The year is 2025.

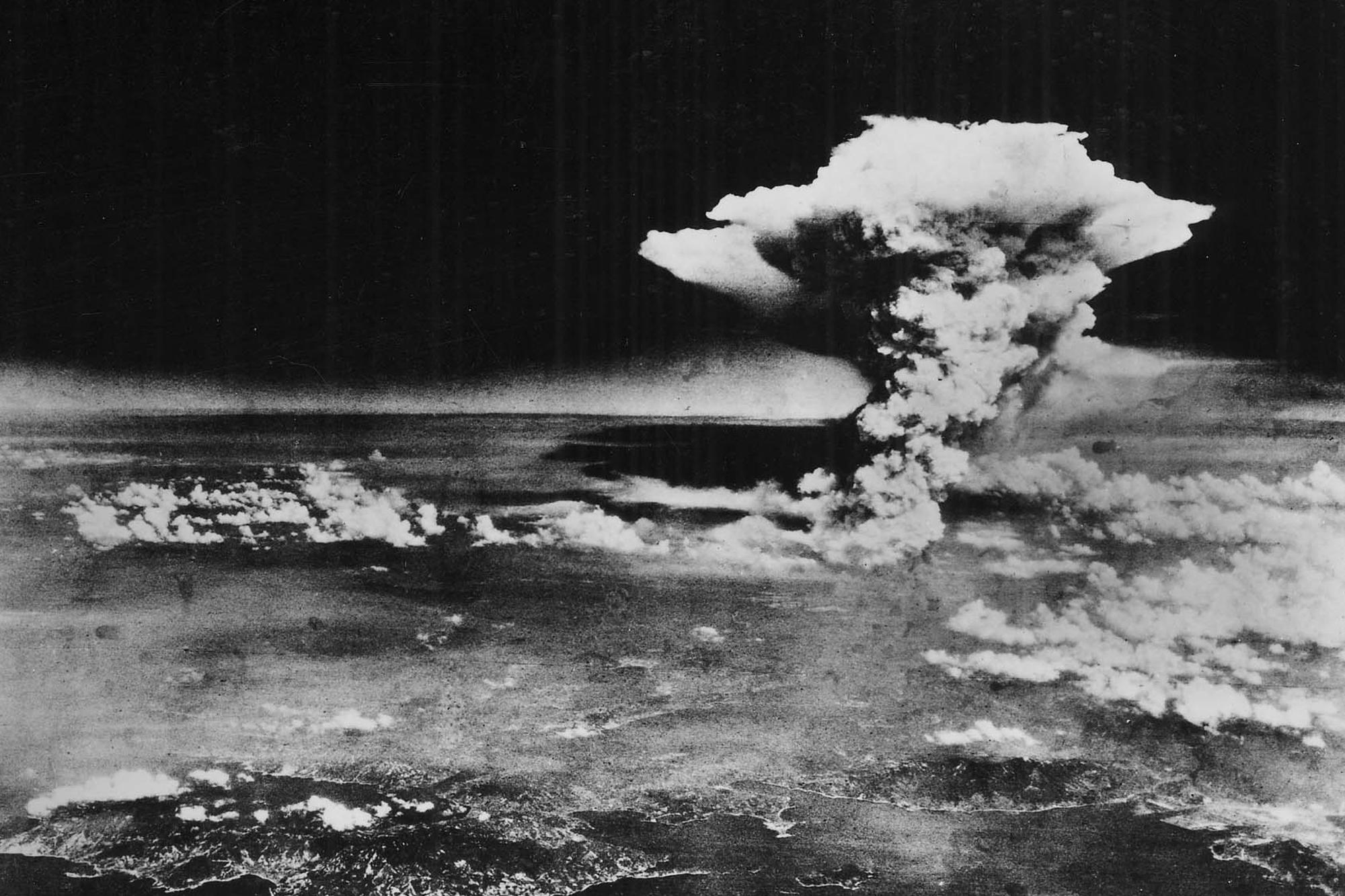

On every TV and radio, reporters recap the events that led to the disaster. It began when terrorists attacked the Indian parliament weeks earlier. The country responded by sending tanks across the border with Pakistan, which attempted to deter the invasion by detonating a tactical nuclear weapon in its own territory.

