“I’m sensing that there's this peculiar opinion that somehow this is not going to affect us.”

On Monday, March 23, I was working on a story about hospitals preparing for the coronavirus. An emergency room doctor in a big Colorado health system was telling me they were seeing a surge, a doubling each day, in COVID-19 patients.

But, he said, many Coloradans were still in denial and hadn’t yet considered how COVID-19 might impact them.

“If you think for one second that you're walking around, and you're not going to be touched by this, you're going to be touched by this.”

Just after that call, my phone started to hum. It was messages from buddies of mine I grew up with in Denver. Mike Farley had died.

“He contracted COVID,” one friend texted.

I’d been dealing with COVID-19 every day for weeks, covering the story as CPR News’ health reporter, but I hadn’t known anyone who’d yet gotten sick from it.

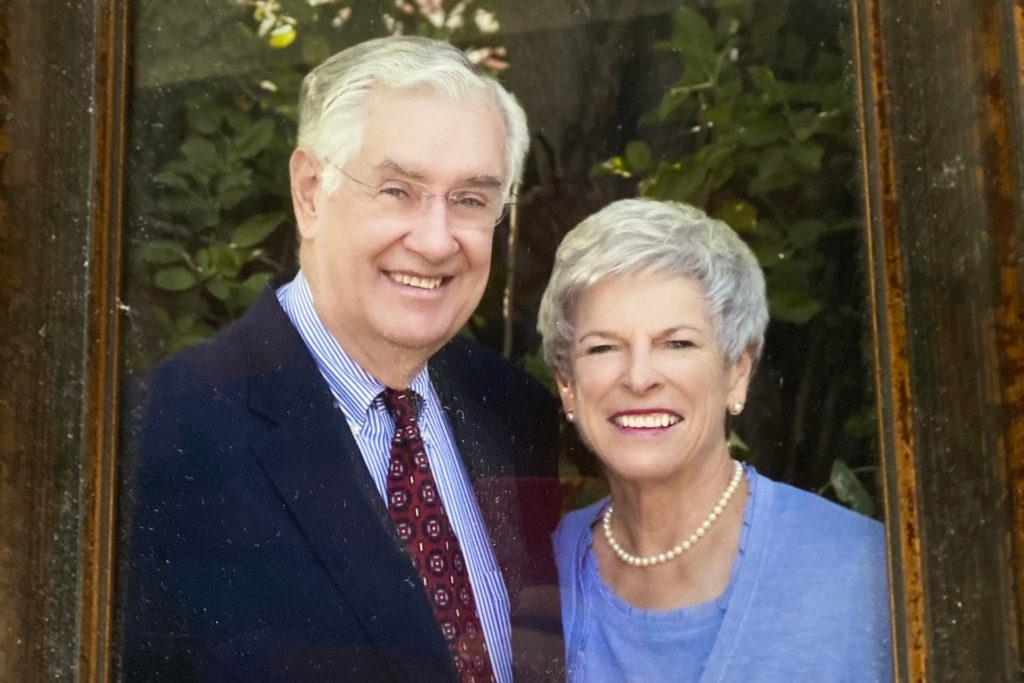

Though I hadn’t seen him in some time, I’d known Mike Farley since I was a kid. Mike’s wife Nancy taught my brother how to play piano. His son John and I grew up swimming and playing soccer together. John and I were high school classmates at Manual High in Denver, part of a tight group that remains close friends today. And I knew Mike’s daughter Maggie, who is a couple of years younger than John, as well.

What I remember best about Mike was his warmth and kindness, always there after a swim meet or soccer game to say “Good job!” or ask about how my folks were doing.

The family called my colleague Ryan Warner to tell him — and the audience of Colorado Matters — their story via cell phone. In the age of the coronavirus, many of us will be touched by stories just like theirs. Nancy and Maggie joined Ryan from Mike and Nancy’s Denver home, John joined from Boulder. All three were self-quarantined due to their contact with Mike.

Maggie lives outside of D.C. and said, “I just couldn't imagine being quarantined there and knowing that she (Nancy) was grieving alone here, and having to do everything that you have to face after death. So I'm just really glad I'm here, even though she won't let me hug her. She's making me stay six feet away.”

