Even before the coronavirus pandemic enveloped Colorado, Amy Delpo had struggled to have the end-of-life planning conversation with her father who has been diagnosed with Parkinson's and Alzheimer’s for the past year. The outbreak has sped up that process.

Her father does have a living will and it’s a topic that’d come up after her mother died, “but we were talking around it and avoiding it at the same time,” she said. “Corona has really forced the issue of what he wants to happen.”

As cases continue to mount, state health officials are urging Coloradans to prepare advanced directives with their loved ones in case a family member falls severely ill with COVID-19 — including what medical interventions a person does or doesn’t want.

Delpo emphasized her father does have a good life. He lives in his own apartment but she comes over to give him care. Before COVID-19 measures, he spent ample time with her, her husband and her children. Social distancing has been particularly difficult for him because his condition causes him to forget the need for social distancing.

“It’s hard for an older person, especially one with memory challenges to remember why I’m not giving him a hug when I walk in the door,” Delpo said. “It’s never theoretical but it’s much more present now... the choices that will have to be made,” she said.

Delpo describes the topic as “being in the air” and it has made him more willing to talk about it.

Tyler Murray, an estate lawyer with Denver-based Murray and McCarthy Law, has seen an uptick of people inquiring about end-of-life planning ever since the start of March. He recommends setting an appointment with an expert so people can make the most informed decisions. It’s also important to tell the people who are directly responsible for decision-making.

“At least tell the ones who will be in charge,” he said. “I don’t necessarily recommend telling your whole family since that can cause some issues if one doesn’t agree with your decisions.”

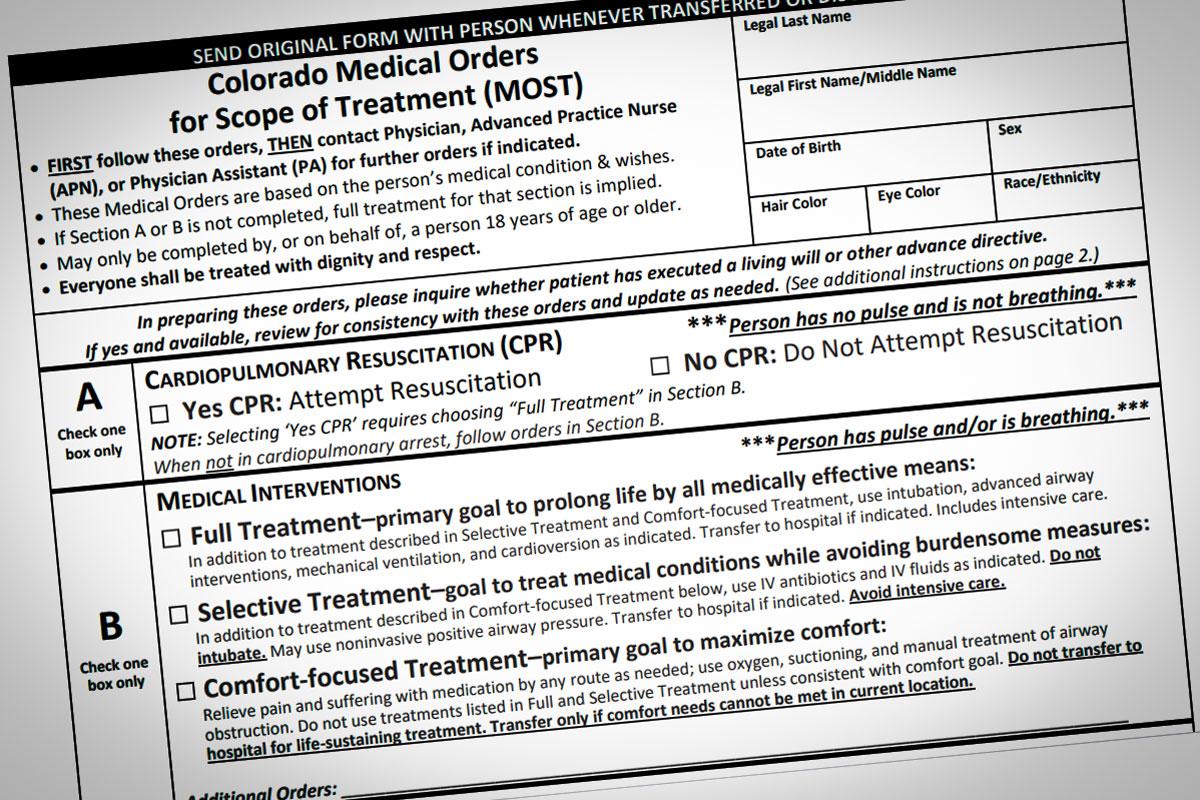

Those people in charge should complete the Medical Durable Power of Attorney form which is a legal Colorado document to choose a medical decision-maker to speak on your behalf if you’re unable to make those decisions because of an illness or an injury. The alternative is the Easy-to-Read Colorado Advance Health Care Directive which allows you to choose a decision-maker and allows you to outline how you would like to be cared for.

Because that is a living will, it will need to be witnessed by two people. Anyone over the age of 18 can determine their decision-maker with this form.

The Colorado Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment form is a set of medical orders for specific medical care like do not resuscitate orders. This needs to be signed by you, the doctor, nurse practitioner or physician assistant. UCHealth also has a list of resources for end-of life planning.

In the experience of Melissa Davis, a licensed clinical social worker with The Denver Hospice, framing the conversation as something that will benefit loved ones can make the conversation easier.

“There’s a burden on their loved ones sometimes leaving them to say ‘I hope that I’m doing what my father or my mother wanted,’” Davis said. “That’s where giving thought to this really can be a gift to your loved ones to prevent people from saying ‘Gosh, I have to live with this decision for the rest of my life and I don’t know if I made the right one.’”

Dr. Hillary Lum, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, said people should make decisions based on their perception of the quality of life.

“The questions about a do not resuscitate order are emotional and important to have accurate information,” Lum said. “Thinking about whether someone wants a do-not-resuscitate or not should be related to what is the likelihood of that procedure being beneficial to a person who restarts their heart and lungs but also return to a life that they value.”

When someone has a serious or terminal illness, she said it’s important to understand that a person’s medical health after getting those CPR procedures is not high.

Across the board, the three experts agree that the most important thing you can do is to have all your wishes in writing.

Keith Brown from Telluride, 61, and his wife just decided to complete their advanced directives.

“We felt like ‘Oh my gosh, we better do it now if we’re ever going to do it,’ was one [part],” he said. “The other was that we understood the need for directives but we never got around to it. The special urgency now is COVID-19.”

Brown described both himself and his wife as relatively healthy but he recognizes that he’s fearful of contracting the novel coronavirus.

“I want to do the right thing for everybody,” he said.