When Abel Antonio Chavez was growing up as the son of undocumented parents in the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood of Denver, he was already acquiring the know-how and skills that eventually would lead him to become a global force for creating healthier communities.

Back then, Chavez and his dad would search the neighborhood’s alleyways for discarded items that they could repair and sell at flea markets. It was a matter of economic survival, but it was also a way to cut waste by making discarded things useful again.

Chavez had a natural talent for mechanics, but his father didn’t want tough, manual work to define his son’s future. So, he gave Chavez the worst jobs in the heat of summer and the most freezing days of winter. His dad wanted more for him. And that meant obtaining a good education.

He would go on to earn an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Colorado Denver, an MBA at the University of Houston and a Ph.D. in civil and environmental engineering at CU Denver. Chavez became a research fellow at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

He traveled the world — from France to Spain to Colombia to South Korea and Mexico — helping communities track what they produce and consume in terms of “metabolic flows.” That includes things like food, transportation, solid waste and fuels. He directed this research at not just megacities, but also smaller, poorer communities, particularly mountain towns.

Chavez garnered many awards, most recently the Ohtli Award, the highest civil honor awarded by the Mexican government. Ohtli is a Nahuatl word that means path. It is given to honorees who help pave the way for others outside of Mexico. The award puts him in the ranks of other well-known past Ohtli winners in Colorado: former Denver Mayor Federico Pena, Gov. Jared Polis and Polly Baca, the first Hispanic woman elected to the Colorado Senate.

Now Chavez has settled at Western Colorado University in Gunnison, where he’s able to continue his international work on sustainable communities while also following another passion: mentoring underprivileged students. In Gunnison he gets to plug students into that world – students who might otherwise not have a chance at a higher education.

“I had amazing people who guided me, coached me and mentored me. I still do,” Chavez said. “Here at Western I am taking a forward-looking approach to help our students have the same incredible transformational experiences.”

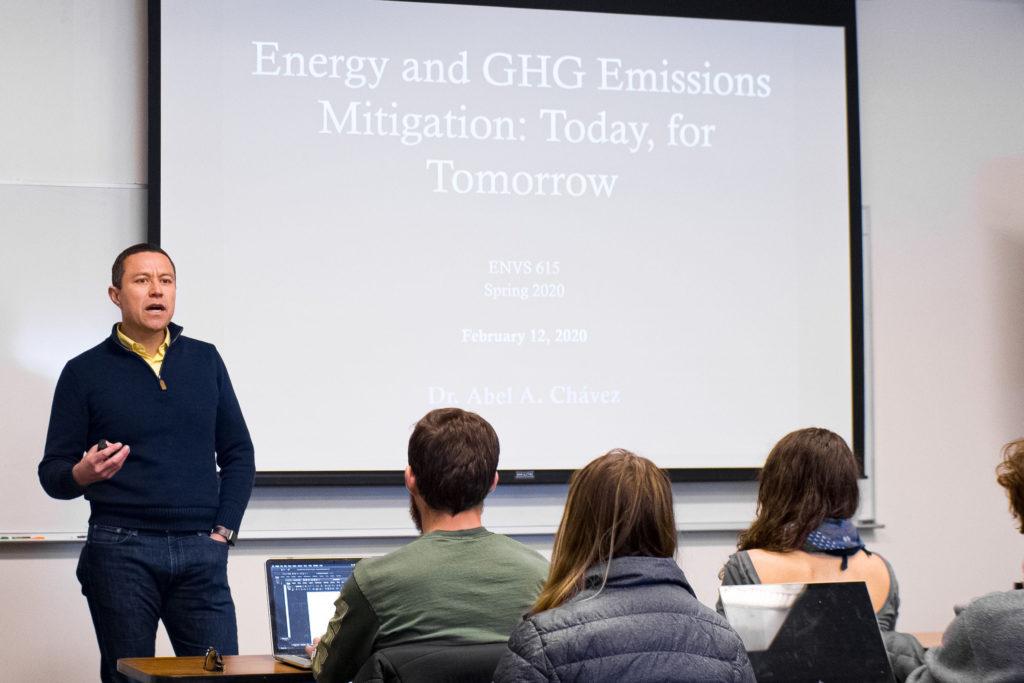

Chavez wears multiple hats at Western. He is the Dean of Graduate Studies, a category that now encompasses one in four students there. He was also recently named Vice President of Student Success and Innovation, which places him in the important role of providing vision and leadership for a growing university and leading an effort to make the institution more inclusive for all students.

He has a helping hand with that through the Colorado Opportunity Scholarship Initiative and IME Becas. The latter is a Mexican government scholarship program to support Mexican students studying in the United States who are in need.

“I’m a big advocate for all youth – any youth – especially those who might not be able to find ways to bridge the financial gap,” Chavez said.

Chavez has found numerous ways to give students real-world experience, from working on sustainability projects close to home in Eagle and Gunnison counties, to traveling to a United Nations headquarters in Rome last fall to create a partnership that will focus on the unique challenges of mountain towns around the world. That U.N. Mountain Partnership mission was spearheaded by John Hausdoerffer, dean of Western’s School of Environment and Sustainability.

For the past six years, the school has offered a master’s degree in environmental management that has served communities with on-the-ground projects across Colorado and the West, and as far as the Himalayas and Costa Rica.

“We are doing incredible work here,” Chavez said. “And that work has global reach.”