At his Wednesday news conference, reporters pressed Gov. Jared Polis on Colorado’s plans for providing mass testing for COVID-19. He responded with a pointed rebuke.

“You're still obsessed with testing,” he said.

If the press is trying to understand his safer-at-home plan, which goes into place when his stay-at-home order expires on April 26, he said they should ask about other strategies to combat the virus.

“I wish everybody was asking about the other three things: the need to wear masks, the social distancing and protecting our most vulnerable,” he said.

The comment marks a stark shift for the governor, who previously cited widespread testing and containment as the key to Taiwan’s and South Korea’s successful efforts to control the novel coronavirus. The emphasis on other strategies shows how his thinking has changed about the next stages of Colorado’s response.

While the state has increased its testing capacity, it still lacks enough tests and public health infrastructure to stop a resurgence if Colorado’s economy reopens all at once.

The governor’s strategy instead focuses on carefully, gradually dialing back Colorado’s current levels of social distancing. Scientists working with the state think it could work while allowing an increase in economic activity, but it also comes with incredible risk.

If the public can’t follow the new, more complicated guidelines, the state could face a second wave of cases that could overwhelm an already stressed health care system.

Public health officials are cautious about lifting rules without more testing.

May Chu, a clinical professor at the Colorado School of Public Health who has advised the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, worries about the potential for a future spike if the state proceeds without ramped-up testing. Without adequate tests, she doesn’t understand how Colorado will be able to break the chain of transmission.

“You don’t know how to put out the fire if you can’t see the light,” she said.

Chu clarified her reaction is a personal opinion and she hasn’t been asked to review the data behind Colorado’s decision, which has been analyzed by Jon Samet, her dean at the School of Public Health. Nevertheless, she fears the plan could overtax health care workers even if hospitals in Colorado have the beds to treat new cases.

Twenty hospitals across the state are predicting protective equipment shortages in the next week. Far fewer predict staffing or bed shortages.

“I’ve seen the doctors and nurses who’ve been stretched beyond imagination. I cannot imagine inflicting things on them if things get out of hand again. It’s just really hurtful,” Chu said.

Dr. Ken Lyn-Kew, a critical care pulmonologist at National Jewish Health in Denver, had been impressed by Polis’ leadership during the pandemic. The more recent announcement has given him pause. He too worries about whether health care workers could handle a new surge in cases.

“I would love to see extra testing,” he said. “It might not work without testing, but the only way to find out is to try.”

To support his decision to move ahead, Polis cited models from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus which show aggressive testing and containment would only allow for slightly lower levels of social distancing. He said that’s because the disease is already too widely spread in Colorado. When a virus first arrives in a population, aggressive testing and isolation can help avoid an outbreak. The state is far past that point.

“At no point did we say we are going to eradicate the virus from Colorado,” he said in his news conference. “If that was the goal, I could guarantee failure. The goal is that as Colorado goes through this difficult period, we have a sustainable way to live and don’t exceed the medical capacity of the state.”

The latest report from the state modeling team tested a number of scenarios that could follow the stay-at-home order. Some of those scenarios included aggressive case detection and containment, but not all.

