South of Manzanola in Colorado's Eastern Plains, there once was a community called The Dry.

Carolyn Sanders, who grew up in nearby Rocky Ford, heard about the town, but never got a clear picture of its history, so she asked Colorado Wonders.

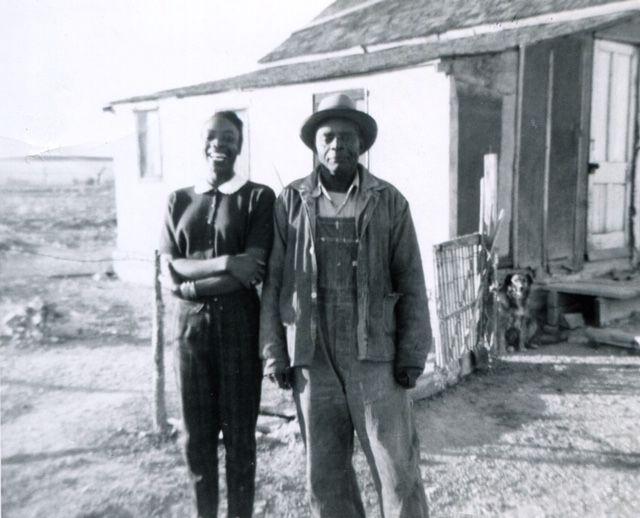

The Dry is an abandoned farming community founded by African-American homesteaders, but it’s still revealing stories. In part, because 85-year-old Alice Craig McDonald, who was born there in 1934, is still around to tell them. And because historical archaeologist Michelle Slaughter, with Alpine Archaeological Consultants, is eager to hear them.

The name says a lot about why The Dry didn’t make it. Black families came to the area in 1917 to grow crops, but irrigation plans failed, the Depression sunk the economy and the Dust Bowl swept away the soil. So most families moved on. But when the town first got its start, it was a tight-knit community.

McDonald’s family joined about 50 families who settled The Dry.

They heard about it from two African American women, sisters Josephine and Lenora Rucker. They worked for a man named George Swink, who was white and had been in the area since the late 1800s. He established what would become Rocky Ford and managed to irrigate the melon crops the town would become famous for. He encouraged the Ruckers to homestead and said he would supply water for irrigation.

“He had told them that they needed to go and find other blacks to come and homestead in Colorado and they could own a piece of land,” McDonald said. “So many of them, the families came from slavery and they came into Missouri and into Kansas and they were working as sharecroppers. So when the sisters came and told them about Colorado, they told them that it was a wonderful place to be and that the soil was rich and just ready for farming. And that's all they knew how to do was farm.”

The settlers would use an expansion of the Homestead Act that granted twice the acreage to people willing to stick it out on marginal land in the West like The Dry.

When the families arrived it certainly didn’t look like rich farmland.

“All that they could see was this flat, dry land,” McDonald said. “And they were quite disheartened when they arrived in Colorado.”

Most of the families built dug-out homes, which McDonald remembers as “warm and cozy in the winter and cool in the summer” with floors swept and packed hard like concrete.

The settlers built a reservoir to store water from the Apishipa River and irrigation ditches that led to the fields.

“They opened the headgates and let the water come down through the canal and irrigated this wheat field, and it was quite a thing,” McDonald said. “Everybody came. All of the people that lived on The Dry gathered to see this first irrigation of this wheat field.”

“And they said, ‘Well, all right, now we're going to be able to farm. We have our irrigation systems in,’ ” she said.

It didn’t last long. Just two years later the earthen dam collapsed after heavy rains, and she said most of the families were too disheartened to rebuild. The settlement dwindled and few remained by the end of the Depression and the Dust Bowl.

McDonald said it was remarkably free of racial tension between blacks and neighboring whites.

“There was no strife and there was no racism,” she said. “The people that came to The Dry depended on the white farmers and they were glad that they had come because they knew they knew how to farm and they knew they were willing to work.”

She describes one incident where her father’s car broke down at night. He began the walk home and saw ahead a bright glow. When he got closer he saw it was a gathering of hooded Klansmen with torches.

“One of them called out ‘Harv, what do you need?’ ” McDonald told Colorado Matters.

Her father explained he was walking home because his car broke down, and she said the Klansman — a friend he knew — said “I’ll pick you up in the morning and take you to your car and get it started. And another one rode up and said, ‘Who is that?’ And he said, “Oh, it's Harv.” And he said, ‘Does he need help?’ And he said, ‘I told him I would help him tomorrow. Not to worry.’ ”

After most of the settlers left The Dry, McDonald’s parents and a few others switched to raising dairy cows, pigs and chickens. McDonald lived in the town through high school. Her grandmother and aunts were the last to live there, up until about 1983.

The Dry never had a townsite; it did have a one-room schoolhouse. McDonald said it got its name because people would explain they lived on the dry land south of Manzanola, and it got shortened to The Dry.

Michelle Slaughter started her archaeological research on The Dry in 2010, with support from History Colorado's State Historical Fund and the University of Denver.

By then, there were only foundations of homes and the schoolhouse was a pile of lumber. McDonald’s family home had stood until 1998. No one was living there at the time and vandals burned it to the ground.

While a great deal has been lost, Slaughter said there has been a lot to learn. McDonald has helped her team understand the lay of the settlement. Where there were stock tanks, where there was a chicken coop or where they had horses and cattle.

McDonald toured the site with Slaughter’s team and was impressed by how they figured things out.

“I found it very fascinating the work that they do, because they were looking for pieces of glass and items that normal people would just walk over,” McDonald said. “But they were picking them up and they were looking at the lay of the land and they were able to determine where the outhouse had been or where the coal bin had been, or whether they were burning wood or burning coal. They were very, very observant and saw many things.”

Slaughter even found a toy Roy Rogers sheriff’s badge on McDonald’s family homesite, that could have belonged to McDonald’s brother.

Slaughter has done extensive research beyond oral histories, checking newspaper accounts, tax records and homestead papers. In one instance, she found that records showed a settler named Noah Smith was married.

“And we were very surprised. . . we didn't find any artifacts related to having a woman in the house. And we were very curious as to why that was,” Slaughter said. “And we asked Alice about it and it turns out that, yes, Noah was married, but his wife was not fond of living out in the middle of nowhere and eventually moved back to Denver. And then Noah divided his time between The Dry and Denver.”

Slaughter finished her grant-funded research on The Dry in 2013, but she wants to do more someday. She is frequently asked to talk about what she has learned. Many plains towns died out during the Depression and Dust Bowl, but The Dry was one of only two black full-time settlements in the state.

The other, Dearfield, 70 miles west of Denver, evolved at about the same time. It had about 700 residents and a townsite that included churches, a restaurant and a post office, but it also was hit hard by the Depression and the Dust Bowl and didn’t last long.

McDonald’s family still has the homestead property on The Dry. Now, as a retired school teacher who lives in Manzanola, she appreciates the beauty of the open land, a place where “you can see for 100 miles.” And she has fond memories of the place it was.

“Now, as far as the homes where, they were some distance apart, but once the people arrived and were there on The Dry, they needed one another and they needed to help one another and they needed to relate to one another. So that brought the closeness of the community,” McDonald said.

Editor's Note: Shanna Lewis produced the audio version of this story for Colorado Matters.

Editors note: This story has been updated to correct Alice McDonald's age, identify Michelle Slaughter's current employer and clarify the provision of the Homestead Act the settlers used.