Democratic Gov. Jared Polis describes Pueblo as "the heart of Colorado." It’s just a two-hour drive south of the capital city in Denver and holds a unique place in Colorado politics.

It’s a swing county in a historic swing state.

The county is full of the type of independent-minded voters that both political parties want to capture in the November 2020 election. It has been a Democratic region but has backed some Republicans in recent years, including President Donald Trump — a surprise win since Colorado has trended blue and went for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

President Barack Obama won Pueblo County in both of his elections.

Since he’s been in office Polis has visited close to a dozen times and even launched his bid for governor here before the 2018 midterms. He said voters in Pueblo don’t pick a candidate solely based on whether there’s an R or D next to someone’s name. Polis believes his party can make gains in Pueblo by focusing on “bread and butter” issues.

“I certainly ran on my business success as somebody who's created jobs and successful companies,” Polis said. “That’s something that Mike Bloomberg would be able to say that I think would resonate well. There’s probably other things other candidates can say, but people want to see that lived experience. Don't just talk about it. What have you done? How can we know you can produce?”

Pueblo native Jacqueline Riggs is one of those split-ticket voters. She’s a pro-union, pro-public schools Republican who voted for Trump and Polis.

She teaches English and American literature at East High School in Pueblo and has seven children and 21 grandchildren. She may have been born and raised in the community but Riggs said she lived all over the place when her husband served in the U.S. Air Force.

Riggs liked the Democratic governor’s focus on education, but she agrees with the Republican party’s economic message and Trump’s trade policies. She disagrees with Trump on his push for a border wall with Mexico but believes taxpayers shouldn’t foot the bill for people living in the country illegally. She wishes he wouldn’t say everything that comes to his mind.

“Are his personal values like the way he's lived his life, divorce and affairs and some of the things that he's said about women, those are not my values, but his policies are,” Riggs said. “Like, I don’t take it seriously. The rhetoric, banter, in your face politics, I wish he wouldn’t do it as much as he does. Honestly, people hear that stuff and that’s all they hear.”

Most of Riggs’ coworkers are Democrats and she said she’s even lost some friends because she plans to vote for Trump again.

“The feeling that I get from the left is that they really honestly believe that I am immoral because I voted for Trump,” she noted.

But it cuts both ways. Her colleague Tammy Highberger, a special education teacher and strong Trump supporter, said she has trouble remaining friends with Democrats in this political climate. Highberger said she likes the president’s personality, his straightforwardness, his tweets and his tough stance on illegal immigration. She favors a border wall. Highberger added that when it comes to politics, she tries to avoid the topic altogether.

“Only because I right away dislike people because of their political views because I can't understand how they could say the things that they would say, even that Trump is guilty of Russia, Russian collusion,” Highberger said. “So many things that he has accomplished they refuse to give him credit for it. And I disrespect people that can't even do that.”

Not talking about politics is one thing their Democratic colleague Michael Maes agrees with them on. Maes and his wife raised their three children in Pueblo. He backs Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders for the Democratic nomination. He said if Trump wins re-election, he fears for the future of the country.

“I think what he's done to this nation, both within and throughout the world has just been terrible for us,” said Maes, who runs the school’s library. “Whatever you think of his economic policies, that's stuff that can be debated, but how he's handled immigration, how he's handled foreign relations, the obvious corruption. I just think that's unacceptable and it's a slippery slope to start going down no matter what political party you belong to.”

The political inclinations and the everyday experiences of these school teachers are a microcosm of the larger divided electorate.

About half of Pueblo’s residents are Latino and registered Democrats outnumber Republicans. However, Pueblo Democrats have traditionally been more conservative than in other parts of Colorado. In 2013, Pueblo recalled a Democratic state lawmaker over her support of stricter gun laws in the wake of the Aurora theater shooting. Today, part of the county is represented in the state legislature by the most moderate Democrat in the capitol.

“People are just frustrated with the status quo and that’s what gives Trump his power in Pueblo,” said Democratic Rep. Bri Buentello. The area has a higher poverty rate than Colorado as a whole, and the economy is not booming here like it is in other parts of the Front Range.

In 2019, Buentello split with her fellow Democrats on a number of high profile issues. She voted against a so-called red flag gun law, opposed an overhaul of oil and gas regulations and she did not support a bill to give the state's electoral votes to the presidential candidate who wins the national popular vote. In the current legislative session she opposed a measure to replace Columbus Day as a state holiday.