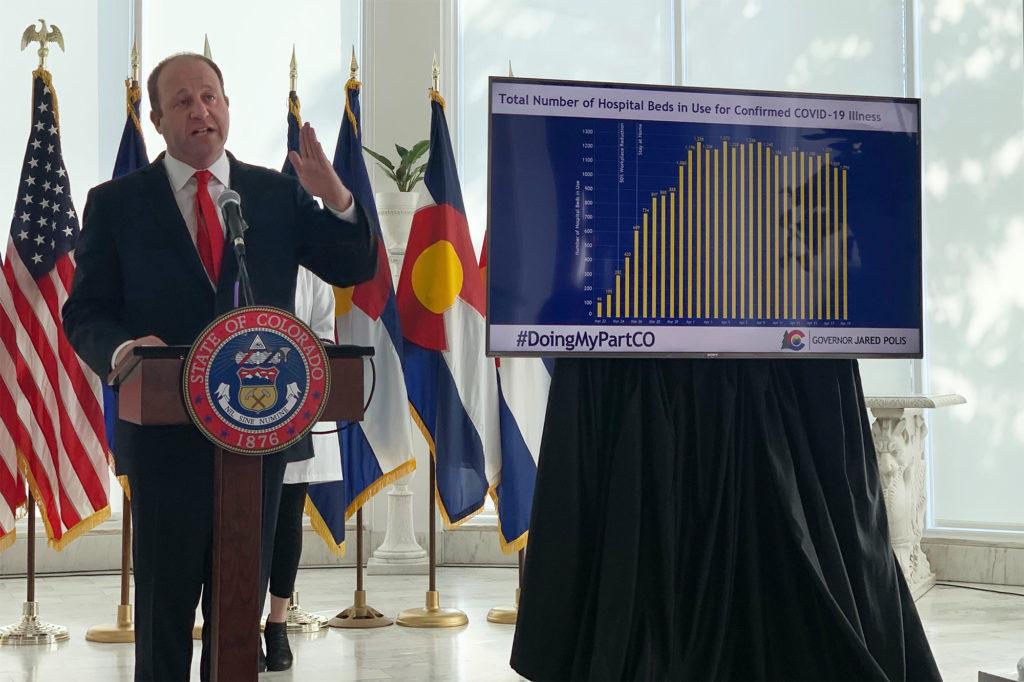

Kathryn Colborn, one of the researchers on the modeling team, said the work suggests social distancing remains the most powerful tool to stop the spread of the disease. The model estimates the degree of social distancing as a percentage. Based on the most recent estimates, the state achieved a 75 percent reduction in overall contacts, which has managed to stop a surge in cases that could have overwhelmed the health care system.

Their latest simulations show the next stage heavily relies on Coloradans continuing to keep their distance. If the state shifts down to 65 percent social distancing, Colborn said Colorado could avoid overwhelming the state’s hospital capacity even without improved case detection and isolation.

“Yes, we can maintain a level of suppression that I think is manageable for the health care system under some of the strategies that don't rely on a huge increase in testing,” she said.

But she warns any model comes with plenty of uncertainty.

Jon Samet, the dean of the Colorado School of Public Health and head of the modeling project, said his team predicts the best-case scenario would be to use a wide range of strategies at the same time. Those include higher levels of social distancing for anyone over 60 years old, mask-wearing and aggressive case detection and containments.

The governor plans to pursue all of the above with his “safer-at-home” strategy.

While Polis said testing remains a crucial piece of the plan, it’s been slow to ramp up.

A spokesperson with the state health department, Gabi Johnston, said between its lab, private labs and hospitals, “we have the capacity to analyze 10,000 samples a day. Of course, that's depending on having the supplies.”

To date, those labs haven’t yet had close to enough supplies to test at that level. The most tests the state has been able to run on a single day was 2,690 on April 11, according to data released by the health department. In recent days the levels have been lower than that. For example, on April 21, about 2,200 tests were completed and reported.

