Four weeks into a stay-home order, Coloradans have begun to wonder when they might get to go out again — and what the world will look like when they do.

While public health experts say there is much that is still unknown, here’s one possible future, what they say is a best-case scenario: The state has widespread testing, ideally both testing for COVID-19 via a swab and blood testing. An army of public health workers or temporary volunteers identify the sick, of which there could be many more, experts warn, and track down everyone they’ve come in contact with, a process called contact tracing. Those people could then be isolated. Or maybe the state deploys an app that tracks who has been near whom or a form to fill out.

Some businesses, and maybe schools, are open again, but only if people are kept 6 feet apart and everything is regularly disinfected. Until the virus is totally controlled, high-risk people are isolated or monitored and the state is focused on stable supply chains.

And eventually, there are proven treatments and a vaccine. The virus is brought under control.

CPR News spoke with a number of people with a deep understanding of the key factors that would go into decisions about Phase 2 of dealing with the pandemic after the state exits what Gov. Jared Polis has referred to as the “urgent” stage. They paint a picture of uncertainty, tradeoffs and the need for massive scaling of a health system that has so far struggled to keep up with the pandemic.

Colorado Likely Needs Far More Testing To Get Control Of Coronavirus

For weeks, the pandemic response effort in Colorado and the U.S. has hinged in part on testing, which has lagged badly behind demand. That may be about to change. “We are on a precipice to ramp up” both more standard tests and more rapid tests, said Dr. Michael Wilson, who directs lab services at Denver Health Medical Center, one of the state’s key test labs.

Wilson said he was on call in the second week of April with White House coronavirus response coordinator Dr. Deborah Birx and other lab directors around the country. He said the estimate was “we need to essentially double what we’re doing.” The number of tests conducted daily in the state has fluctuated between around 1,000 reported on April 13 to around 2,700 reported on April 11, although not all negative results are included. The state health department has not shared specific numbers on exactly how many tests it is aiming for.

Two things have been in short supply, the collection kits and the medium to transport them, which continues to be an issue. Several “manufacturers are scaling up as fast as they can.”

Those manufacturers make tests with names like BioFire and ID Now and they’re capable of turning around tests much faster than before.

“We seem to be right on the edge of more rapid tests,” Wilson said.

The COVID-19 tests he and his lab staff have processed take perhaps eight hours to yield a result. The new tests will bring the turnaround time down to an hour or less, which will make it easier to diagnose patients sooner, helping to inform treatment or hospitalization decisions for doctors.

Wilson’s lab currently does between 150 and 300 tests a day, but the number could be elevated to 500 daily. Usually, two workers a shift can run six machines that process tests in different machines made by different manufacturers.

“If we were running full out, we could do up to 500,” he said.

Those are traditional COVID-19 tests, where they test for the presence of the virus and its genetic material. But tests that look for the antibodies the body produces to fight the virus, a sign someone has been exposed, may also help trace the virus in later stages of an outbreak.

These tests, called serological tests, are on the way too, although their reliability is questioned by some public health experts.

“We are within 2 to 4 weeks” of having good serological tests that can be deployed, Wilson said. “We're cautiously optimistic.”

Dr. Michelle Barron, medical director of infection prevention at the University of Colorado Hospital, said, so far, “The swab test is really quite good in terms of being able to detect active virus.” If you test positive and have symptoms, she said, “you can be pretty certain you have the disease.”

She was more skeptical about the antibody tests.

“The problem with some of the commercially available antibody tests right now is that they cross-react with the common cold coronaviruses,” she said. “So they can't tell the difference. And so you're kind of in this like, ‘Well, does that mean I had a cold?’”

If they can’t reliably detect the virus, people who have not yet actually been exposed may not take the necessary precautions.

A cautionary tale on testing could be seen in recent days in New Jersey. As The New York Times reported, a backlog of cases there was getting worse. People looking to get tested faced lines a mile long at a drive-up test center. There were holdups, from a lack of kits and swabs and chemicals to tell if a sample was positive for the virus. Samples got shipped across the country because local labs were swamped.

“It's a model of how you don't want to do things,” said Dr. Jonathan Samet, the dean of the Colorado School of Public Health. “We need a well-worked-out system.”

The leader of a key doctor’s group said testing and treatment will need to be much better before restrictions can be reasonably lifted. “I think before we can really move to a next phase, we're going to have to greatly expand testing capability,” said Dr. David Markenson, president of the Colorado Medical Society. He described the tests as the “Achilles heel” of the pandemic response, and it would require both surveillance testing and more testing of the sick “to learn which restrictions and in which communities we can start pulling back.”

