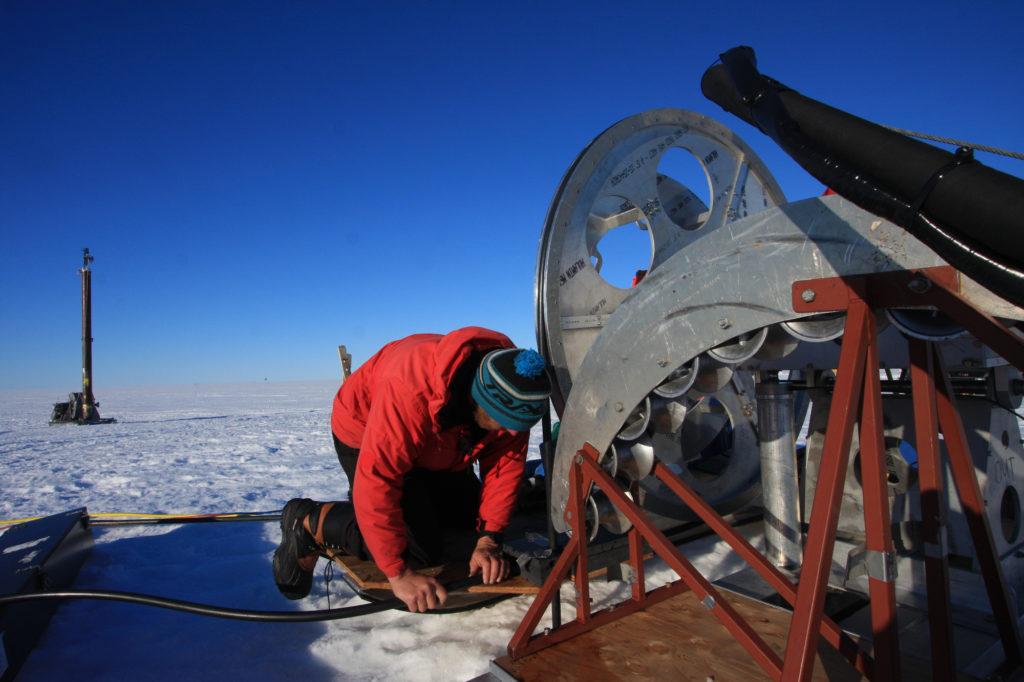

What do you use to bore a hole through a thousand feet of Antarctic ice?

Water, it turns out — hot water under high pressure.