Panic and miscommunication follow. The world watches in horror as hundreds of atomic weapons destroy cities in both countries, killing as many as 125 million people. And yet, when the dust settles, it appears humanity has avoided a full-scale apocalypse. No other countries enter the war. Most of the world’s nuclear arsenal remains untouched.

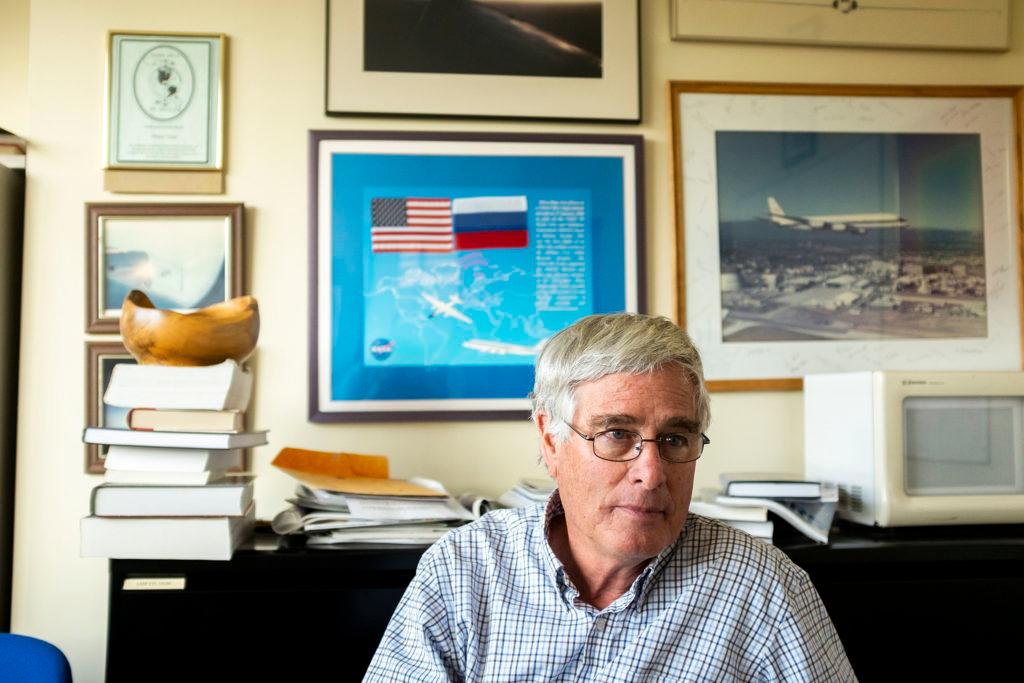

This is the scenario Brian Toon, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, imagines in a study published in Science Advances last October. The work attempts to revive a Cold War nightmare for the 21st century.

As a new arms race heats up, Toon wants to warn the world of nuclear winter — again.

In the 1980s, Toon was among a group of scientists who first theorized about the frigid planet that might remain after a full-scale nuclear conflict. His new work suggests even regional war could refrigerate the climate.

In the latest study, the make-believe exchange between India and Pakistan creates a “nuclear fall” instead of a “nuclear winter,” meaning temperatures rise above freezing during the summer. Toon isn’t sure that distinction matters all that much, though.

“It’s scary,” he said. “It could potentially end global civilization as we know it.”

