Walter doesn't look like an economic savior.

At the moment, he’s not even a fully exposed skeleton. His bones remain encased in rock and plaster in the basement of Colorado Northwestern Community College in the Moffat County town of Craig, waiting to be freed by students armed with brushes and tiny hammers.

In short, Walter is a fossil, but not just any fossil.

The 74-million-year-old duck-billed dinosaur is at the center of a unique paleontology program. CNCC is one of a few community colleges the federal government has named a legal fossil repository. That has allowed the school to build a program where students seeking associate’s degrees work on real dinosaurs.

“Students get to prep these bones at 100 and 200 level,” said Elizabeth “Liz” Johnson, a science instructor and curator for the repository. “We’ve had PhDs come out with us who have never been in the field before — and they’re being taught by 200 level students.”

The program now faces vast expectations from the surrounding community.

Craig has long relied on coal for jobs and tax revenue. In early 2020, Tri-State Generation and Transmission announced it would close a mine and a power plant in the area by 2030. The news put extra pressure on the community to diversify the economy away from fossil fuels. And fossils, like Walter, are at the top of the list for many community leaders.

The city and county have expressed interest in a small museum connected to the college. The hope is to catch tourists driving along U.S. 40 between Dinosaur National Monument to the west and Rocky Mountain National Park to the east.

“Just the numbers alone that could bring to our community — it’d be a great shot in the arm,” said Craig Mayor Jarrod Ogden.

Northwest Colorado has long been famous for its treasure trove of fossils. Walter himself was discovered by Ellis Thompson-Ellis, a now-retired CNCC science instructor, and her husband outside Rangely in 2014. The pair loved to go fossil hunting with their Great Dane, Walter. They named their discovery after the dog.

Johnson visited the site and quickly realized it was a “once-in-a-lifetime specimen.” The bones stuck straight out of the cliff and many rocks held impressions of dinosaur skin. The team identified Walter as a hadrosaur, a massive plant-eater from the Cretaceous Period.

While Johnson knew Walter could keep a paleontology program busy for years, the idea wasn’t easy to get off the ground. Literally. Even after the school won a permit from the Bureau of Land Management to house the Walter, it had to find a way to lift him out of a steep quarry.

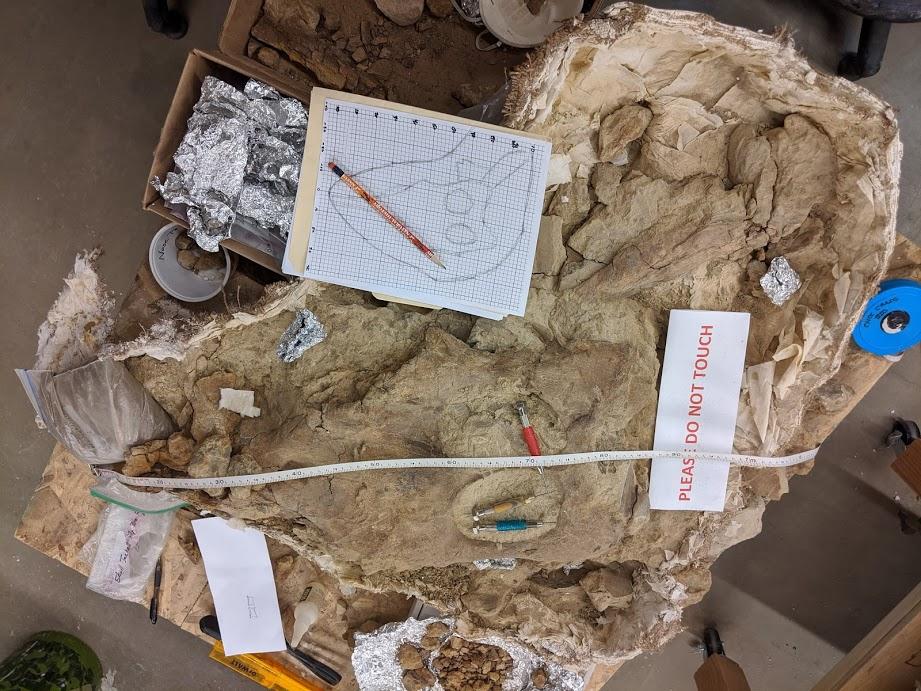

The CNCC team extracted the fossil and split it into a pair of plaster-encased jackets. Each weighed more than 1,000 pounds. To raise the piece to a road, the school enlisted help from the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control, which had a spare helicopter in the area after responding to a nearby wildfire.

Johnson remembers watching the jackets dangle from a 100-foot cable.

“I’m just like, ‘Please be in one piece. Please be in one piece,’” she said. “I’ve never been more nervous.”

Walter made it safely out of the quarry and into the CNCC basement. That’s where 18-year-old student Gabriel Nevolo loves to spend his time, chipping away at the rock and plaster with careful precision.

“It’s like Christmas morning every time,” he said. “Every little piece that you break apart gives you a bigger picture of the puzzle you’re trying to uncover.”

Nevolo grew up in New York and heard about the CNCC program through another student’s Facebook post. Besides working on Walter, Nevolo has tracked down a discovery of his own: a rock he suspected was some sort of dinosaur skull. He affectionately refers to it as his “potato baby.”

“Just because, when we wrapped it in tinfoil to bring it back — it looked like a giant baked potato,” he said.

The program has also attracted students from Texas, Florida and Oklahoma. Johnson is confident the program will continue to grow and attract participants. She would especially love to retrain local coal miners.

“They already have half of the experience nailed with the amount of geology that they’ve done. That is a very easy, quick transition,” she said.

But Sahsa Nelson, director of community education for the school, is careful not to overpromise. She said the coming mine and power plant closures represent an enormous challenge for the region. While she agrees a dinosaur museum could help, she cautioned the community simply doesn’t have the resources at the moment. Even if Craig banded behind the project, it’d take a lot of help.

“It’s a very big task,” she said. “Maybe as big as Walter.”