Cinematographer and camera operator Kent Harvey, whose resume includes nearly a dozen Marvel films and Universal flicks like “Everest,” cut his teeth in his home state of Colorado, back in the early 90s.

Projects like the first feature film he ever worked — the slapstick hit “Dumb and Dumber” starring Jim Carrey and Jeff Daniels — plus television series, car commercials, national commercials and cable channel movies kept him very busy. But nearly as quickly as his career took off, things started to slow in Colorado.

“Other states developed incentives which lured work away,” Harvey said. "Other countries lured work away with their incentives, including Canada and New Zealand ... And Colorado really took a big hit. A lot of work left town.”

The passage of Amendment 2 in 1992 didn’t help either. The referendum forbade municipalities from passing anti-discrimination laws to protect LGBTQ people. The New York Times reported that a TV executive told the state film office that “swung the decision away from Colorado.” The Supreme Court later ruled it unconstitutional.

A lot of that work left for places like Louisiana, Georgia and eventually neighboring New Mexico and Utah. Because of their incentives, the bulk of the work never really came back, according to a number of folks in the local film and television industry. These states offer millions, in what are essentially rebates, to lure productions.

In fact, Netflix bought a large studio space in Albuquerque to serve as its U.S. production base because it’s been creating so much content there, series like “Longmire” — based on books by Wyoming author Craig Johnson — “Godless” and the Coen Brothers’ “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.”

The thing is Colorado can’t seem to decide whether it wants to be a hub for filmmaking, even with all the cinematic landscape here.

To invest, or not to invest

The state has put money into incentives to invigorate the local industry. In 2012, new legislation boosted the incentives program to a 20-percent rebate on qualified spending. Today, production companies can recoup some of their expenses so long as at least half of their crew is hired locally and they spend a certain amount in state, depending on whether it’s a Colorado company or an out-of-state group.

Some notable productions have shot in Colorado since the current iteration of the state’s incentives program went into effect. Five million went to Quentin Tarantino’s violent western-esque “The Hateful Eight.” It was filmed in Telluride, and according to the film office, spent about $30 million in the state — a Telluride tire shop ended up being quite the beneficiary of the film crew being in town.

The film office has also claimed that incentive money is what sealed the deal to get Top Chef to film its 15th season here in 2017.

And Kent Harvey was one of about 50 Coloradans who got work on Netflix’s “Our Souls at Night,” an adaptation of the late Colorado author Kent Haruf’s book of the same title. The movie, which starred Robert Redford and Jane Fonda, received about $1.5 million in incentives after filming in Southern Colorado in 2016.

“[It] was a treat to be able to work here locally,” Harvey said. “But these days, that kind of opportunity is really unusual.”

State funding has been inconsistent since it’s subject to legislative debate via the Joint Budget Committee every year. The pot of incentives has yo-yo-ed, with it as high as $5 million one year and as low as $750,000, where it presently stands. A damning audit in 2017, which found that ineligible projects received incentives, nearly spelled its end.

Gov. Jared Polis, whose office declined an interview for this story, has proposed to keep the incentives at that $750,000 mark, despite the fact that the Colorado Office of Film, Television and Media burned through all of that money last year in just a few months and needed a cash infusion from the Strategic Fund, as reported by the Denver Business Journal.

Mitch Bell, VP of physical production with Marvel Studios, said that’s small potatoes compared to programs like New Mexico’s $110 million and Georgia's, which doesn’t have an annual cap.

Bell grew up in Fort Collins and routinely looks up Colorado’s film incentives program to see if anything has changed.

“There's nothing that I would rather do than come film back there,” he said. “The problem, and I think it's with most studios these days, the margins are very thin because DVD sales have bottomed out and streaming is not the same model in terms of profit. So most studios are looking for an incentive.”

Part of the idea with incentives that draw big motion pictures here is that local companies will provide equipment, crew and sound stages. However, as major projects have often passed on Colorado over the last few decades, those resources have diminished — just as content creation on the whole explodes with streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime and now Disney Plus.

