The year isn’t even a month old and fights over health care costs have already ignited Fourth of July-caliber fireworks. With tensions “already pretty high,” Allie Morgan, the director of legislative services for the non-partisan Colorado Health Institute, said there’s one thing you can take to the bank.

“Hospitals versus the state is going to be one of the headlines, if not the headline of the [legislative] session.”

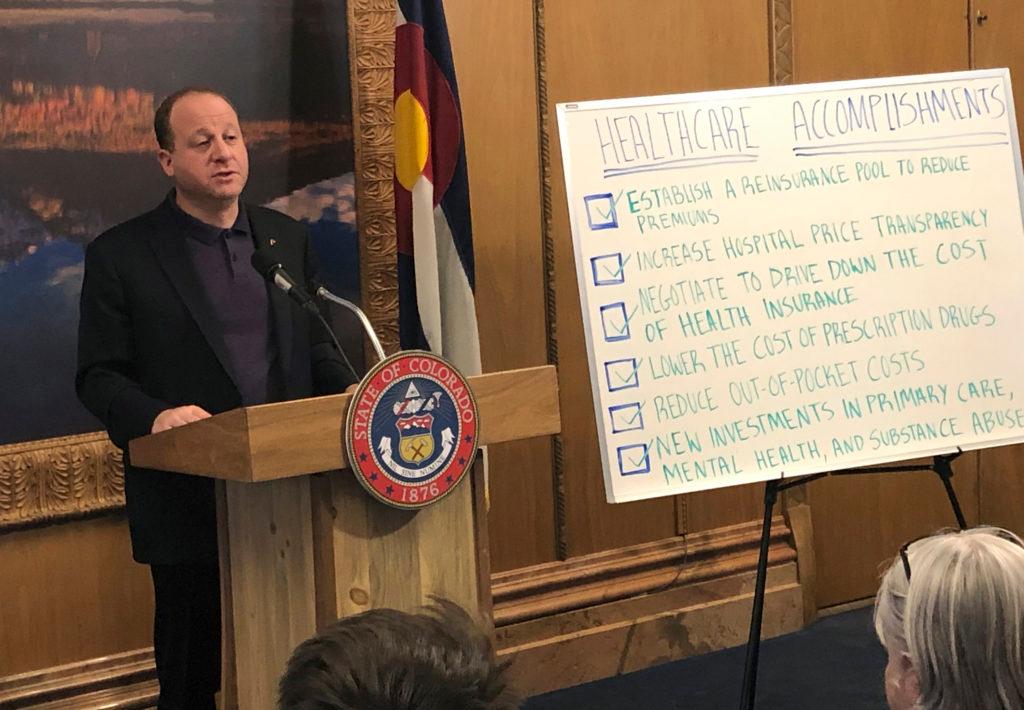

Democratic Gov. Jared Polis has tangled with hospitals for months over several ambitious new programs and proposals — and how to pay for them. In his State of the State address, the governor sharply criticized hospitals over high profits as the state’s health care costs continue to rise unabated. Polis said Front Range hospitals made more than $2 billion in 2018 and he accused them of “already using those profits from overcharging patients” to run ads against any potential legislation for a public option.

From day 1, the administration has pursued health care reforms as a key way to “save families money.”

Just a few days later, the powerful Colorado Hospital Association filed suit against the Polis administration over payments to the fund that pays for Colorado’s reinsurance program. The program is the centerpiece of the governor’s claim to lower insurance premiums. The very next day Polis told CPR’s Colorado Matters that Coloradans are being “ripped off” by the health care industry. He added that a public insurance option could help cut costs.

And that was all in the first two weeks of lawmakers being back to work at the Capitol.

Here are the fronts where lawmakers, the governor and the health care industry will do battle in 2020.

The Public Option

The recommendation for a public option came in November. When the plan was unveiled, Kim Bimestefer, the head of the state’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing agency, and Insurance Commissioner Michael Conway, said the plan could save consumers as much as 9 to 18 percent — potentially thousands of dollars annually for the typical person or family.

The funny thing was, it wasn’t a public option of the sort popularized by Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Their plans would let people opt to buy into a public insurance plan like Medicare, hence “Medicare-for-All.”