“I didn’t think it was in line with fighting for Colorado jobs,” she said. “I don’t believe stripping Italian heritage is a way to protect that Pueblo heritage.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Pueblo became one of the nation’s manufacturing hubs thanks to its steel mill. It was also the magnet that drew in Italian and other immigrants. The steel crash and recession of the 1980s would later hurt the city economically.

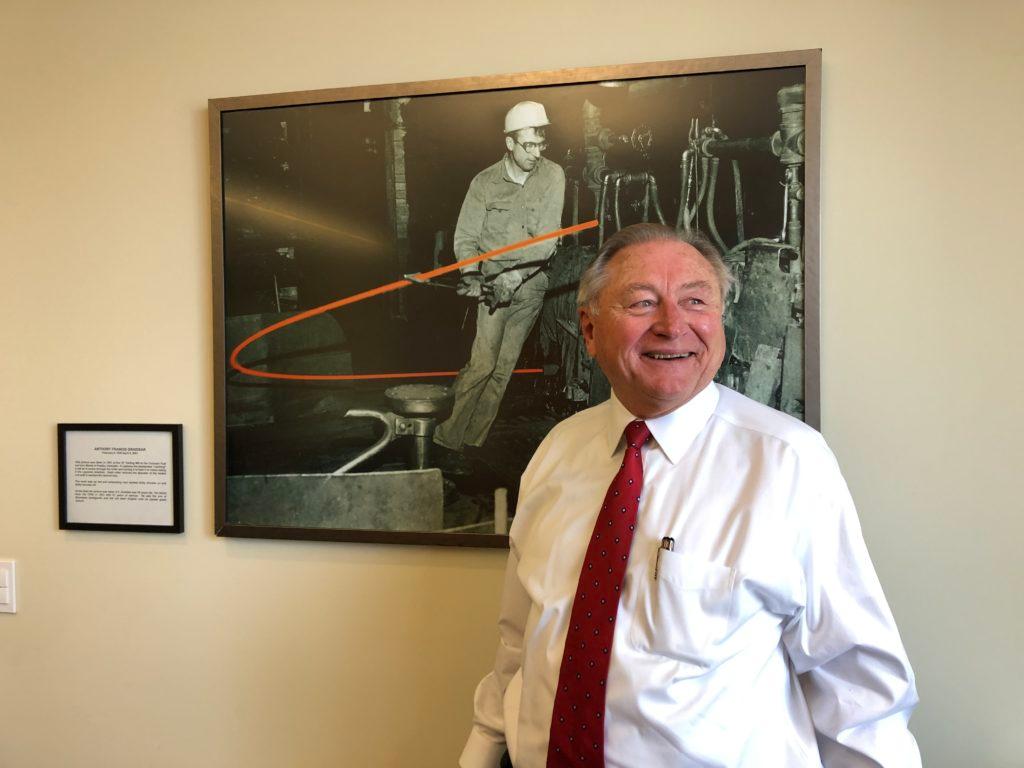

“People came to Pueblo from all over the world to make the steel that built the American West,” said Mayor Nick Gradisar. His own family is part of that heritage. His grandfather was a Slovenian immigrant who worked in the steel mill, Gradisar’s father followed suit. When he became mayor, Gradisar installed a large framed family picture of his father working in the mill. “There were 40 different languages that were spoken at the mill, 24 foreign language newspapers in Pueblo. So Pueblo has that kind of proud history.”

The region still has strong ties to organized labor but as steel jobs continue to decline, the community is working to diversify the economy and expand into areas like renewable energy and marijuana.

Beyond manufacturing, Pueblo is home to the Colorado State Fair and is known for its famous Pueblo chiles. It also has proximity to rivers and outdoor recreation, a draw local officials hope will help attract and retain younger residents who often move away for higher paying jobs.

But over the next eight months, it’ll be the area’s political dynamic that will likely draw the most attention, particularly when it comes to Colorado’s U.S. Senate race.

In 2014, when Republican Sen. Cory Gardner ousted Democratic incumbent Mark Udall, Gardner narrowly lost Pueblo by less than 1 percentage point. Gardner is up for reelection in 2020 and he’s expected to face a tough campaign to try to hold onto his seat.

That makes Pueblo County one of the state’s many political battlegrounds. The city itself only has about 100,000 residents, but in a Senate race that’s expected to be highly competitive, even a relatively small number of votes could mean the difference between winning and losing.