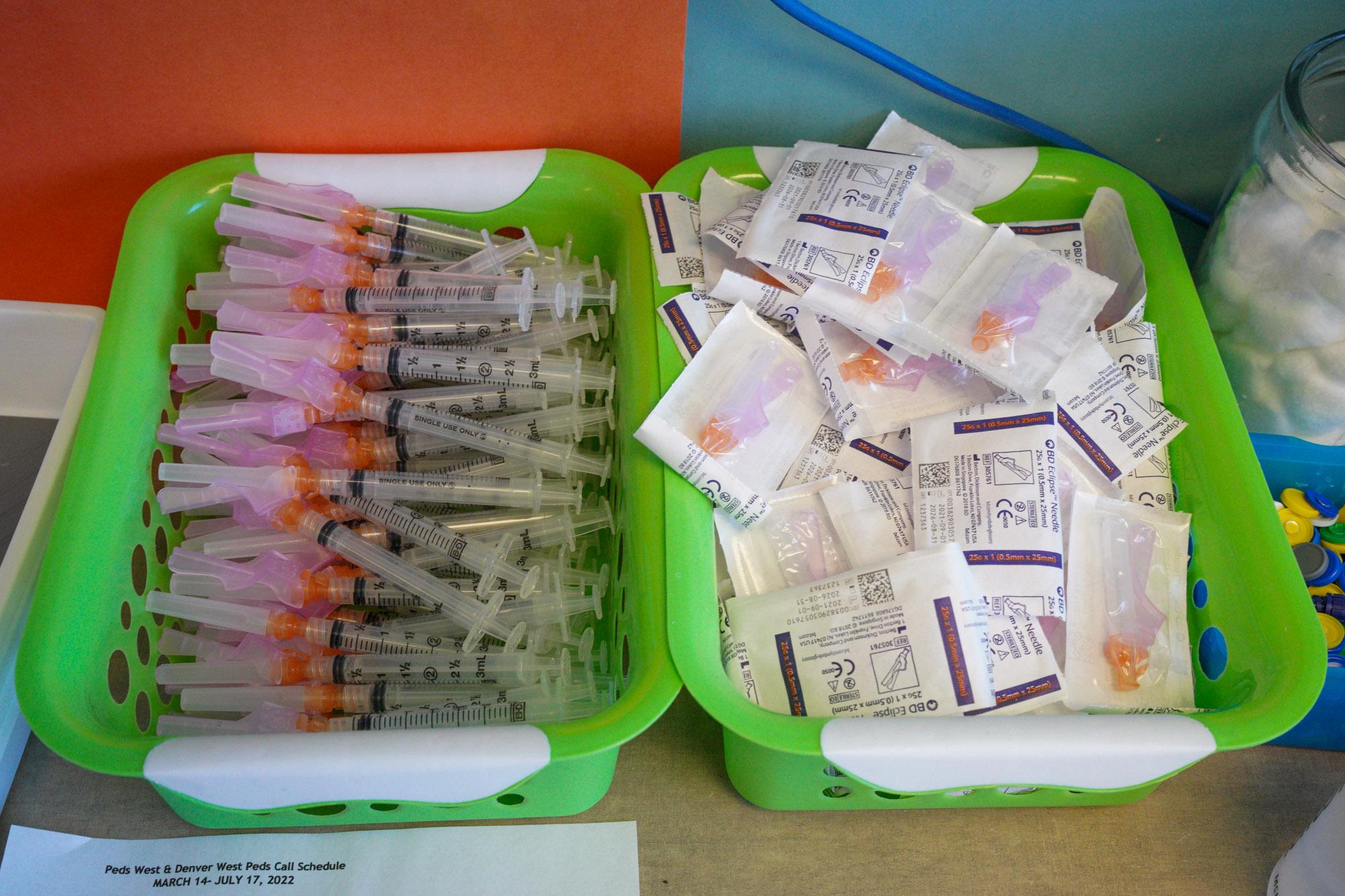

“It’s been a huge challenge,” said Dr. Sam Dominguez, who heads up testing at Children’s Hospital Colorado, the first hospital in the state to set up its own COVID-19 testing site.

He described the normal testing done in medical labs as complicated under the best of circumstances. But in the middle of a global pandemic, with high demand for supplies in countries and states worldwide, the struggle to ramp up COVID-19 testing has been daunting.

“Everyone needs the same things and there’s limited numbers,” Dominguez said.

He described the multi-step process to perform a test for the virus. The first step is a health care worker, in personal protective gear and a mask, taking a sample using a special swab from a patient. That swab, which looks like a large Q-tip, is long and bowed so it can extract a sample from the mucous membrane inside the nasal cavity. That sample is delivered to a lab, often in a few hours, nearly always by car.

Once there, the specimen gets processed by lab techs who extract the virus’s RNA, the genetic material which helps regulate the genome.

After that, lab workers test the sample.

“They are looking for the actual RNA, the nucleic acid of the virus in a clinical specimen,” Dominguez said.

The presence of that RNA allows them to say whether the new coronavirus is present. Each step of the process requires special reagents.

It’s a complicated process that uses a lot of supplies: personal protective equipment for workers, swabs, gloves for lab techs, reagents of different kinds, large expensive machines for the genetic testing, tubes. Some of those essential items have been in short, or less-than-reliable supply since the beginning, limiting how much testing can be done.

Dominguez described a high level of competition for the same supplies among hospitals and health departments around the country and beyond.

“You’re desperate on some level,” he said, much like the fierce jockeying for personal protective equipment that’s been seen in recent weeks. Some hospitals have gotten creative — for example, 3D printing swabs.

In some cases, Colorado’s labs have essentially ended up in bidding wars for scarce products.

“It was really like the Wild West out there,” said Scott Bookman, incident commander for the state’s public health department. “Whether it was around testing supplies or whether it was around ventilators, every area that we were bidding on equipment, we found ourselves competing against multiple, multiple other agencies.”

That included other states, as well as federal agencies like FEMA.

“Many times we didn't even really know who we were competing against. We just knew that we would make an offer and we'd get it or we wouldn't,” Bookman said.

Supplies are now in “unprecedented” demand globally, which is limiting supply for now.

“We have confidence in the ability of our manufacturing community to step up and to meet this demand over time,” Bookman said, noting more swabs, protective equipment and testing supplies like reagents could soon be available.

The testing situation in some other countries seems more robust. As NPR reported, Germany makes most of its “high-quality” test kits on a scale beyond most other countries, about 120,000 tests per day, for a population of 83 million. That’s helped limit the spread of the virus and the number of deaths.

The wheels are turning in the U.S. to further build testing capacity. Legislation in the works in Washington would provide a major infusion of $25 billion to expand COVID-19 testing.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first coronavirus test that lets someone gather a sample at home.

Hospitals and health care systems, which are doing much of the testing, say it’s slowly getting easier to get supplies.

“Over time that supply chain has opened up and now we have the capacity to do many more tests than we could initially,” said Dr. Tom MacKenzie, the chief quality officer at Denver Health.

