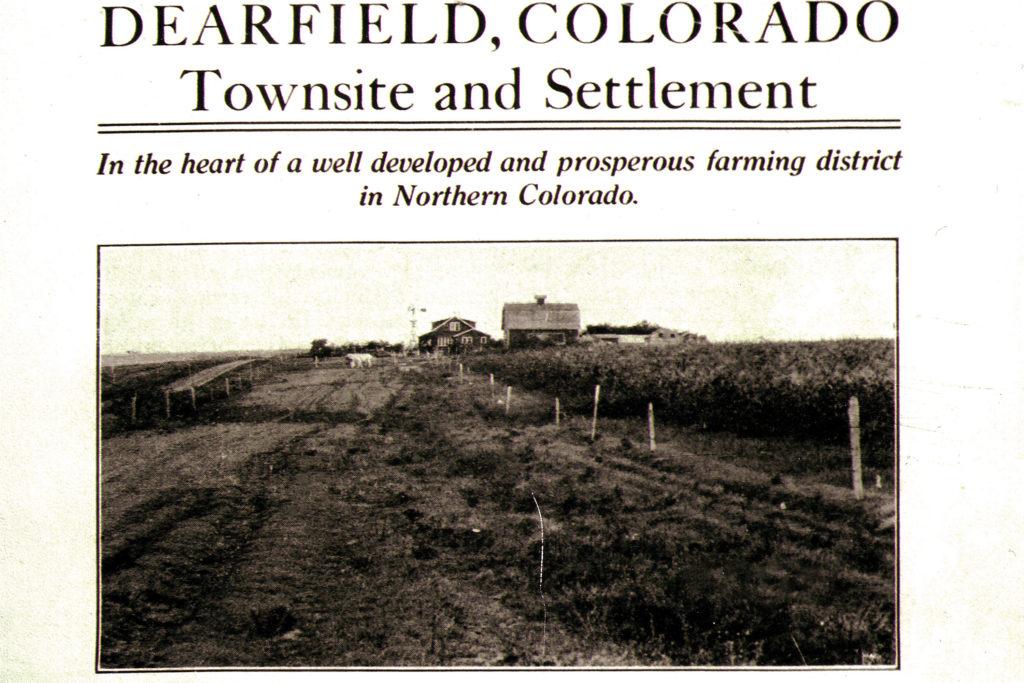

The town of Dearfield, Colorado is a relic now, just a few sagging buildings at a wide spot on the Eastern Plains noted by a nondescript sign on a nearby highway.

But in the early 1900s, it was a thriving community of 300 African Americans, founded with the dream of prosperity as a haven from the discrimination of the day.

Dearfield was even given that name because the land the residents homesteaded was so dear to them.

“People were very hopeful, and they really felt like they could get away from oppression,” said Terry Nelson of Denver’s Blair Caldwell African-American Research Library. “They really felt like Dearfield had potential.”

Nelson is one of several experts featured in “Remnants of a Dream: The Story of Dearfield, Colorado,” a new documentary that chronicles life in the town during the community's most active years, roughly from 1915 to 1920.

The film comes as the chance of preserving the historic site is renewed.

In 1999, Dearfield made the state’s list of “most endangered places,” compiled by Colorado Preservation Inc. A homebuilding company currently owns the townsite and has announced plans to build there.

But now, negotiations are underway for a land swap that would allow construction on the outskirts while saving the more historic area. With those talks underway Colorado Preservation has tweaked the "endangered" status to designate the area as “in progress.”

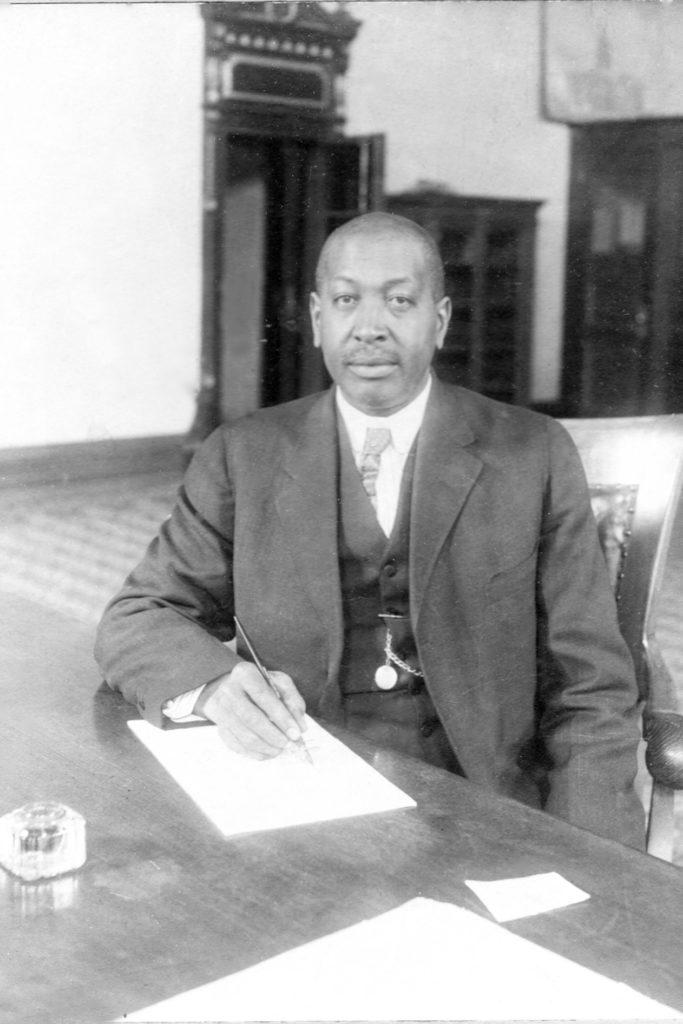

The settlement’s founder, Oliver Toussaint Jackson, adopted the ideas of one of the leading Black intellectuals of the time, Booker T. Washington, who touted a “back to the land” movement that would give Black people property ownership and self-sufficiency.

“Jackson believed that a generation beyond Emancipation … it was time to develop industrial businesses that would provide employment opportunities,” "Remnants" director Charles Nuckolls said.

So Jackson moved to Colorado from Cleveland, driven by “the promise of the American West,” Nuckolls said. Before creating Dearfield, Jackson settled in Boulder as a caterer and restaurant owner and got involved in Democratic politics — a controversial choice at the time, when most Black people were still aligned with the Republican party of Abraham Lincoln.

His political work got Jackson connected to Democratic Gov. John Shafroth, who hired him for what was then a prestigious job as a messenger who delivered confidential documents. Jackson went on to serve six Colorado governors, traveling back and forth to Denver.

In 1910, Jackson founded Dearfield. While he continued his career in politics, Jackson's wife ran a gas station and restaurant in the town.

For a few years, the town flourished.

“There were fairs that would be held in Dearfield, and the governor would come out and award prizes for the most-prized fruits and vegetables grown or the best livestock or cattle,” Nuckolls said. “There were picnics and fishing parties and dancing. There were churches, a missionary society. Dearfield was a thriving community.”

But it was difficult to eke out a living on the dry, windy plains. The farms had no irrigation. Drought after drought struck, driving many away. Before long, the area was part of the Dust Bowl and the community collapsed.

"In 1910, one can only imagine how hard it would be to live there," Nuckolls said. "The people who tried, they were among the most determined people you could find because they wanted to create a better life for themselves and for their children.”