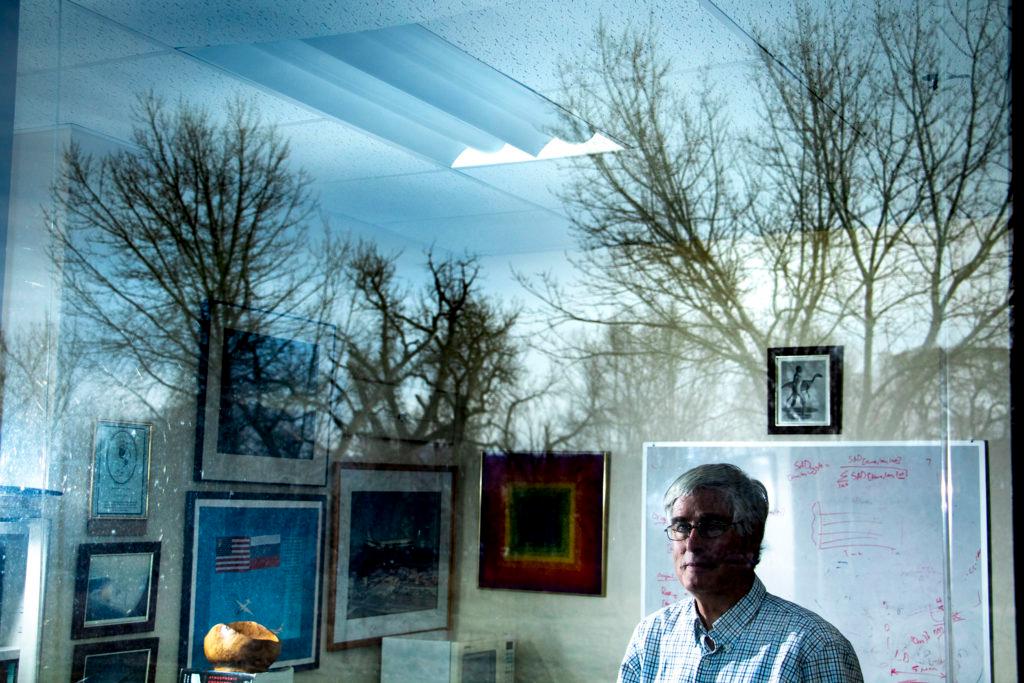

The walls of Toon's sunlit office at the CU Boulder Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics are decorated with reminders of his other contributions to climate science. There are photographs of planes he rode to help discover the ozone hole. There’s a certificate memorializing his piece of a Nobel Peace Prize, which he earned in 2007 for his work on the UN’s International Panel on Climate Change.

Evidence of his work on nuclear winter is harder to come by.

“I hate working on this problem,” he said. “I don't want to think about all those people potentially getting killed.”

Toon said he works on nuclear winter because it’s his job as a scientist. Whether or not the conclusions are political, he has said he has a duty to warn the public if his research reveals unknown — or unheeded — dangers. Such a discovery seemed less likely early in his career. As a young scientist, he focused mainly on otherworldy problems, like Martian dust storms and the atmosphere of Venus.

But that changed after scientists revealed a far earlier planetary disaster.

In 1980, physicist Luis Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez suggested an asteroid killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. The impact ignited massive fires across the planet, spreading dust and smoke into the upper atmosphere. The resulting “impact winter” would kill much of the world’s plant and animal life.

Toon and other scientists decided to examine whether a nuclear war could create a similar effect. At the time, he worked at the NASA Ames Research Center outside San Francisco, which meant he had access to one of the first supercomputers capable of modeling Earth's climate. He had already used it to examine the potential effects of supersonic jets and space shuttle emissions.

“It was just a matter of putting in a different kind of particle,” he said.

Together with researchers Tom Ackerman, Richard Turco and James Pollock, Toon began running nuclear war scenarios. The results excited and terrified the scientists.

While leaders in the U.S. and Russia believed an all-out war could be winnable, or at least survivable, the computers suggested the exact opposite. An exchange between the two countries could drop global temperatures by 15 to 25 degrees Celsius in the first weeks after the conflict, potentially recreating the conditions that killed the dinosaurs.

This is when Toon decided to enlist the help of legendary astronomer Carl Sagan — his former advisor at Cornell University.

Sagan quickly took on a unique role in the team. Even before the group published their official results in Science, Sagan told millions of Parade Magazine subscribers about the frozen hellscape that could follow a nuclear war. Later, he’d offer interviews, make a documentary and debate the ideas before Congress.

“Carl was one of the best educators in history,” Toon said. “It's unfortunate that we have few scientific spokesmen who are that widely recognized.”