He also worried supplies of protective equipment, needed by frontline health workers and those conducting tests alike, would continue to plague the response effort. Despite efforts from federal, state and local leaders to secure more, “we still do not have enough PPE.”

Julie Lonborg, of the Colorado Hospital Association, said a steady stream of supplies would be essential to a safe reopening. “Making sure that those are reliable channels and reliable sources is critical to us entering this next phase and going through that in a responsible way,” she said. While the state has made some progress, doctors and public health experts say testing supplies and protective equipment still aren’t keeping up with demand.

The clearest indication of that is that the state’s chief medical officer has activated emergency medical standards, called crisis standards of care, for protective equipment.

The guidelines, approved by Gov. Polis, inform urgent medical decisions, as COVID-19 could overwhelm hospitals.

"I'd say over the 31 years of my career, it never occurred to me that I might be in a place where we'd have a shortage of personal protective equipment," said Colorado Chief Medical Officer Eric France. The guidelines give providers advice for reusing equipment like masks without fear of legal liability.

Similar standards for hospital resources, like ICU beds and ventilators, haven't yet been activated.

What A Safe Reopening Looks Like

If Colorado lifts its social distancing measures, public health leaders agree that testing alone won’t stop a resurgence of the virus.

The strategy would need to be paired with expansive contact tracing. The process is like a game of epidemiological whack-a-mole: If one person tests positive, health officials get in touch with all of his or her contacts. Each of those people would be quarantined and monitored as well. If they test positive, the process would repeat until the transmissions stop.

While the process isn’t new for state and local public health departments, the scale would be unprecedented.

Some have likened the societal transformations on the horizon broadly to launching a Marshall Plan, the massive U.S. push to help rebuild Europe after World War II.

“The person power is potentially available and we've got lots of models for scaling up contract tracing, both in the U.S. and around the world,” said Glen Mays, an expert in emergency preparedness at the Colorado School of Public Health.

In a press call Tuesday, state epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is recruiting professional and student epidemiologists to expand Colorado’s contact-tracing capacity. She added local health departments are doing the same.

Some countries have turned to surveillance technology to ease the burden. In China, where the outbreak began, an increasing number of people must show a QR code on their phone to enter a wide range of public spaces. The software assigns people a color — red, yellow or green — to determine whether their COVID-19 risk and whether they should enter quarantine. In South Korea, cameras and credit card transactions help monitor the spread of the disease. If someone tests positive in Hong Kong, health officials won’t release their name but will provide age, gender, location and even a place of work. The strategy is meant to warn others of a possible infection.

Such strategies could face resistance in places like Colorado, where people put a higher value on privacy.

Herlihy said the state currently doesn’t plan to use cell phone tracking data to assist its contact tracing efforts. It is, however, considering methods to collect data from individuals electronically instead of through more traditional interviews, which require far more time and manpower.

“There’s a balance in using technology to support this work,” Herlihy said. “Obviously, protecting individual privacy is a priority.”

Colorado Is A Long Way Off From Tracking

If the statewide stay-at-home order is lifted, much of the work of tracking those infected with the new coronavirus and those they may have come in contact with will likely fall to local public health departments.

CPR spoke with a half-dozen public health departments across the state about the current status of their contact tracing, testing and plans to ramp both up. Many of those contacted cited limited supplies and personnel, as well as budget constraints worsened by the COVID-19 crisis.

Tri-County Health serves Adams, Arapahoe and Douglas counties. Dr. Bernadette Albanese, a medical epidemiologist with Tri-County, said contact tracing will be an important part of keeping the novel coronavirus contained as stay-at-home orders are lifted.

“They're the next pool of people to get sick,” Albanese said. “So it absolutely will be [important]. It has to be.”

Her department continues to see “a lot” of COVID-19 cases that need investigation. For contact tracing to be doable, she said that case volume needs to be manageable.

Tri-County already conducts contact tracing, but Albanese said it’s limited because of the large caseload. They’ve focused on educating household members who live with a COVID-19 patient, since “they’re really kind of ground zero, so to speak, in terms of the amount of exposure.”

Albanese said they’ve had “very little” capacity to do contact tracing beyond that.

“That’s hopefully what we can get back to in the next phase,” she said. But they don’t have what they need.

“Yet. That’s what we’re working on,” she said.

Other Colorado public health departments conducting some form of contact tracing include Eagle, El Paso, Weld and San Miguel counties.