Colorado’s edition, still just a draft, is described by administration leaders as a “state option.” And rather than cut out private insurers, which is what insurers fear about an expanded government system, it enlarges their role.

At first, the plan would only be for Coloradans who purchase health insurance themselves. The state would require private insurers already offering plans on the individual market to offer a state-crafted plan. Coverage would start in 2022.

Supporters say it involves several strategies that will cut down consumer costs. It’d limit hospital charges. It’d increase the amount insurance companies spend caring for patients. It’d pass rebates from drug companies along to consumers. And it’d promote competition, especially in the 22 counties where residents have just one option on the individual market.

The proposal does include some mandates, and that’s where the friction between Polis and the hospitals and insurers came from. Without joining the state effort, ‘pretty please would you join the state option’ would soon become ‘we will require your participation.’

Insurers also don’t like the requirement that says at least two insurers must offer the state option in every Colorado county.

Amanda Massey, executive director of the Colorado Association of Health Plans warned the plan “will result in a one-size-fits-all approach replacing market choice and competition.” She predicted it would likely result in cost increases for the over 50 percent of Coloradans who get health insurance through an employer.

Polis clearly sees high hospital costs as a key driver in the overall surge in health care costs. It’s exactly what he said in his State of the State when he noted that, “Colorado has the second-highest hospital profit margin in the country.”

In recent weeks, a dark-money campaign has aired hundreds of advertisements and sent countless mailers out to Colorado residents. That’s just to stop a bill that doesn’t even exist yet.

The ads are from a group called the Partnership for America, but it’s impossible to determine who is funding them or how much the group is spending. The campaign has spent close to $130,000 on Facebook and broadcast ads in the state, according to disclosures from Facebook and the Federal Communications Commission.

CHA spokesperson Julie Lonborg said the governor “believes that this is being funded locally. I think he’ll be surprised to find out that it may not be. I don’t know which if any of our members may be involved.”

Lawmakers OK’d a public option bill in the last session, but the fight now starts in earnest. They could back the Polis state option plan. The Colorado Hospital Association is expected to offer a number of its own counter-proposals.

“We’re working on alternatives to public option, absolutely,” Lonborg said.

One is a “total cost of care” idea, which would set a goal for spending by the state’s entire health care industry, allowing various entities to try to cut costs within their institutions. Six other states including Oregon, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maryland and Delaware, have similar models.

“We’re looking at everything that’s ever been done in other places,” she said, adding one of these models could save maybe more money than Colorado’s state option. Hospitals view this path as more fair and effective than the state setting rates for care.

Neither side has yet been introduced their proposed legislation.

Meantime, Peter Banko, the president and CEO of Centura Health, one of the state’s largest hospital systems, said he was working to find consensus, both along with the CHA and on his own.

“It's going to take a broad-based coalition to fix health care in Colorado,” he said. Banko noted he and others had been “working behind the scenes” for the last month with other health systems, plans, insurance brokers, the business community and consumer groups “to try to craft an alternative.”

In a Colorado Sun opinion column, Banko said the state’s public option plan was unsustainable, jeopardized access to care and might cause employers to drop health coverage. He told CPR hospitals needed to bring forward their own alternative.

“Just saying no is not an option.”

Colorado’s Reinsurance Program

Reinsurance is basically insurance for insurance companies, hence the flashy name. The patients whose care is the priciest account for about half of national health spending. Reinsurance helps cover the costs of those patients.

Lawmakers passed Colorado’s program in the last legislative session and in June the federal government signed off on it.

“The waiver for reinsurance has been granted!” Polis exclaimed in July to loud cheers from the crowd that assembled in the west foyer of the state Capitol. “Rates in Colorado will go down for the first time in history — 18.2 percent average statewide next year.”

The state also projected even bigger savings on premiums, around 33 percent, in high-cost areas like the Western Slope. And statewide insurance premiums on the individual market did fall by an average of 20 percent for 2020.

A major source of revenue for the state’s program, which cost $260 million the first year, is a fee on hospitals. Beyond the hospital’s lawsuit, the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights also seriously complicates funding for the program.