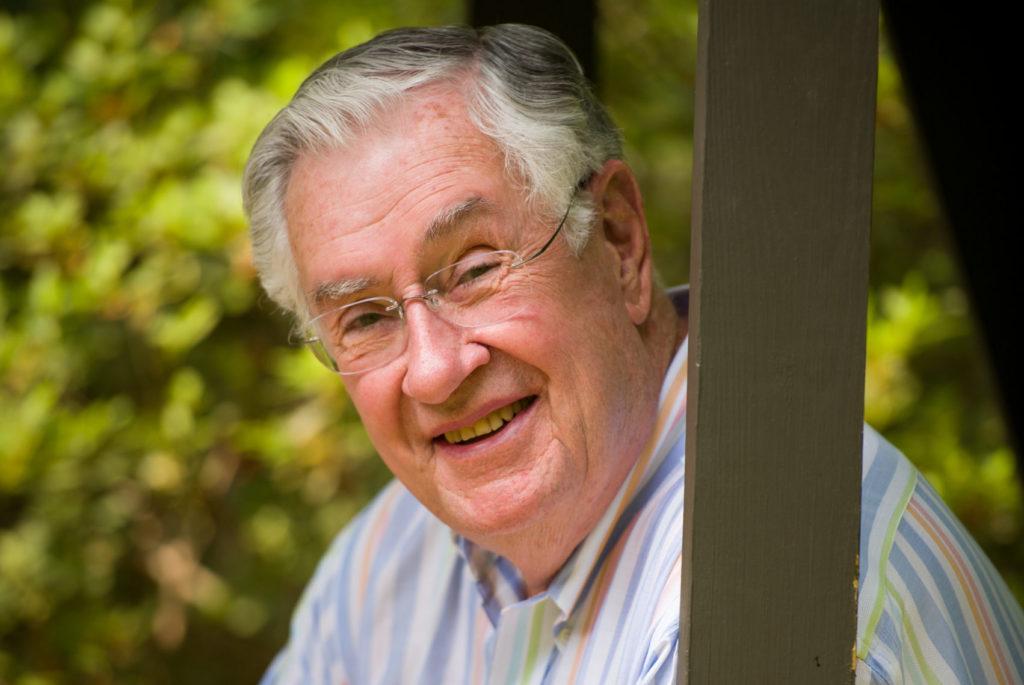

Favorite stories flowed about Mike, a retired lawyer, lover of classical music, avid reader and advocate for those experiencing homelessness.

Nancy said Mike worked on housing for about 30 years through the Archdiocese of Denver.

“That really was his passion,” she said. “He loved to drive by the sites that they had built and see families out in the yards playing.”

John remembered coming down from their neighborhood in Park Hill and visiting his dad at his office downtown as a teen. They’d go to Duffy’s Bar and Grill and walk the 16th Street Mall.

“What happened just amazed me, because Dad couldn't walk but 10, 20 feet at a time without someone saying, ‘Hi, Mike.’ ‘Hi, Mike.’ ‘Hi, Mike.’”

Maggie recalled her dad’s “stubborn sense of justice.” Besides fighting for low-income housing, he also pushed his firm, Holland and Hart, to diversify, and took to the U.S. Supreme Court a case that ultimately mandated court-ordered busing in Denver.

When cleaning out his desk, Maggie found what she called another symbol of his stubborn sense of justice: a parking ticket that he’d been fighting for three years.

“He felt like it was not fair, and so he was not going to pay it,” she said.

Mike Farley’s illness came on fast and out of the blue in early March.

Nancy and Mike were watching a movie at their house with friends when he started to cough violently and couldn’t stop. Everyone in the room looked at each other.

“Well, we were extremely worried. We thought, ‘Oh my goodness, maybe this is the dreaded virus,’” Nancy said.

The friends left immediately. Mike finally calmed down a little bit later, but from then on, his cough just got worse. He developed a slight fever. They called the doctor, who had him come in, and prescribed antibiotics.

Mike came home and just didn't get better.

The next time they called the doctor, about five days later, they were told to please take him to the emergency room.

"Which I did,” Nancy said, “and that's the last I saw of him.”