An industry on the decline?

Charmaine Calderón-Balcerzak is a period and multicultural hairstylist for film and television. Her IMDb page said she’s worked on films like “The Banker” and the now-in-post-production Aretha Franklin biopic “Respect.” The last film she worked on in Colorado was “Our Souls at Night.” Since then, she’s basically relocated to Atlanta because, as she puts it, that’s where the work is.

She’s held on to her Colorado home, though, because her husband still works here and her kids go to school here.

“I'm just traveling back and forth constantly,” she said.

Calderón-Balcerzak believes the local industry is in “dire need right now.”

The state’s largest film production studio, WestWorks, recently announced it’s closing. Colorado Extras Casting in Englewood has “cast its last project and closed its doors,” according to its website. Other facilities have had to downsize, like Lighting Services Inc., which moved out of its 60,000 square-foot Denver facility in 2012 and now runs shop from a 20,000 square-foot Littleton space. The owner, Ken Seagren, recently told the Denver Business Journal his business has become “almost a hobby now.”

The decline in infrastructure, particularly the lack of large sound stages, is another strike against Colorado in terms of drawing in the big-budget projects, Mitch Bell of Marvel Studios said. He thinks that incentives, in the ballpark of millions, must be “in place first,” because films could land in Colorado for location shoots.

“Otherwise building stages won't do you any good,” Bell said.

Brian Steward, the director of the Colorado Film School at the Community College of Aurora, said it’s disheartening to hear more and more of his students talk about leaving the state.

“They want to go to other markets such as Atlanta, such as New Mexico or even Los Angeles,” Steward said. “I think that's probably due to the fact that they see the resources that are dedicated to film dwindling in our state.”

It’s not just about Hollywood

Many Colorado-based productions and companies get these funds because they also hire and spend locally.

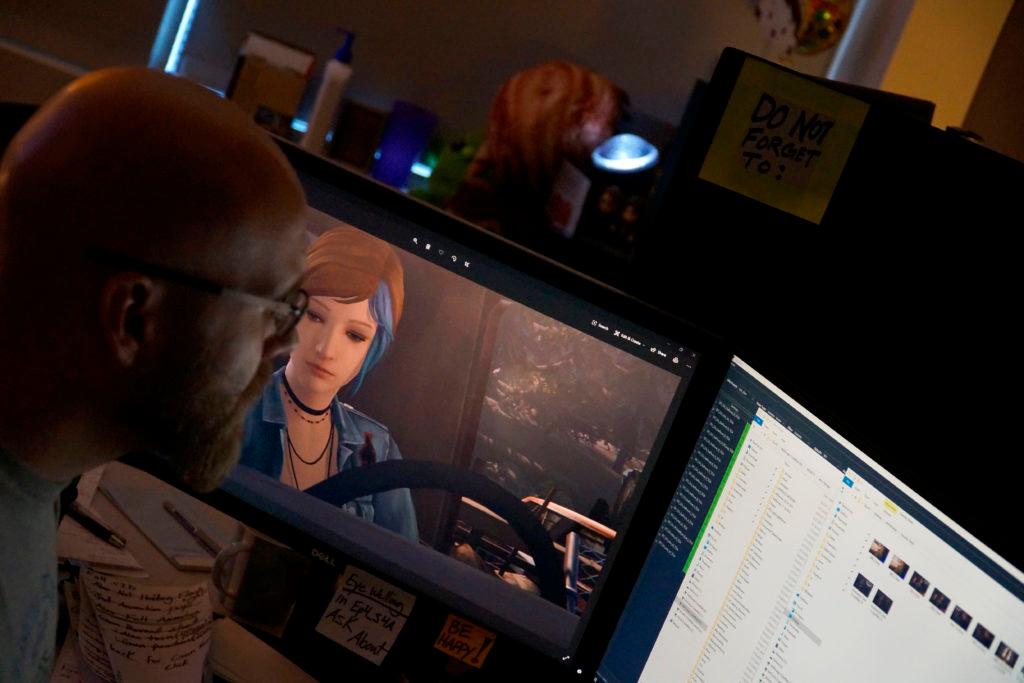

Westminster-based video game developer Deck Nine Games hires local actors, directors, writers, cinematographers, etc. to create narrative-rich, choose-your-own-adventure video games. One of its recently released games, “Life is Strange: Before the Storm,” was nominated for a BAFTA and VGA.