State revenue caps limit how much money the government can bring in annually. When the reinsurance program was crafted, Polis and lawmakers aimed for it to be classified as an “enterprise,” which under state law makes it exempt from the limits.

That status was called into question in December by the state’s powerful budget committee. A legislative analysis found the program could add $165 million to the budget. One lawmaker warned that could cause a “cascading effect across the entire budget.” The governor asked lawmakers for more money, $60 million, to pay for the first two-years of the program. Division of Insurance commissioner Michael Conway told the Colorado Sun the program wouldn’t be underfunded without the money and he was confident the state wouldn’t need the extra money.

The question for lawmakers for the 2020 session is whether to extend the program and how to pay for it.

The Cost Of Your Prescriptions

At the end of 2019, the state issued a 52-page report that outlined “cost drivers and strategies to address them.” One graph spotlighted a stark reality: “U.S. prices are higher than any other country.”

It blames a lack of transparency and “pricing practices” that don’t benefit Colorado,” anti-competitive efforts and investment by drug companies in marketing and lobbying.

Majority Democrats want several legislative measures. For one, they’ve announced the Colorado Prescription Drug Transparency Act of 2020 (HB20-1160). First, it would provide policymakers with critical data to understand and address factors that drive the cost of prescription drugs. They said it would also provide immediate relief to consumers by ensuring rebates insurance companies get from drug manufacturers are passed along directly to broadly reduce premiums.

Sen Joann Ginal, a Demoratic co-sponsor, said the goal is to get drug companies to lower their prices.

“The system is in need of reform, and Coloradans, like all Americans, already pay among the highest drug prices in the world," she said.

Another bill (SB20-107) directs the state to “collect, analyze, and report” prescription drug manufacturer data. The proposal aims to gather that information about the 20 highest-cost prescription drugs per course of therapy and by volume purchased by state agencies. Once the list is compiled, the state would be able to determine the components of the production process that “drive the price” of prescription drugs. Similar proposals have failed in the past.

Other potential legislation would implement new licensing and regulatory rules for third-party administrators who negotiate prices, called “pharmacy benefit managers.”

Another possible proposal would establish a “prescription drug affordability board,” something the state of Maryland has done. An independent board could be tasked with evaluating expensive drugs and recommending ways to address the costs. That could include “the potential to set upper limits” on what Colorado government agencies would pay for some drugs.

The state will also move ahead with a plan to get the federal green light for the importation of drugs from Canada, where prices are lower. The Trump administration recently took early steps to allow the practice for the first time. Drug companies strongly oppose it and say it would jeopardize the safety of the U.S. drug supply.

Community Purchasing Alliances

Summit County launched a community health care purchasing organization called Peak Health Alliance, the nation’s first. It calls itself a “nonprofit health insurance purchasing cooperative.” The group is made of individuals and employers and negotiates prices directly with doctors and hospitals. That combined purchase power gives the group the ability to drive a “harder bargain” with local providers, as the Colorado Health Institute explains.

The Alliance doesn’t push private carriers out of the market. Instead, it takes their place in negotiating with hospitals. CHI’s analysis found the collaborative’s financial transparency may make it more difficult for carriers and providers to blame the other for high premiums.

CHA’s Lonborg said hospitals support the community health alliance concept and have been “integral” in the creation of other examples, like The Community Care Alliance on the Western Slope.

“We do believe that these models need to be truly community based and they must be voluntary to be effective,” Lonborg said.

Colorado's mountain communities have long suffered with some of the country’s most expensive health insurance premiums, driven partially by relatively high health costs in general.

The community purchasing alliance is viewed as a promising way to combat the trend. Along with the state’s reinsurance program, the governor touted the model at an event last fall and said individual plan prices in Summit for 2020 would be down more than 40 percent compared to the year before. He said that would save the typical family of four about $14,000.

Now, the alliance is expanding to other counties in southwest Colorado. Though no bill has yet been filed to boost the concept, Polis said the model is “one we want to replicate across the state.” He also gave Peak Health Alliance a shout out at his annual State of the State address.

Still, since the concept is so new, the next horizon is seeing how the purchasing alliance model works out in other communities.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to accurately reflect when public option coverage would start.