Health officials in Eagle, an early hotspot in the COVID-19 outbreak, wrote in an email that they do feel like they have what they need for adequate contact tracing, and have already ramped up their capacity to do so. They “see the need for maintaining a higher level of epidemiology capacity throughout the summer and possibly into the fall.”

San Miguel was the first county to embark on testing for all residents, using serological tests.

“Our county continues to struggle with the national shortages, including the bottleneck of testing,” said an email from Grace Franklin, public health director for San Miguel. “We continue to monitor our supplies, and don’t have full confidence to easily be able to replenish our supplies.”

She wrote that contact tracing and quarantine is a less-effective option when there are “significant delays due to testing bottlenecks.”

Health officials in El Paso County, which has 668 cases and 43 deaths to date, shared in an email that the county has more than tripled the size of its communicable disease team to almost 30. The department is also working with medical examiner staff, and University of Colorado Colorado Springs nursing students and staff to assist with investigations and contact tracing.

Weld County, second only to Denver in the number of deaths at 57, has pulled staff from other divisions. Without enough test kits “needed to ensure that we are identifying most or all of the cases,” the county is planning to collect information electronically through a survey, to help with tracking the number of people who are experiencing symptoms, “so that [the county] can plan mitigation efforts effectively.”

Others aren’t doing any contact tracing, including Denver, where 1,468 people have been diagnosed with the disease as of Wednesday’s report and 61 people have died of the disease.

In an email, officials wrote that Denver is assessing how best to reinstate contact tracing since it became less effective as community spread of the disease took hold. They wrote that once there are fewer cases, “and we can better identify where individuals may have contracted COVID-19, and with whom they had been in contact with after, it may become effective to return to contact tracing and use of quarantine to ensure we do not see another rise in case counts.”

The email noted that, “Because of the huge hit COVID-19 has taken on our economy, we don’t plan on hiring new employees [to conduct contact tracing], but hope to pull in volunteers, like graduate students and retirees to help.” In emails obtained by CPR, city officials revealed that they are beginning the development of a recovery plan.

Albanese, with Tri-County, said there’s planning at the state and local level, “and coordination between the two,” for what to do when people get sick in this next phase of COVID-19 response. That includes testing, to “rapidly find out if they’re infected,” along with “trying to come up with innovative ways” to identify and communicate with people who’ve come into contact with the novel coronavirus.

“It’s a huge process underway, a huge effort,” Albanese said.

Once restrictions are lifted, she’s nervous people will return to normal social behavior too soon. The state expects another bump in cases and hopes that new technology will help make contact tracing more timely and less manual. “We want the decision to ease [stay-at-home] restrictions to be made carefully,” she said. “We want more availability for lab testing in the Metro area and around the state. That needs to be in place.”

Local public health departments need more resources to be able to respond to cases quickly, like “strike teams,” Albanese said. “To be able to say, ‘We have a new case, let’s draw an investigation around that.”

Technology Can Assist Contact Tracing, But At What Cost?

If Colorado has a role model for the next phase of its coronavirus response, it’s likely Taiwan.

Polis has repeatedly praised the island nation’s response, which stopped the spread of the virus without the autocratic surveillance and lockdown measures now in place in China. Businesses remain opened. Kids are in classrooms. The country’s response has been so effective, it has a surplus of protective medical equipment like facemasks, some of which it recently donated to Colorado, according to a tweet from Polis.

Stanford Health Policy researcher Jason Wang wrote an article for the Journal of the American Medical Association that examined the country’s success. While early interventions prevented anything like the outbreaks now crippling the U.S., he said Taiwan contains a critical lesson for states like Colorado: You can’t completely protect both public health and privacy.

“It’s a trade-off,” Wang said. “You want to do the minimally invasive procedure to protect public health.”

For example, Wang pointed to data sharing across huge pieces of Taiwan's government. In the early stages of the outbreak, the country integrated travel history information into its national health care system. The move allowed doctors to know if a patient had been to a virus hotspot and needed special care or testing.

Wang added Taiwan’s contact tracing program can be an example for other democracies. When the government declared an emergency, it assumed powers to track cell phone data for public health reasons and enforce quarantines. He stressed those additional controls are set to expire next year.

With its new authority, the country has built a system of carrots and sticks to ensure citizens obey 14-day quarantine orders. Government workers provide food and symptoms checks three times a day. Anyone forced to stay home receives payments from the government, which can turn into a fine if that person hops on a bus or visits a grocery store. While cell location tracking assists those efforts, Wang said the government is transparent about what’s happening and why it’s necessary.

