Tori Redden’s 14-month-old son was scheduled to have surgery on his skull last week. It’s been postponed indefinitely.

In March, Gov. Jared Polis issued an executive stay-at-home order. Part of that order required the postponement or cancellation of all non-essential medical services and elective surgeries and procedures until social distancing ends. It was part of the effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19, keep non-emergency surgeries and treatments out of hospitals and preserve personal protective equipment.

Now, as the state inches toward a gradual re-opening, Coloradans are all looking forward to haircuts, manicures, gym workouts and maybe a good, stiff drink on an open restaurant patio.

But no group is as anxious to get things back to some semblance of normal as folks like Redden, and anyone else who awaits surgeries or therapies that they believe are needed, but don’t currently qualify as urgent.

Redden’s son was born with craniosynostosis, a birth defect in which the bones in a baby's skull join together too early. He’s had two major corrective surgeries to break the bones apart in his skull to allow his brain to grow and develop.

The surgery that’s been postponed is the last in the series and it has the highest chance of success if done before 15-months of age, Redden said. Her son will be 15-months-old on April 30. It’s a mostly cosmetic surgery to correct a “divot” in her son's forehead, but she’s upset the surgery has been postponed and worried about his future.

“It could potentially have a big impact on how he grows up and sees himself and how other people treat him for the rest of his life,” Redden said. “I understand there are cases way more severe and more pressing than his, but as a mother, it's hard to hear that my son's not a priority, so to speak.”

The American College of Surgeons issued guidance on March 24 for cancer, cardiac and pediatric surgeries. In hospitals with heavy COVID-19 caseloads, it urged that all surgical procedures be avoided unless the patient is likely to die in the coming hours or days.

Elective and nonessential doesn’t just mean face lifts or knee replacements. Elective surgeries are any scheduled surgery, said Dr. Jeff Cross, chair of the Department of Surgery at St. Anthony's Hospital. The category also includes transplants and cancer surgeries.

“There are literally thousands of operations and there's decisions for each one,” Cross said. “In this pandemic, the question that I ask the surgeons is, 'Is this something that can wait a month?' And if they say, 'No, it really needs to go now or this week or next week,' that would be one that we allow to be put forth onto the schedule.”

Redden worries that her son’s surgery will be pushed out even farther once social distancing ends because of a backlog caused by all the surgeries that have been moved.

Cross said hospitals are aware of the growing backlog, and will do what it takes to treat as many patients as possible.

“I mean, if we need to be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, we will do that to help achieve the ability to treat all these people when it gets to that point with this whole thing,” Cross said. “It is building up. Problems with health, problems with the body, do not stop because of the pandemic.”

In addition to elective surgeries, all non-essential medical care has been postponed. Outpatient clinics, dentist’s offices and physical therapy offices are just a few of the places that are closed or only seeing patients for emergencies.