Vice president Jeff Litchford said those funds have been essential in helping the company get contracts with clients from all over the world.

“It's a competitive landscape and this allows us to be more competitive,” Litchford said. “We can also use that money to develop new techniques for our motion capture facility and develop new tools so that the work that we do for our video games is better.”

Deck Nine Games reports that it’s received $1 million in incentives since 2016 and is expecting another $300,000.

One of the actors working in the company’s motion capture studio said with less and less work popping up in Colorado, she’s now got agents in three different states.

Litchford doesn’t want to move the company itself, but if the industry doesn’t get sustainable support, he said they’ll have to consider relocating some of their resources.

“At some point it will reach a level where I can't hire the actors that I need and I can't hire the support staff from this area,” he said. “I might need to close down the motion capture stage here in Colorado and relocate it somewhere where the talent pool exists.”

His concerns echo many others in the industry: if something doesn’t change soon, the fear is that there may not be an industry to save.

Lawmakers might have a fix

State Rep. Leslie Herod, a Denver Democrat, wants to head off a potential death of the industry in Colorado.

“People are filming stories about Colorado in other states,” Herod said. “Why are we allowing those communities and other states to benefit from the investment that comes [from that]?”

She plans to introduce a bill proposing a different way to stimulate the industry, one that’s not subject to annual debates. It’s a wonky thing called transferable tax credits. Basically a media company would get to sell off tax credits when it owes less in state taxes than the credit is worth. Then a Colorado company can buy that credit for its own use. It’s another way for productions to get some of their money back.

The bill, which will also be co-sponsored by Democratic state Sen. Nancy Todd, would cap these annually at $5 million.

Todd told the Denver Business Journal that the credits would be granted just in years in which “state revenue exceeds the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights cap, so as not to take from other priorities during times of budget-cutting.”

Critics of incentivizing the industry in the past have asked why the state should give handouts to Hollywood, especially when things like education, roads and transportation also need funds.

Herod said movies provide work for Coloradans, and bring in people who eat at Colorado restaurants and stay in Colorado hotels.

“This is a great and fun way to invest in local governments in Colorado, specifically rural Colorado,” Herod said. “I think being able to see your town celebrated in film is an exciting thing, but also it brings money into these local communities.”

Democratic State Sen. Dominick Moreno said the challenge in the past has been that there are many things they’re trying to fund, and wonders if this could be a more palpable approach given the possible lack of “political appetite to have direct state appropriations” for the industry.

“I don’t know all the details yet,” Moreno said of the new bill. “So I can’t speak to where I’ll ultimately land on the issue, but I'm open to the conversation.”

Brian Lewandowski, executive director for the University of Colorado Boulder’s Leeds School of Business, poured over 18 years of motion picture and sound recording data from all 50 states, and said it’s clear that “productions chase incentives.”

The data also shows Colorado is not so unique in having a small industry. It falls in with the vast majority of states where film, television and commercial production contribute less than half a percent to overall GDP. Lewandowski said the question for Colorado then becomes about return on investment.

The Leeds School of Business has calculated that every dollar spent by a production company could generate approximately $1.70 in the local economy.

“I think that film incentives are somewhat unique in that you can get activity turned on very quickly by deploying film incentives,” he said.

And that’s what folks in the industry are hoping to communicate to state lawmakers on Friday when they rally at the state Capitol for “Cinema Day,” pleading with their elected officials to turn things around before it’s too late.