Sagan’s persona helped nuclear winter seize the attention of the public and global leaders. President Ronald Reagan cited its main implication in 1985. “A great many reputable scientists are telling us that such a war could just end up in no victory for anyone because we would wipe out the earth as we know it,” he said.

Two years later, Reagan and U.S.S.R. General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev approved the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The world’s nuclear stockpiles began to decline the same year, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The arms race had come to an end.

“It looked for a while like peace would break out,” remembered Toon. “And sure, I think we contributed to that.”

About 30 years later, Toon said he received a phone call from a reporter. Tensions between India and Pakistan were on the rise once again. The journalist wanted to know if a war between the two countries could trigger a nuclear winter.

Toon said it probably wouldn’t.

“I felt very guilty about that because I didn’t even really know how many weapons they had,” he said.

Toon decided to start reexamining the climatic effects of regional nuclear wars. In 2017, after struggling to gain government funding, Toon and other scientists won a $3 million grant from the Open Philanthropy Project to revisit the science of nuclear winter.

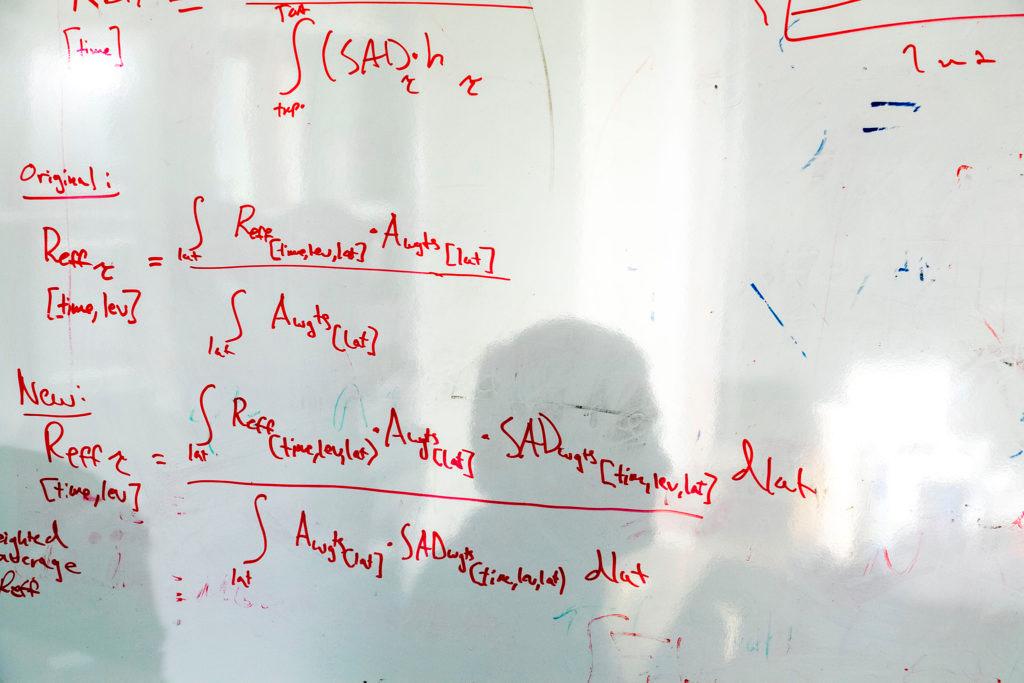

Modern climate models have allowed him to predict the aftermath of a nuclear war in far higher resolution.

According to his latest study, the potential conflict between India and Pakistan could spark massive firestorms in hundreds of cities. The conflagrations would lift tons of soot into the upper atmosphere, beyond the reach of weather systems.

Today, this possibility isn’t as theoretical as it was decades earlier. A recent study of 2017 forest fires in British Columbia discovered the smoke created giant storm clouds, which funneled soot into the upper atmosphere.

Toon predicts a similar process would occur after his theoretical war. Smoke from burning cities would reach the stratosphere and blanket the planet, spreading over Colorado within weeks. He estimates the visible haze would block about a third of the normal sunlight from reaching the ground. Average temperatures would drop by up to 5 degrees Celsius. Global precipitation would decrease by as much as 30 percent.