That snowy day, a Thursday, Nancy took Mike to Swedish Medical Center in Englewood. He was admitted at the front desk, and due to early visitor restrictions imposed to slow the spread of the new coronavirus in the state, she was told she’d have to wait in her car.

“I think people were, minute-by-minute, finding that they had to apply new rules to everything,” Nancy said.

After about an hour, Nancy returned to the front desk. “I said, ‘What is going on?’ Finally, somebody did come back and say, ‘We're admitting Mike to the hospital because he has bilateral pneumonia.’”

It was the illness commonly associated with COVID-19.

They spoke on the phone a little while later. Mike was desperate for some books, including one called ‘The Bishop’s Pawn,’ “probably a mystery,” Nancy said. He only had about 20 pages left in one of the books, and Nancy brought over three to the hospital.

A kind nurse taught Mike how to FaceTime on his cell phone, enabling the whole family to connect. Soon, Mike’s oxygen levels were falling, dangerously low, and he was moved to an intensive care isolation unit and got hooked up to a respirator.

“He explained to me that he didn't think it was good news at all, that it really means that we need to say our goodbyes, just in case. And so we did,” John said. “It was very difficult to see him through FaceTime, struggling to breathe, while he so desperately wanted also to talk and connect and tell me how much he loved me, how much he wants me to look after my mom, and how much he loves my sister and her family. So that was the end of the call.”

Sunday night, they had another five-minute exchange. Mike’s condition was on a roller coaster, very notable in many COVID-19 cases. The day had started out with some promise. His oxygen levels had crept back up, but by day’s end they’d started to drop again.

“He reached out and said that he really didn't think he'd be around tomorrow, and I said, ‘Oh Dad, I look forward to FaceTiming and seeing you tomorrow morning,’” John said.

“And he said, very directly, that he didn't think that was going to happen, but he hoped so. That was the last time we spoke.”

Mike understood the outcome for people at his age, with his situation having “a little bit of an underlying lung condition anyway” was not good, Maggie said.

“He clearly had a sense of the way things were going. He said, ‘This is not the end-of-life situation I hoped for. This is really hard,’” Maggie said. “And he said he felt like his life was complete, but he just wasn't ready to hand it over yet. He did make a very brave choice in the end. He chose not to be put on a ventilator.”

She said it would be very much her dad’s way to decide to open up the use of a ventilator for another patient.

“But I think we regard it as a gift to us, actually. I think he was envisioning a future when he would come home and just be stuck on oxygen and be kind of a burden to the family and not be able to go anywhere,” Maggie said. “He just decided he would rather have a better life rather than a longer life.”

On Monday, five days after entering the hospital, Mike Farley died.

And like many sick patients in the COVID-19 era, he was alone. His last rites were administered remotely.

“It had a surreal quality to it because it was happening over a phone,” said John.

Mike’s son said he was grateful that the family could connect that way.

“I could feel all of us breathing, talking, being on the line together, and that brought great comfort. And I just projected and hoped that the projection of that, that Dad truly felt it and knew it. I think he did. But I found it to be a, yeah, a very surreal experience, to say goodbye that way.”

“When he died, I thought it was a tragedy,” Maggie said. “Even though we got to listen to the last rites over the nurse's phone, I felt so sad for him, because he was essentially dying alone and I know he didn't want to.”

Reflecting on it a week later, Maggie thinks the Farleys were actually lucky. Because within that week the number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. had shot up by five times what they were. At this rate, there could be a million cases by Easter. As the numbers skyrocket, she said, nurses won’t have ventilators to put people on or the time to make phone calls.

“There is not even going to be equipment, maybe, for the doctors and nurses, and they could end up victims themselves,” Maggie said. “So there's going to be a whole lot more people dying alone, and there are going to be a whole lot more doctors and nurses who don't have masks and gloves if we don't fix this. And I think that is absolutely criminal. We saw this coming and we were utterly unprepared.”

The Farleys wanted to share Mike’s story to underscore the serious, mysterious and super-contagious nature of COVID-19.

And the importance of taking all the recommended mitigation measures, of washing hands, staying home, keeping your distance. “If we can save one life we’ve done something great in Dad’s name,” said John.

Still, when a loved one dies from COVID-19, the survivors are left with ‘what if?’

