In Colorado, doctors and researchers are desperately looking for ways to treat patients with COVID-19.

Right now, there is no proven effective treatment, and it could be many months before a vaccine — or a treatment to alleviate symptoms — is tested and available for widespread use. Research into some drugs and treatments are farther along than others, and many show signs of promise.

Here’s where things stand.

Vaccines

We’ve eradicated smallpox and made diseases like the measles manageable through the use of vaccines. Those treatments are some of the biggest breakthroughs in public health, but they require time and money.

The World Health Organization announced in February that a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, could be ready in 12-18 months, but some scientists argue that the timeline may be unrealistic. Typically, a vaccine can take 5-15 years to be developed, tested in clinical trials, and manufactured for distribution.

Around the country, several biotech companies have started human clinical trials of a vaccine, and it’s likely that multiple vaccines will be developed.

At Colorado State University, Gregg Dean, professor and head of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, was working on a vaccine to treat a strain of coronavirus that cats contract when he shifted gears to address the strain that’s now causing the pandemic.

“Our experience with viruses in animals is quite valuable. This involves work by veterinarians and nonveterinarians to study these viruses in these nonhuman species,” Dean said. “When we think about the current pandemic, this virus has come out of an animal reservoir and it's jumped into the human population. Our understanding of those animals, the viruses they have and how these sort of emerging pathogens can come about is really critical.”

Dean and his team are working on a vaccine made from the bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus, a probiotic found in yogurt. This bacterium thrives in the mucous membrane — the tissues of the nose, mouth, throat and lungs — which is where the new coronavirus gains entry into the body.

The researchers engineered a form of the bacterium to block the virus from invading cells, exploiting the viruses “Achilles’ heel.” They're still developing the vaccine but hope to begin animal trials in the coming months to determine if it will be a good candidate for humans.

Over in Aurora, Greffex Inc., a Texas-based company, is developing an adenoviral vector-based vaccine. Scientists take an adenovirus, clear it of its disease-causing material and then introduce a part of the virus that causes COVID-19 into the viral shell. When injected into a person, the body will mount a response that results in immunity to the virus without having been exposed to a live or killed virus.

"The benefit is speed to get to the vaccine, cost, because ultimately when you get to production, you want to make a vaccine that's significantly cheaper for the population and safety," said John Price, CEO and president of Greffex Inc. "If you don't use a live virus or a killed virus, you're really not introducing anything that could be harmful to begin with."

Read more about that vaccine here.

Drugs

It’s likely that one of the first treatments we’ll see in widespread use for COVID-19 will be one that uses an already-approved drug, like the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine that President Donald Trump has pushed for.

Drugs that are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration have known side effects and manufacturers know how to produce them, but they aren’t likely to be the cure-all for COVID-19. These drugs are not likely to cure COVID-19, but they may alleviate the symptoms associated with the infection and keep them from becoming more severe.

Dr. Thomas Campbell, at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, is working on a clinical trial of sarilumab, an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. The trial was developed jointly by the pharmaceutical companies Regeneron and Sanofi. Hospitals all over the country will enroll hundreds of patients. In Colorado, Campbell has enrolled about 15 so far.

Sarilumab blocks the activity of a protein in the body that regulates inflammation. Many patients with severe COVID-19 develop hyperactive inflammation in their lungs. By targeting the inflammation mediator, patients may see improvements with this drug.

“The idea is that if you can reduce that inflammation, interfere with that inflammation, then people will get better quicker,” Campbell said. “If they're not on a ventilator, they might not need to go on the ventilator, or if they're already on mechanical ventilation, they might come off of mechanical ventilation sooner than later.”

Antiviral Inhibitors

When someone is exposed to COVID-19, the virus attacks the body’s cells and then starts to replicate itself. That replication process is what allows the virus to spread in the body and make us sick by damaging other cells or disrupting cell function.

Antiviral inhibitors prevent the virus from replicating, stopping or slowing the spread and allowing the body to catch up and recover. Campbell said UCHealth will start clinical trials of remdesivir, developed by the drug company Gilead Biosciences, in the coming weeks. One trial will focus on patients who have mild to moderate symptoms, and the second trial will focus on more severe patients.