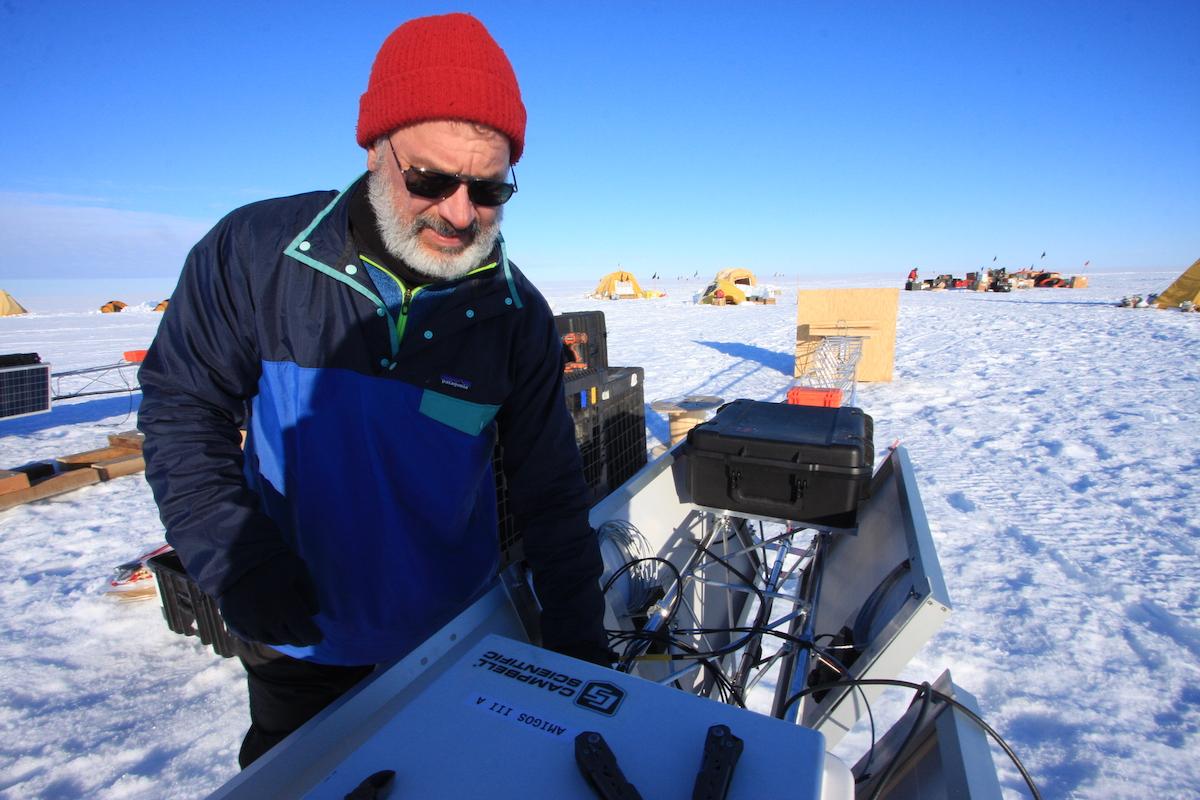

That’s one of the tools scientists, including University of Colorado glaciologist Ted Scambos, are using on the edge of a glacier in the West Antarctic. Scambos is the lead U.S. scientific coordinator for an international group camped at the glacier during the Antarctic summer.

They’re measuring how quickly the ice is melting and how much the water that abuts it is warming. What they learn will help them predict how fast sea levels will rise around the world, a change that puts coastal cities at risk.

“We're hoping that we can give people a better roadmap and either put the brakes on with global warming or be prepared to adapt and modify the infrastructure around the world that is at risk because of higher sea level rise,” Scambos told Colorado Matters by satellite phone from a camp on the glacier.

The overarching question, he said “is how this very large glacier in Antarctica is changing (and) responding to the fact that the ocean system and the atmosphere are changing because of climate warming."

"The Pacific is getting warmer … and that affects the winds around Antarctica, changing how fast they blow and how close they are to the coastline," he said. "That, in turn, affects ocean circulation, creating a cycle that further undermines the glacier and makes it melt more quickly.”

Nine project teams are working on the $50 million, five-year study. Scientists are using ice-penetrating radar and robots to study the history and composition of the ice and its surroundings.

Scambos and his team are focusing, generally, on weather and its impact on the glacier and the ocean. They set up towers on the glacier and instruments in the hole in the ice to measure everything from air temperature to ice thickness and movement. Last week they dropped a fiber optic cable 2,700 feet through the hole in the ice and into the water.

When the teams got to the glacier late last year, it quickly became apparent that the ice was melting even faster than veteran scientists, who’ve been exploring Thwaites for decades, thought. Scambos said that could be seasonal, but the equipment they’ve put in place will return data year-round to increase their understanding of what’s happening.

The scientists are working from the station Camp Cavity, named after the ocean cavity that lies under the glacier. They have one big tent for scientific work, another for dining and eating and several smaller living tents moored to the ice.

The cold temperatures and the pace of outdoor work demand a high-fat diet. A camp blogger recently noted that when a BBC team visited they were given tea made with water from freshly melted snow and full-cream milk powder to add extra calories. Scambos said he’s eating some things he normally wouldn’t.

“We’re putting a lot of olive oil into our food for extra fat, like on rice or in mashed potatoes," he said. "A can of sardines isn’t too appealing to me most of the time, but in Antarctica it sounds great.”