So you’ve got 30 seventh graders in front of you. But something’s off today. One announces that today’s lesson “sucks.” Two shut their hoodies so tight only their noses show. One kid has her head on the desk. Another two are playing Fortnite on the sly. One just gets up and walks out of the room.

Here’s a little known secret: There are times when teachers are so angry or frustrated or bewildered by their hormonally-charged students, the only thing they want to do is act the age of their students. Maybe roll their eyes, raise their voice, say something sarcastic. And when a teacher loses it, the stress in the whole classroom goes up.

Chronically stressed teachers mean stressed kids — classrooms full of kids with higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol, according to one study. Significant numbers of teachers also experience secondary traumatic stress.

The job of a teacher is unrelenting. Most teachers work between 60 and 80 hours a week.

“Teachers are ‘on’ from the moment they walk in the door to the moment they leave, making instructional choices, classroom management choices, getting ready for the next day, adjusting for their lessons,” said Katrina Fernandez with the Adams 12 Five Star District northwest of Denver. “It's a nonstop occupation. If you don't have good self-care practices, it can be a lot to manage within a day.”

But here’s the problem: Not a lot of teachers feel they can ask for help.

“Teachers feel like they've always got to get it right and sometimes we don't even know what ‘it’ is and they feel like they can't make mistakes or people are going to be yelling at them, parents are going to get mad at them,” said Rosalind Wiseman, co-founder of Cultures of Dignity, which encourages communities to shift the way they think about children and teens’ emotional and physical wellbeing.

“What we’re asking teachers to do is really extraordinary and they need support and help and expert advice,” Wiseman said.

Enter “Owning Up,” a social and emotional curriculum authored by Wiseman in collaboration with children and teens. Lots of schools experiment with curricula to teach kids social and emotional skills. But what tends to happen is, teachers are thrown in front of a group of middle schoolers and it’s assumed they know what to do. “Owning Up” is distinctive in that it starts with training teachers, helping them learn to identify and manage their own emotions.

