Temple Aaron in Trinidad has been a part of Randy and Ron Rubin’s life since they were kids. The brothers and their family have been taking care of the synagogue since the 80s.

“It has meant our religious education since we were little boys. One of my most vivid memories is my bar mitzvah,” Ron said. “It was a meaningful moment in time … We were the only Jewish family to have bar mitzvahs there for many many years.”

Randy, who lives about 20 miles south of the temple in Raton, New Mexico, said it has a lot of generational ties for him. He remembers being the only kids running around at one time.

“My parents attended there,” he said. “And my children were bar mitzvahed and bat mitzvahed respectively.”

Temple Aaron is Colorado’s oldest continuously operating synagogue. It has a brick facade all the way around. The building is two stories high with an onion dome on top. Two large wooden, carved doors greet guests in.

In 2016, it all nearly came to an end when Temple Aaron temporarily closed and the Rubins considered selling it. Maintaining the building got to be so expensive after the 2008 economic crash and significant repairs needed to be made. Since then, the community has rallied behind the synagogue with a more robust board and support from across Colorado and New Mexico. People also travel from across the country to see the historic building. But leaders say it still faces challenges.

At its height, in the late 19th Century, Temple Aaron had about 75 families who were part of the regular congregation.

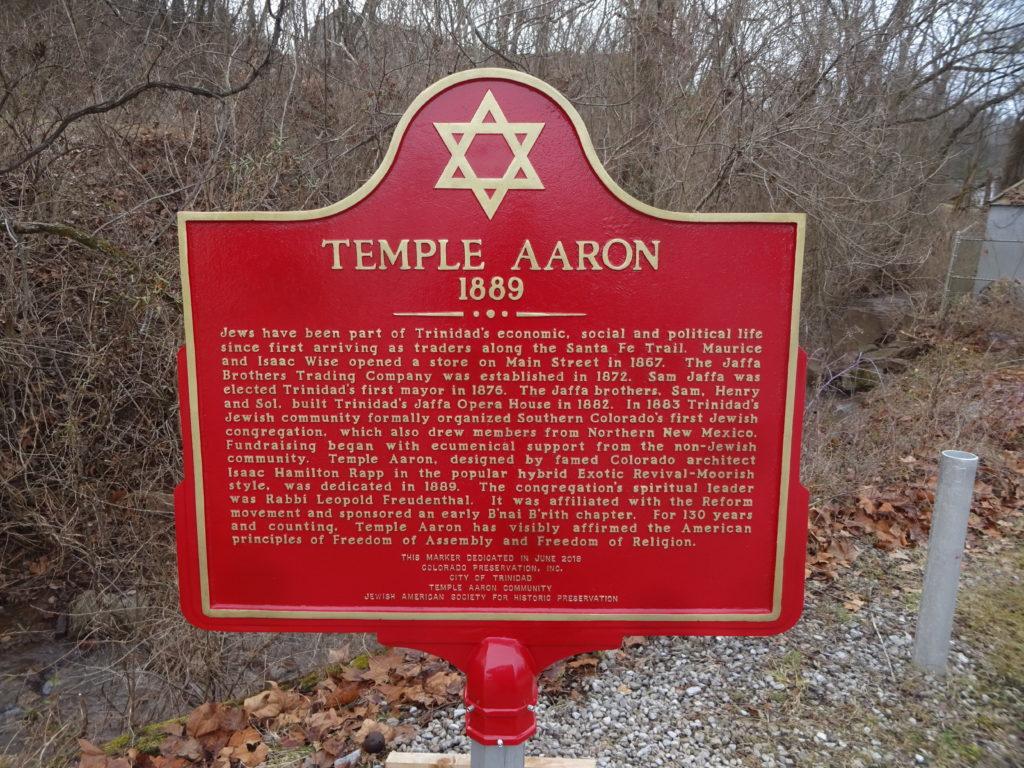

Kim Grant is a temple board member who also directs a Colorado Preservation, Inc. program that works to preserve historic places and archeological sites. He said the temple tells the story of German-Jewish settlers migrating west, particularly across the Sante Fe Trail, and settling in Trinidad.

