“People with disabilities are reasonable."

That's what Regan Linton, the artistic director of Phamaly Theatre Company, told a room full of creative types Monday night.

“We are not all out there — and I say we because I identify as a person with a disability — to sue you because you f-ed up," she said.

Linton was speaking at an event called “Immerse in Access,” co-presented and produced by Immersive Denver and Denver Center for the Performing Arts’ Off-Center arm with the hope of giving a nudge to immersive art creators to think about how they can design more accessible shows and exhibitions. Linton's theatre company is a performance group that casts artists who identify as having a disability.

“We are all deviants,” she continued. “And I don’t necessarily mean legal behavior, but we all deviate from the norm. Every single person in this room deviates from the norm in some way. I think what society has done is that when someone deviates a little bit further … those are the people we deem as having disabilities.”

She told everyone in the room that this is an opportunity to welcome people, who have likely been made to feel less than, and “make them feel significant.”

“And when you make people feel significant, then a lot of this stuff, you’re already past it,” Linton said.

While there are, of course, the “legal perspective or an obligatory perspective,” of accessibility, Linton said there’s also a huge opportunity by looking at this from a creative perspective.

“One of the brilliant things about immersive experiences and the work that you all do, is that you’re already coming up with new and different ways of doing things,” she said. “You actually end up being trailblazers.”

The presentations also included DCPA’s executive director of equity and organization culture Lydia Garcia, who encouraged attendees to “invert the model of thinking about disability and about what we do in our everyday practice,” referencing the social rather than the medical model of disability.

“The social model distinguishes between impairment and disability, which it ascribes to social limitations,” Garica said. “For example, if I need a wheelchair to be able to navigate the world and I come across a place that is only accessible by stairs, the wheelchair is a part of my physical experience in the world, however, I am disabled by the lack of a ramp or only being confronted by stairs.”

DCPA theater services manager Carol Krueger addressed the law, how “it’s a lot of vague and it’s outlined more and more by the lawsuits that come through.”

“Right, our goal is don’t get sued,” Krueger said, adding the but that “the true ultimate goal should be [Ronald Mace’s Universal Design], and everyone is welcome at all times at all things. We’ll get there, but it takes these steps and historical examples.”

Patrick Mueller, artistic director of Control Group Productions and a producer of an apocalyptic bus immersive experience slated for this summer, let the audience take his event and dissect all of its accessibility obstacles. There’s the bus first of all, which presently is an old school bus without a lift. Performances occur on the bus, as well as off the bus, and there’s about a mile of walking. There are also loud sounds at various points in the show, moments of physical touch and limited access to bathrooms.

“We realize our work is not for everyone, but anyone who wants to engage it, we want to work with them to engage it,” Mueller said. “Our goal is to … create, wherever we can, policies that serve as broad access as possible.”

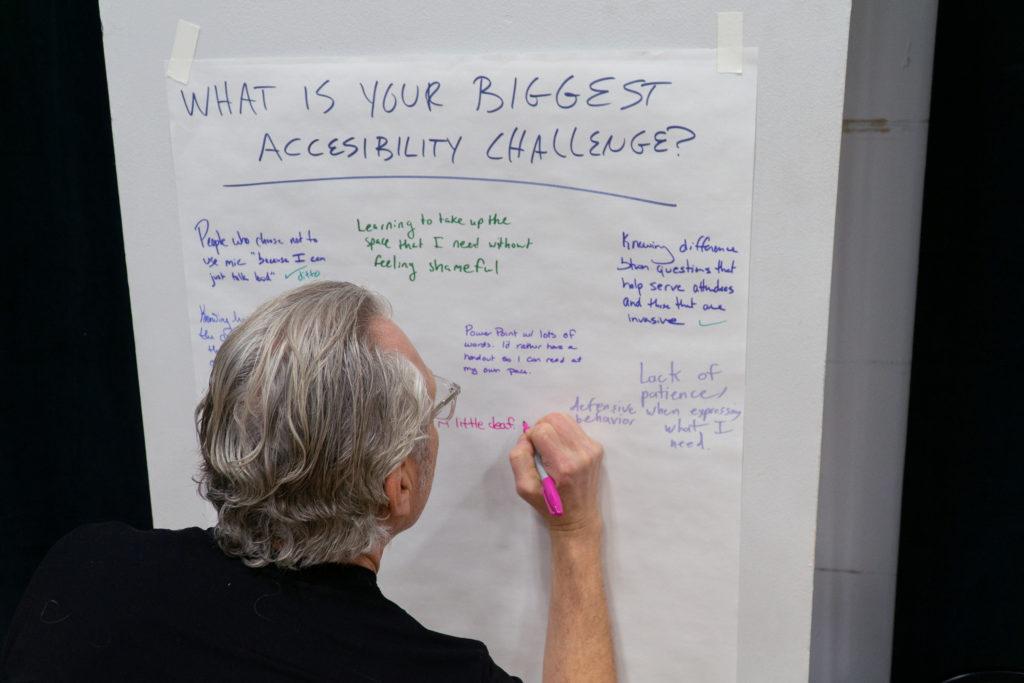

Attendees at Monday night’s event shared their ideas on how Mueller could make the show more accessible. What about an alternate way for people to enjoy the on-bus performances, like a video, if they aren’t able to travel on the bus, or using colored wristbands to indicate when an audience member is uncomfortable with physical touch.

Immersive Denver will make some of these ideas, as well as the presentations and additional resources, available online.

One of the final thoughts of the night came from Brenda Mosby, who said creators could save a lot of time and money if they simply include people with disabilities right from the beginning, evoking the anti-oppression mantra: “Nothing about us without us.”