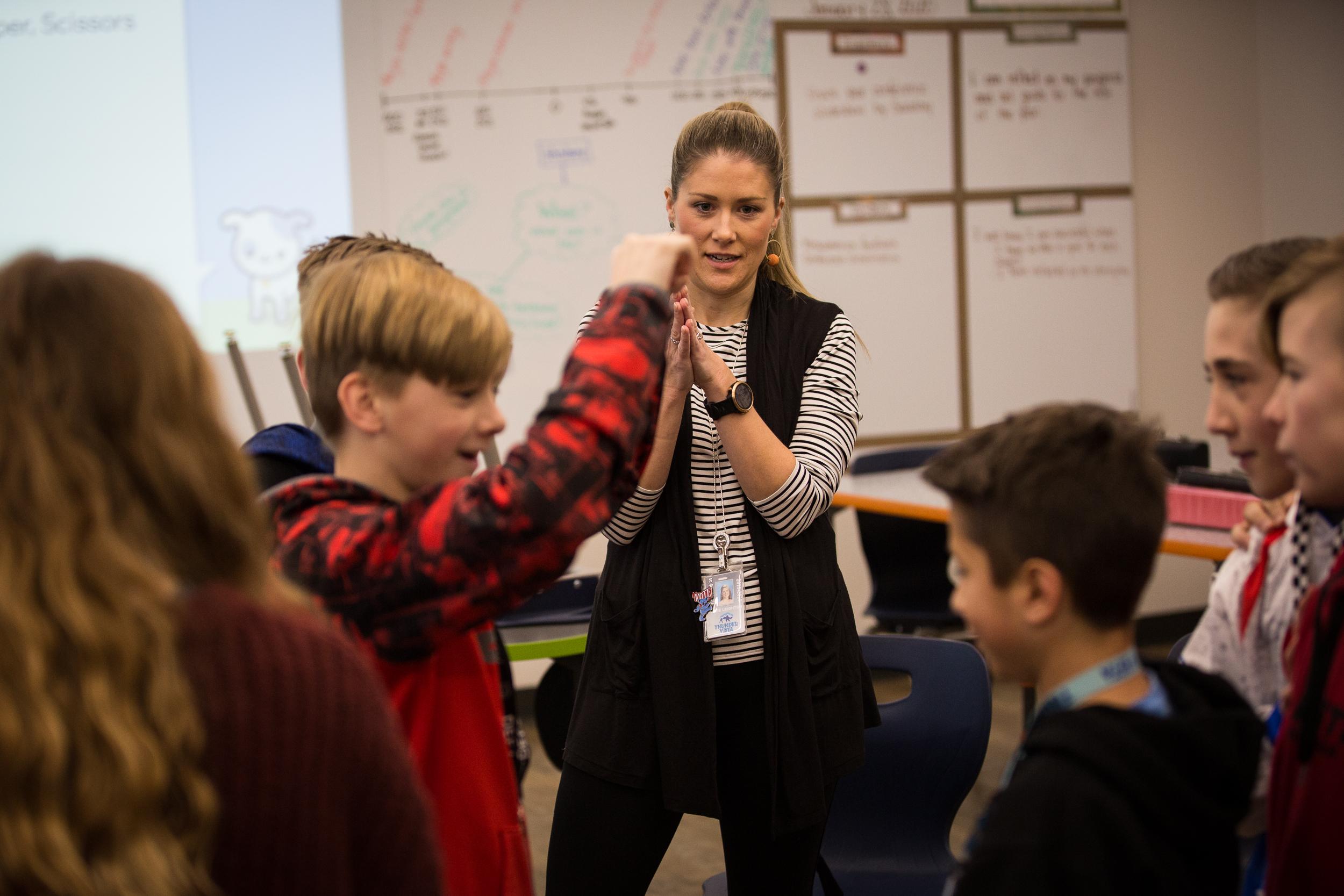

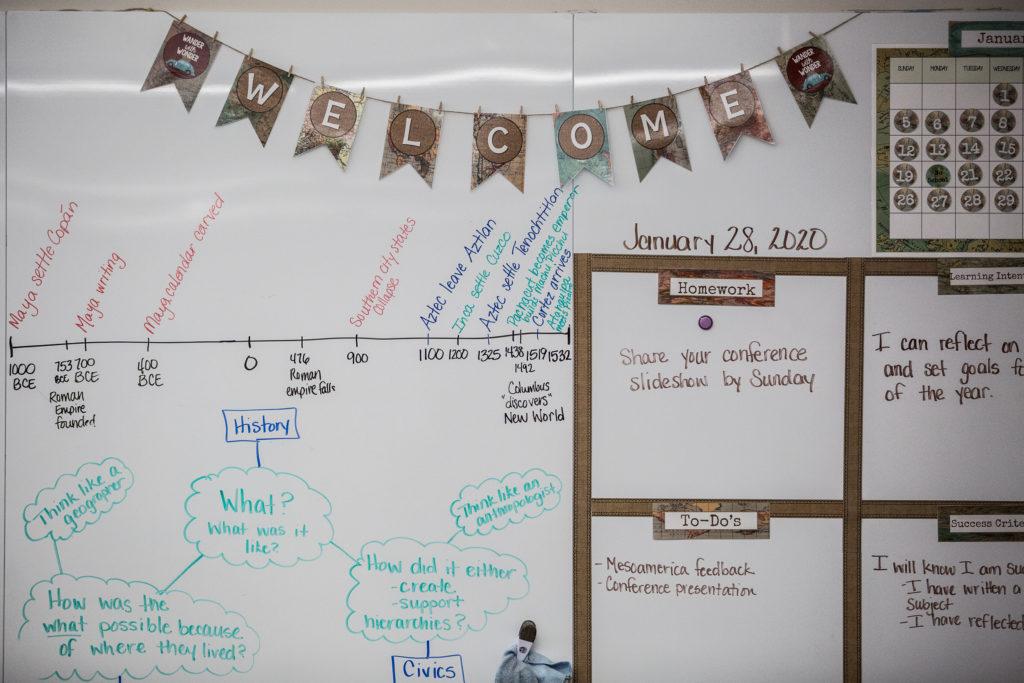

On a recent weekday Wiseman, who is based in Boulder, is training a roomful of teachers at Thunder Vista P-8 in Broomfield. They’re working from the Owning Up curriculum, talking about when teachers have a fraught relationship with a student.