“If you do contact tracing, you have to explain to people why you’re using the information, how you’re going to be using it, exactly where you got it from and who’s going to have access,” he said.

As Colorado reopens, Wang thinks the state shouldn’t choose between traditional contact tracing interviews and cell phone tracking. Instead, he said, “do both.”

He suggests epidemiologists should work in concert with new surveillance programs, like the recently proposed plan from Apple and Google. The project would use Bluetooth to record when two people, or at least their phones, come into close contact. Public health officials could then tap into a database to help figure out who needs to be tested or placed under self-quarantine.

What Comes After The Leveling Off

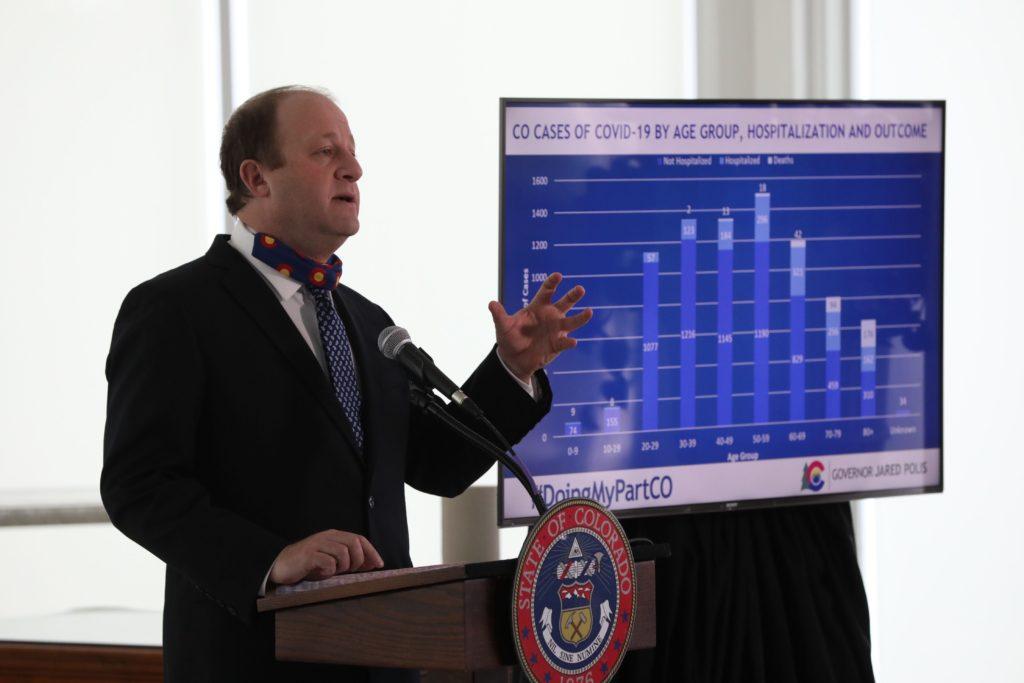

Colorado hit a significant milestone in its coronavirus odyssey on April 15: a leveling off of hospitalized COVID patients.

“As of yesterday [April 15], there were 1,215 Coloradans hospitalized with COVID-19 or with COVID-19 symptoms,” the Colorado Hospital Association said in a statement. “That number had grown steadily since mid-March when hospitals began reporting this data to the state, but it has leveled off in the past week.”

That’s the firmest indication yet that the state has avoided a crisis like the one that has overwhelmed New York and Italy. Hospitals report quieter-than-usual ERs, as the normal car accidents and crime drop with more folks staying home.

Polis has also said strict social distancing has slowed the spread of the virus to the point that the state can build additional capacity for the spike in cases that would follow more interaction, from the Colorado Convention Center in Denver to the St. Mary-Corwin Medical Center and Western Slope Memory Care in Grand Junction.

These are signals the state could be on its way to a gradual reopening. The statewide stay-at-home order is set to expire on April 26, which would put the state into a new phase of pandemic response.