Strangest of all would be the sunburns. While the world is colder and dimmer, the smoke would burn up the ozone layer, allowing a barrage of ultraviolet light to reach the surface. The combination of cold and radiation would cause massive declines in global crop production.

The latest research has generated no shortage of headlines. “A Nuclear War Between India and Pakistan Could Lead to a Mini-Nuclear Winter,” wrote Vox. “Even a Small Nuclear War Could Trigger a Global Apocalypse,” wrote Wired. While Toon appreciated the press, he said larger outlets have largely failed to cover the threat.

On a recent afternoon, Toon watched a CNN segment with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan. He hoped the interviewer would push Khan about Pakistan’s on-going nuclear build-up.

Instead, the anchor asked Khan about his past relationship with Princess Diana.

For the latest round of nuclear winter research, Toon partnered with Alan Robock, a professor of environmental sciences at Rutgers University. Together, the pair has published studies and op-eds on the climatic effects of atomic weapons, trying to promote both the science and its political implications.

The work hasn’t halted a revived global arms race, though. China, India and Pakistan are all building up their nuclear arsenals according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. North Korea plans to restart tests of nuclear weapons and long-range missiles. The U.S. and Russia backed out of the landmark agreement Reagan and Gorbachev signed after the first nuclear winter studies. And after the U.S. assassination of a top Iranian general, the country has ended its commitment to limit nuclear fuel production.

According to Robock, there’s one big reason new predictions of nuclear winter haven’t stopped the trend.

“Carl Sagan isn’t around,” he said.

In 2014, Robock tried to enlist the scientist many see as Sagan’s successor: Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who had then announced plans to revive Sagan’s "Cosmos" series.

In an email, Robock asked Tyson if he might be willing to use the show to promote new research on nuclear aftermath. Tyson declined in a long response Robock shared with CPR News.

While Tyson said he endorsed the latest research, he explained he wouldn’t make it a personal cause since he lacked Sagan’s expertise on the issue. Tyson added he tries not to offer political opinions. As an educator, he said he would rather people make up their own minds from a base of scientifically verified facts.

“Carl took (public) political stands that brought him simultaneously closer to and more distant from influential political leaders,” wrote Tyson. “I've never (publicly) taken a strong political stand, preferring instead to work across the political spectrum, fearing that absence of access leaves one with less influence than access itself.”

Robock found the response disappointing. Tyson understood the threat, but wasn’t willing to use his fame and authority to warn the world. “He could do it if he wanted to,” said Robock. “He has a platform.”

In Boulder, Brian Toon was less concerned about the response. He understood that Tyson, as a scientist and a science communicator, tended to focus on galaxies and the universe rather than specific planetary disasters. Nuclear winter just didn’t fit with his specialty.

“That’s fine,” he said.

For his research to again shift global politics, Toon said it doesn’t need a champion like Sagan or Tyson. While Toon knows he can’t command an audience like his former teacher, he’s not striking out entirely. A 2018 TED Talk Toon gave on nuclear winter has amassed over 3 million views on YouTube.

What Toon believes he lacks is a working model for scientists to influence the public and political leaders.

“It’s not even clear who’s making decisions any more, to some extent,” said Toon. “We have an uninformed public on these issues. I have no idea what Congress knows about them or whether they are even going to bother to think about it. I don’t know.”

Toon blames a variety of factors for the new circumstances. Fewer news outlets have the resources for science reporters. The end of the Cold War has tamped down fears of nuclear war.

Industries have also improved tactics to squash science when it threatens profits.

In the book "Merchants of Doubt," the authors describe how supporters of new missiles program attacked Carl Sagan and the science of nuclear winter in the 1980s. Toon suspects similar tactics have weakened public trust in scientists and warned his colleagues away from politics. He is determined not to do the same.

“That's what I get paid for by the citizens of Colorado,” he said. “And so even though I hate working on this problem, that's my job.”

For almost 40 years, his warning hasn’t changed. Nuclear weapons are too powerful to ever doom a single enemy, according to Toon. If the missiles and bombs take flight, the whole of humanity stands to lose its home to the cold and the dark.