Jed Lampe, assistant professor in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the Anschutz Medical Campus, is working on an antiviral inhibitor used to treat HIV. He and his team are modifying the drugs ritonavir and lopinavir. Lampe said there is some clinical evidence that they may be useful against COVID-19.

“What's nice about taking this approach where we're starting out using these old inhibitors that were very effective at treating the HIV virus to treat this virus is that we know that they are already safe and effective at least against that virus,” Lampe said.

But for the inhibitors to be effective against the novel coronavirus, Lampe and his team are having to make changes to the shape of the inhibitor so that it better fits this virus. One problem with antiviral inhibitors is that as the virus mutates, the inhibitor becomes less effective. In treating HIV, doctors use a cocktail of drugs for this reason.

“We hope that this iterative process … that that'll lead to a library of compounds that we can use to treat the viruses that haven't even been identified yet, or mutant viruses in the future,” he said.

Listen to Colorado Matters’ interview with Lampe.

Convalescent Plasma

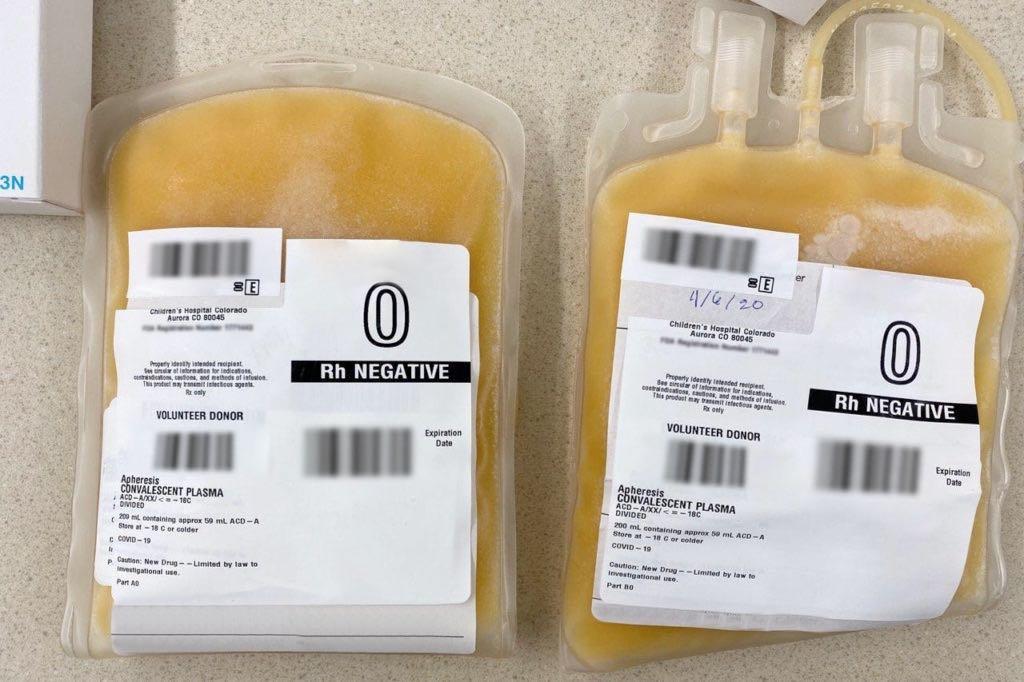

When you get sick with a cold or the flu, or even when you have an allergic reaction, your body reacts and creates antibodies. Those antibodies are part of your immune response when you’re exposed to that virus or allergen in the future. For COVID-19 patients, receiving the plasma from someone who has recovered from the virus can help their body to fight off the disease.

COVID-19 convalescent plasma has been used by doctors at UCHealth to treat severe cases, and it’s showing promise.

“There is hope in this treatment,” said Dr. Kyle Annen, medical director of the blood collection center at Children’s Hospital of Colorado. “However, it's not a certainty. We don't know for sure that it is the best option or the only option. It may be a great option with other medications. There may be another medication that comes along that is identified to work better. But it's great that we have this one additional thing in our arsenal to try to fight COVID-19.”

There’s anecdotal evidence that plasma was used to treat sick people during the 1918 Spanish Flu, and it was used successfully to treat H1N1 flu in 2009-2010, but in other cases, it’s not been effective. The Food and Drug Administration released its guidelines for giving convalescent plasma to COVID-19 patients, and has encouraged researchers to begin clinical trials to investigate its efficacy.