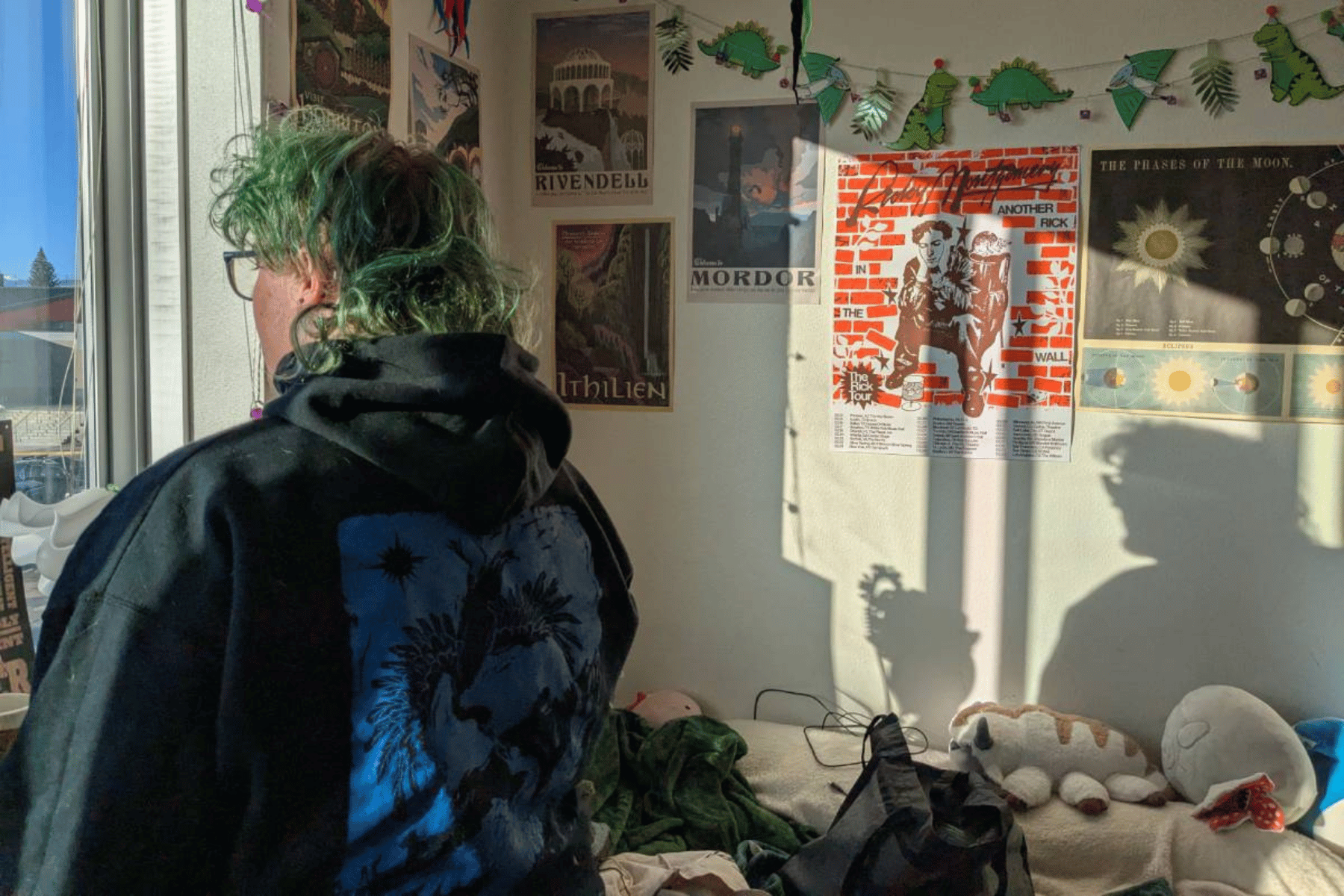

When 29-year-old Andi Rudman wakes up in the morning she has to take pain medicine before she can move.

She has a congenital disorder called Klippel Feil Syndrome. Sometimes, the pain is so bad she passes out.

“I don't sleep well. It's a pretty significant amount of chronic pain," she said. “I'm on opioids to help deal with it and it's never completely managed.”

She was born with fused vertebrae in her neck. Her muscles don’t attach to her bones correctly, and do a lot of the work for the bones. She also has a heart condition associated with the syndrome. The syndrome is rare — Rudman said she’s written most of the Wikipedia page about it.

Once the pain meds kick in, she makes her way out of bed. Her dad makes her food, helps her if she needs a shower and does her laundry. In a normal week, pre-COVID-19, she would visit one of her many doctors almost every day. She sees multiple physical therapists, a heart specialist, and a doctor at an outpatient surgery center who gives her steroid and botox injections.

“Chronic pain is one of the main issues that I deal with, and the way I deal with it is basically by doing lots of physical therapy, some medications, injections and all that kind of stuff,” Rudman said. “Without those, my pain has increased, both my neurologic pain, my muscle spasms and my arthritic pain."

Rudman understands the importance of postponing and canceling procedures to protect people and slow the virus's spread, but she also recognizes that many of the people hit the hardest by the cancellations are sick and in pain.

“I am willing to make this sacrifice to save lives, but I worry that it sets a precedent where this will happen every time there is any kind of global disease outbreak,” she said. “And for me and other patients, I'm sure it will cut years off of our lives and make us have significant issues during quarantines."

On April 17, the ACS issued guidance on resuming nonessential and elective medicine, but when and how Colorado will be able to safely reopen is not yet clear.

So Rudman and Redden, and thousands like them, wait and watch.