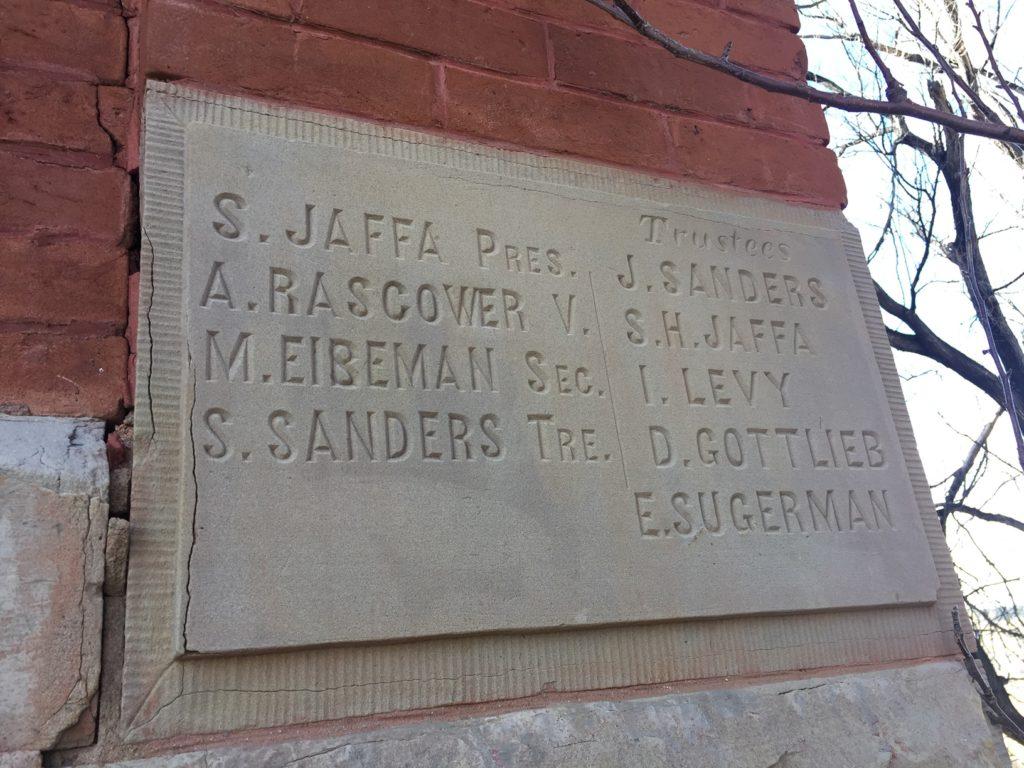

“Some of the leading members of the community, including Sam Jaffa, who was Trinidad's first mayor, were Jewish,” Grant said. “There was a kind of a merchant and professional class of people there that built like the Jaffa Opera House and a number of mercantile stores and businesses there and played a role in the community and its development.”

In 1883, Trinidad’s Jewish community organized a congregation that brought people from around the region — from Raton and Albuquerque, New Mexico, all the way to Pueblo. The temple was built in 1889 and affiliated with the Reform Movement, a Jewish denomination that honors Jewish traditions but acknowledges the religion may change and evolve over time.

European Jews of different persuasions also migrated to Trinidad from Galveston, Texas during the Galveston Movement in the early 1900s, which brought new perspectives to Temple Aaron.

The building was designed by Isaac Hamilton Rapp, who is credited with creating the Santa Fe style of architecture and built over 80 buildings in Trinidad alone, Grant said.

“The temple is one of the most spectacular buildings he did,” Grant said, adding that Temple Emanuel in Denver has a similar style. “They call the exotic revival style architecture with Morrish influences and the big towers with conical shape tops and things like that. So there are a few other examples like that around the United States but Temple Aaron is pretty rare for that kind of thing West of the Mississippi.”

Grant said despite the mix of Jewish identities, the temple continued to practice Reform Judaism. The organ still found inside the temple today is evidence of that.

“It's a reform touch because Orthodox and Conservative didn't have mechanical music, and we do have that. And the organ really kind of has a majestic sound when it's played,” Rubin said. “It's got gold pipe surrounding the workings. They're not functional, but they had a grand touch because they're so large.”

Attendance dwindled over time.

Jewish folks started to move to bigger cities in the late ‘20s, Grant said. By 2008, after the financial crisis, operating costs got to be so expensive that Rubin, his brother and mother — the leaders of the synagogue at the time — decided to sell the building in 2016.

Rubin said they worried about what could happen to the building. Some potential buyers proposed putting offices in the basement. Others thought about turning it into a non-denominational wedding chapel with lodging downstairs. A yoga studio was another suggestion.

“Why don't you all do this? Have you tried this? We've brainstormed ad nauseum,” Rubin said. “We agreed when this all started that it would stay in Jewish hands and be used as a Jewish institution as it had been for 127-125 years.”

When word that Temple Aaron could be sold spread, the Rubin family began to hear from folks all around Colorado who wanted to help save it. They eventually took it off the market and committed to keep it operating.

In 2017, it was added to Colorado’s list of most endangered places. Other preserved spots on the list include railroad depots, ranches and other places of worship.

“That's about the time that I got involved with it,” said Grant, the board member. “We're working to preserve the building and seek National Historic Landmark status for it.”

The board is now made up of people from around Colorado and New Mexico. They celebrated the 130th anniversary of the temple last year and installed a plaque. Rosh Hashanah was held in the fall.

Sherry Knect, a board member from Littleton, said she was surprised by the people who would travel from as far as New York to attend the events. She says they’re drawn because of Temple Aaron’s historical significance but also because they have family ties there.

“People came out of the woodwork and they were telling us how happy they were that we're doing this and we didn't really know all these people were out there,” she said. “It's a special place.”

A fundraiser in February in Denver raised funds for matching grants and to make much-needed repairs to the building. Temple Aaron needs a new boiler, roof, kitchen and ADA-compliant bathrooms, plus funding for its basic operating costs.

“We think we’re on the right track and we’ve had great outreach,” Rubin said. “It's heartwarming, I must say. And this may sound a little maudlin to you, but I'm going to say it. When I walk in there, there's an odor, a smell, a fragrance. To me, it's a fragrance that I remember since I was a child.”