Maggie, who was doing a lot of traveling before she visited her parents and Mike got sick, has lain awake at night wondering if she could have given it to him.

In her goodbye call, she said, “‘Dad, if I gave this to you, please forgive me. I was trying to be so careful.’ And he absolved me. I mean, that was a real gift. And he said, ‘You did not give this to me. It doesn't add up, and I could have gotten it anywhere. At the doctor's office or at the grocery store,’” she said.

“We've all had those dark moments, wondering where he got it and if we brought it to him.”

Research has emerged that shows a high number of those infected with the new coronavirus may be asymptomatic, meaning they may not show symptoms. That makes it hard, if not impossible, to know who spread the virus to whom.

“I think it's a question we can never answer,” she said, noting it’s “so characteristic of my dad that he forgave me and he tried to talk me out of it.”

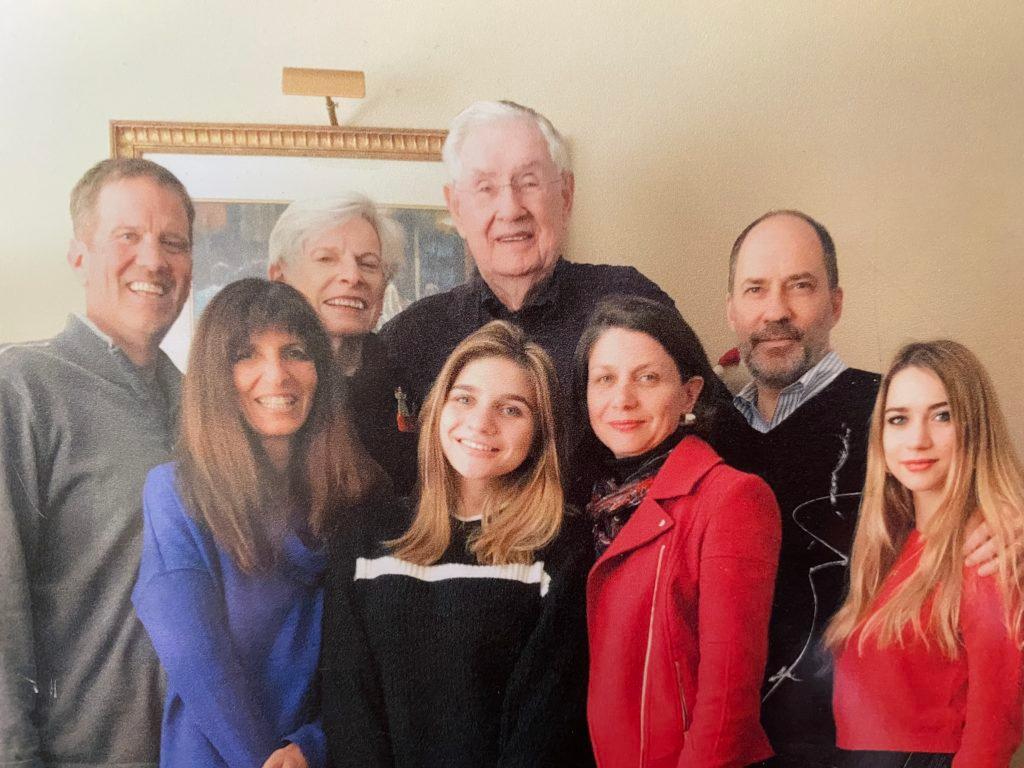

A few days after Mike Farley died, his loved ones joined together via the online video conference site Zoom. They held an Irish wake, which John described as an all-out celebration of one's life, typical to the Irish, with great amounts of laughter, great amounts of crying, and a very funny dark humor.

“It's a blunt humor and it rolls around between family members for hours,” John said.

Farleys from Oregon, Farleys from Montana and Farleys from Wyoming shared recollections, with a lot of fun and a lot of tears. The favorite line came from a cousin, Justin, who said “‘This is the first wake I've been to that didn't require pants.’”

It seemed a fitting farewell for a man who, when asked what he wanted for his birthday or Christmas would always say, “All I want is love and a few kind words.”

“He is getting everything that he wanted in abundance,” Maggie said.