Wiseman tells the teachers that when students are resistant or defiant, teachers may feel embarrassed, maybe even a little paranoid that their authority is being undermined. There is an inclination to say, “‘I am the teacher, you must respect me!’” she said. That’s common.

Teachers in the workshop review how not to resort to demanding respect and instead learn how to probe more deeply and how to create a culture of dignity in classrooms and with parents. Respect, says Wiseman, is a problematic concept for teens because they correlate it with obedience and compliance no matter how the other person is treating them. The group discusses how to stay calm with angry parents and shift the conversation to working together to help the child.

They talk about what makes them lose their cool in the classroom and ways to take care of themselves emotionally, mentally, and physically.

“They have to be attuned to their feelings and emotions and be able to articulate that to a classroom full of middle school kids or elementary school kids,” the district’s Katrina Fernandez said. “And when teachers start to feel overwhelmed and stressed, that can definitely seep into classroom culture.”

“It’s learning how to say to kids, ‘I'm feeling really stressed out right now for whatever reason. How about everyone open their books, you're going to read for five minutes. I'm going to get myself back in a really good place so we can move on,’” principal Teresa Benallo said.

It’s about building relationships with students “and caring about them and they know that you care about them. Kids will do anything for you when you've established that," Bernallo said.

Teachers do exercises with each other — which they’ll eventually do with their students. The idea is to bring the language of emotions and feelings front and center into the classroom. It’s a chance, Fernandez says, for kids to reflect on what’s happening in their inner lives, practice new skills, and then follow up.

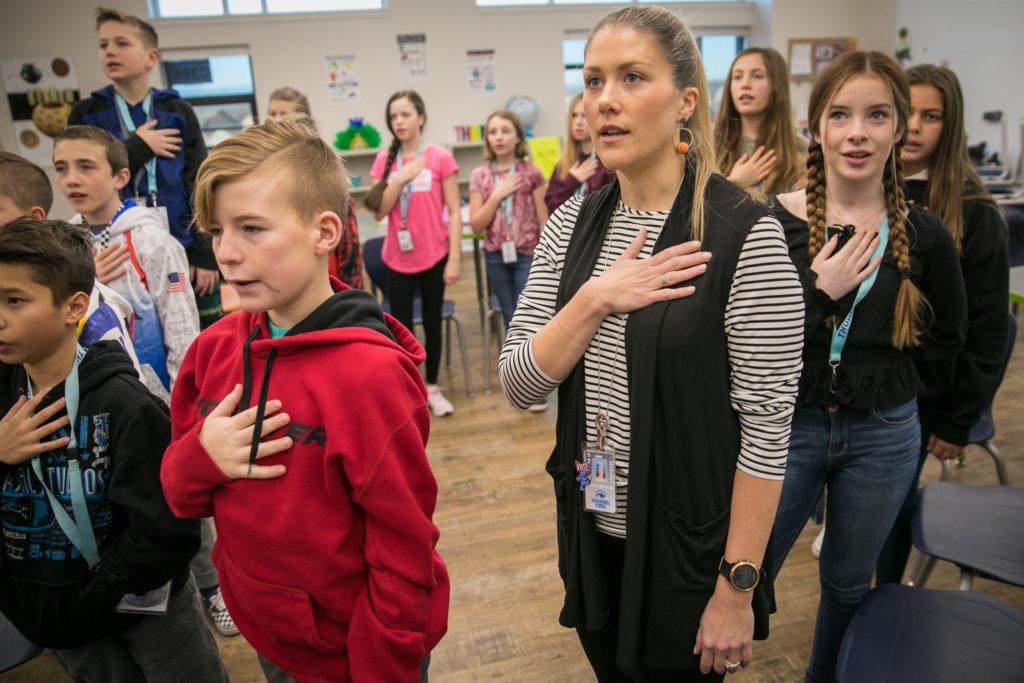

Katie Leighton greets each sixth-grader individually as they file into her classroom one Tuesday morning.

That lets her know she sees them and values their presence. She transitions quickly into an Owning Up lesson.

