping debate is shaped by his experience at home.

“We're of the age and demographics of we’re in the belly of the beast. We have children that are at the age, or they're experimenting,” Priola said.

A moderate himself, Priola represents a swing district in Adams County, where he works in commercial real estate. Many of his Republican colleagues have older children and even grandchildren, while many on the other side of the aisle have younger children or none at all. His family of teens leaves him right in the middle, so he’ll play a key role in crafting vaping bills in a Senate where Democrats enjoy a slim advantage.

Now that Congress has voted to ban the sale of tobacco and e-cigarettes to anyone under 21, Colorado will likely look for other ways to tackle its nation-leading teen vaping rate. The Trump administration has retreated on a full flavor ban. Instead, it decided to allow menthol, the most popular flavor with teens who vape, and tobacco, to remain on the market.

The Priolas’ trouble started when their son was 14. The couple asked that CPR News not use their son’s first name.

“He was having some physical stress from athletics,” said Michelle, a longtime elementary school teacher. “I think some social stress, peer pressure, just trying to get along with kids. Social media was adding a lot of stress,” she said.

They had thought sports — their son wrestled and played football, hockey and baseball — might immunize him to the risky behaviors teens are prone to. Growing up, Michelle thought of kids who experimented with substances as being those who were more on the fringe. They generally weren’t the athletes.

“I see a shift now where athletes are dabbling in these things,” she said. “But they're able to do it without anyone really detecting and figuring it out. So they're pretty sneaky about it.”

Neither parent is a smoker, so they didn’t know what to look for. Plus, vaping devices and pods are designed to be small, easy to hide and hard to detect or smell. They soon, however, started to find signs of vape gear “hidden in places in his room and his backpack, pillowcases, [and] Kleenex boxes,” Michelle said. “I started getting really clever about where to look.”

The new technology makes it harder to know what’s going on versus when they grew up. Back then, a white paper cigarette signaled only tobacco. But today?

“In this day and age, you don't know if it has nicotine and tobacco or if it has really strong, potent marijuana,” Priola said. “You don't know.”

With their son, the Priolas say they tried everything they could think of to help him quit — including nicotine patches and gums, and taking away privileges, like driving. They’re worried and had seen the research which suggests teens who vape are much more likely to go on to use conventional cigarettes.

“It was obvious he was addicted to it,” Priola said. “He would say he could give it up, but he couldn't give it up.”

“He's got really active parents who love him and support him and are on this journey with him,” said Michelle. “And yet we can't get him to stop.”

Bremma, the oldest of the family’s three daughters, said her brother was a more social, carefree and joyous person before he started to vape. She tried to help him quit, and they bonded through that. Bremma teared up as she described how it didn’t work. How he started to vape again.

“When I caught him or my parents caught him, I'd be like, ‘really, you're doing this again?’ It hurt,” she said. “Because I thought I made him see how bad it would be for him. And also he's my brother and I don't want to see him get hurt.”

Michelle Priola called it a vulnerable experience. Even the parents of their son’s friends were reluctant to talk about the rough seas their kids swim in.

“It's a very shameful place for parents,” she said. “I felt very alone in this journey, because people I would talk to would shut me down. They did not want to discuss it.”

For his part, as a lawmaker, Kevin Priola has tried to bridge the gap between the two parties when it comes to teen vaping. He joined Democrats in sponsoring a measure that passed in the last session to ban vaping in most indoor public places.

He remains skeptical about an idea some Democrats favor: raising tobacco taxes. He thinks too much of government is funded by fees and worries that high taxes could create a black market. But he’s open to considering an idea some Republicans oppose: a flavor ban.

For him, thoughtful policies are needed “when stories of kids dying of new diseases are popping up and junior high students with vape pens.” It’s also his hope that lawmakers can work to educate the public about the rise in teen vaping and to find solutions.

In 2019, the urgency of the issue was heightened after dozens of people died and thousands more were hospitalized with vaping-related illnesses. There are 12 recorded cases in Colorado alone. In 10 of those cases, patients were hospitalized.

Before the start of the new year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a total of 2,561 cases in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and two U.S. territories. Fifty-five deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and D.C. Health officials have linked an additive, vitamin E acetate, to many of the deadly cases.

Despite the Priola’s best efforts their son still vapes. Outside of the Capitol, there’s one more thing they can do to fight the stigma.

“The only reason I'm willing to speak about it publicly, because it is so painful, is to prevent and help other parents avoid the same problems with their children,” Michelle said.

_