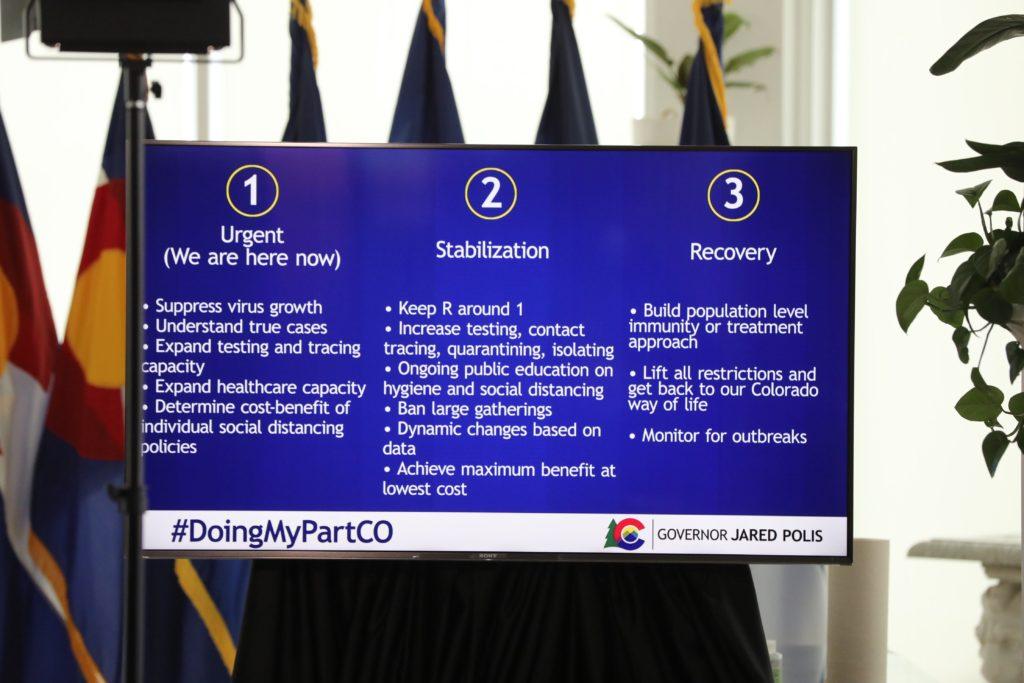

At a press conference Wednesday, Polis laid out his vision for Colorado’s path through the pandemic. He said state officials are planning for a staged recovery: Currently, he said the state is in the “urgent” phase. Once it exits that, it will pass through stabilization and then recovery.

Stabilization would require getting the number of new cases below the point where the virus is spreading widely, increasing testing, tracing, quarantining and isolation, more public education on hygiene and social distancing and a ban on large gatherings.

To “get back our Colorado way of life” — and lift all restrictions — in the recovery phase would require building a “population-level immunity or treatment approach and monitoring for outbreaks,” Polis said.

Other states are preparing plans to ease up somewhat on stay-at-home orders. California, Oregon and Washington have announced a pact to move “toward reopening based on health outcomes.” In a press release, the governors of those states called it a “shared vision for reopening their economies and controlling COVID-19 into the future.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said he and his advisors will look at six areas to figure out how and when to start reopening the economy. Those include expanded testing, protecting high-risks populations, making sure hospitals have enough beds and supplies to adequately care for patients, progress in developing treatments, an ability for businesses and schools to allow for social distancing and an ability to re-deploy stay-at-home orders.

“The most important is our ability to expand our testing,” of those who show symptoms, Newsom said. He also said public health officials would need to identify those in contact with people who test positive for COVID, to figure out how far the virus has spread.

In Colorado, Polis has faced pressure by some Republicans to deliver answers about when restrictions will end and share more about the data he’ll use to guide the state’s response to COVID-19.

In his frequent news conferences, the governor has mostly offered general principles, rather than specific thresholds that would trigger changes.

“We'll be guided by the data,” he told reporters April 13. “Colorado is in the forefront of working on a scale of testing as part of that return to the normal, the different kinds of testing and the different kinds of support that can be provided is very important.”

“We're looking at the data every day to get the economy open as soon as possible, in a way that won't overwhelm our healthcare system and capacity,” he said. “We want to make sure that we're at a point with the capacity on the healthcare side that while the virus will still be with us and people will still have to take steps to engage in social distancing, that we're able to earn a living as quickly as possible. I remain confident that we can do that a few days ahead of time.”

But he has also said the state will require testing “at a much greater scale,” as well as temperature checks as a part of a “return to more normalcy.”

The U.S. government’s top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, made clear, at least at the national level, the country isn’t ready to reopen the economy.

He told the Associated Press a May 1 goal was “a bit overly optimistic” for many parts of the U.S. and backing off more stringent social-distancing rules would need to happen on a “rolling basis.” Fauci predicted a loosening will inevitably lead to a renewed upswing in cases. "I'll guarantee you, once you start pulling back there will be infections. It's how you deal with the infections that's to going count," Fauci told the AP.

The big obstacle: not enough key testing and tracing procedures.