Half the class is instructed to go into the hallway. She instructs the other half in the classroom to talk to their hallway partners when they return — to talk for two whole minutes about a pet they have or wish they had.

One girl starts off excitedly, telling her listening partner that she wants a dog, a Pomeranian-Shih Tzu mix.

“I love Pomeranians. I would want it to be fluffy,” she tells her partner, who is nodding and smiling.

But at about the 30 second mark, the partner suddenly tunes out and looks away, bored. In fact, that’s happening all around the class.

The Pomeranian fangirl looks kind of uncomfortable. Her two minutes aren't up. Her voice gets tentative, halting and quiet. She tries in vain to engage her partner, to get her interested again.

At two minutes, Leighton asks the kids what the talkers noticed about their listening partners.

“They got quiet and wanted to go to sleep,” says one kid.

Then Leighton reveals her secret instructions to the ‘listening” partners in the hallway before they came back in: they were told to stop listening at the 30 second mark. They were supposed to turn away from their partners.

Leighton asked the listeners and speakers how it felt. Some boys say that happens all the time, so they just turn around and do the same thing. The girls don’t think it happens that often. But the kids agree, the experience was uncomfortable and confusing. They felt awkward. Kids talk about the difference between hearing and really listening to someone, how not to tune somebody out, and how to react when someone does that to you.

The bell is starting to ring — there’s just enough time for Leighton to lead her students through a “triangle” breath exercise. It’s a simple relaxation technique for kids. They breath in for three counts (they can mentally trace one side of a triangle), hold the breath for three counts, and exhale for three counts. It calms them as they head to their first academic class of the day.

The students seem to tune in easily to the feelings generated by the exercise.

If you need help, dial 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also reach the Colorado Crisis Services hotline at 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat.

Owning Up is partially written by kids.

Owning Up author Rosalind Wiseman said kids chose the topics like how to give and get advice, when are kids really joking, what happens if you’re slighted by a friend, why and what do you share on social media, and of course, “crushes, rejection and heartbreak,’” Wiseman laughs, adding, “we let them title the sessions!”

Kids even edit the curriculum.

“I see the editors’ notes all over it. Like, 'This is stupid, this is unrealistic. You have to get rid of this,’” Wiseman said.

“If we want to address the anxiety and the depression that young people are experiencing, we have to ask them what is going on with them. We can't lecture them and tell them what is going on with them and why they're feeling anxious or depressed or what is going on in social media, we actually have to listen to them first.”

Wiseman says students often push teachers to the brink.

Identifying those moments and modeling for students how they feel is the next step, she said.

“It’s okay to have a place where you admit that, acknowledge that to yourself because if you don't, then you're going to take it out on that kid inadvertently in other ways. And that's not professional and that's not acceptable.”

Teachers like Leighton learn how to model for students what they’re feeling — acknowledging when they’re stressed — or wrong.

“I will go to the student and apologize,” she said. “And I think that that's really powerful, when an adult owns something that they've made a mistake with and apologizes to a kid. I think that really empowers them to do it themselves and to feel seen and like they belong."

She’s changed her approach, for example, when a student tries to get under her skin, like when they walk into class and notice they’ll be preparing speeches that day and say, “speeches suck.” Leighton said she’s learned to “not pick that up, but instead to say, ‘Oh, tell me more about that.'"

"So then it's validating them, and not engaging with them in a way that puts them off or creates an argument," she said.

Social-emotional learning, Leighton said, happens in very direct moments throughout the day when she first greets each kid individually as they walk into the classroom or when a new lesson gets really hard, “stopping and saying to her students, ‘This is hard.'"

"'And so if you're feeling that this is hard, that's okay’, because then they can say, ‘Oh, this is normal. I can lean into this instead of running away from it," she said.

Leighton has gotten better at reading body language, following up with a student who later reveals he’s feeling overwhelmingly stressed about a project, so she can talk to his teachers and make accommodations. She’s noticed her students are more relaxed with each other and quiet kids feel safe to talk.

She got a note from one of her students recently. It read: “Thank you for saying that this is a safe space. It makes me feel comfortable to open up. And when kids feel safe and when they feel like they belong, it reduces that stress and it opens them up to learning.”