The same is true at HealthOne/HCA, which includes several Denver area hospitals including Presbyterian, St. Luke’s, Swedish and Rose.

“I would say that really over the last month and especially over the last two weeks, vendors continue to produce those test kits, which we need in order to run the samples,” said Dr. Heather Signorelli, chief laboratory officer for HealthOne/HCA.

In March, Dwight Macero developed a mild sore throat. Two days later, the 35-year-old felt worse: chills and a fever. Soon, he got tested, first at an emergency room and then a drive-through testing site in Aurora. Roughly half a day later, he got news of a positive test result and began to self-quarantine.

The illness was rough for Macero, who was bed-ridden with a fever above 101 degrees for three or four days and severe aches. He contemplated his mortality and felt “a lot of anxiety.” Because he’s a health care worker, a physician assistant in bone marrow transplantation, Macero was able to get a test and now has recovered.

“I was very lucky,” he said. “We need more broad testing.”

Testing is growing, but slowly.

On Wednesday, Polis announced a shipment of tests, as well as shipments of supplies, are on their way to the state. He said 150,000 tests are expected to arrive by the end of the week. Another 150,000 swabs are expected to arrive in mid-May.

The state has also partnered with Colorado State University and Gary Community Investments, a B corporation based in Denver, to expand and deploy hundreds of thousands of tests.

Much of the ramping up of testing is happening at the hospital system level. Many of the biggest systems like Centura, UCHealth, HCA/HealthOne and SCL Health expanded testing in recent weeks.

Kaiser Permanente Colorado said it too had been ramping up testing and was now able to complete more than 1,000 tests a week and planning to expand testing in the coming weeks. Still, due to limited testing supplies, nationally only people with symptoms of COVID-19 who are identified as high-risk for severe disease, or as high-risk to transmit the disease to others, such as first responders, currently qualify for testing, the health system said in a statement.

Denver Health, the state’s main hospital that provides health care for individuals regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay, has tested about 4,000 people in the last 30 days. They can now do 400 tests a day.

Those tested include first responders, health care workers, hospitalized patients and symptomatic outpatients. It has three testing locations around the city and at its community health centers. These have been by appointment only with a doctor’s note.

“We don't do any walk-ups, but we've been able to gradually increase the volume of testing we're doing at those sites,” MacKenzie said.

Now, it’s actively reaching out to patients, ”so that we can get people into testing who may not call with concerns about their symptoms,” he said.

“We think there are probably a number of people who are staying at home with symptoms and don't really realize that they could have access to testing,” MacKenzie said.

He said Denver Health can send messages to 115,000 patients who are signed up through an electronic patient portal. The plan is to have them fill out a survey. If a patient has symptoms and needs a test, they’ll get scheduled for an appointment.

The hospital also plans to expand testing for two of the most vulnerable populations: those experiencing homelessness and those in nursing facilities.

“We think those are areas where we could see a rapid rise in cases if we don't identify them early,” he said.

The hospital is working with Colorado’s Coalition for the Homeless on a testing strategy.

“If they have symptoms, we want to make sure to identify them before we send the patient to a respite bed or to a shelter (to avoid inadvertently spreading the virus),” MacKenzie said. “They're a high priority population for us. We are also trying to figure out how you do regular surveillance of infections within the homeless shelters.”

He said the hospital already has relationships with a series of facilities that provide in-patient rehabilitation and medical treatment, often for the elderly, and is talking to them about doing testing.

“It's been a struggle for a lot of folks,” he said. “And they don't think that enough testing is being done.”

Antibody testing could also help fill the wide gap between supply and need right now. The test detects antibodies in the blood, which show if a person has had COVID-19 and developed an immune response to the virus that causes it. There are questions about their reliability still, but starting Friday, National Jewish Health, a hospital in Denver, will begin offering COVID-19 antibody testing, although tests are already sold out for the next week.

A month ago, Dr. Richard Zane, chief innovation officer at UCHealth, had an ominous warning. Now, he said Colorado seems to have navigated through at least the early part of the storm.

“I feel like we're in a good place, but a very tenuous place,” he said.

Coloradans took social distancing seriously and it accomplished what it aimed to: flatten the curve of cases.

“It just means that we're in a steady-state where we have more capacity to care for patients than there are very ill or sick COVID patients,” he said. “And that's really important. And as long as social distancing continues, I feel very confident that we'll get through this.”

Other public health researchers say testing may be able to catch up, given the increased and growing availability.

“I think it (testing) has significantly improved, and certainly from where we started to where we are now, it's like night and day,” said Dr. Michelle Barron, who specializes in infectious disease at UC Health.

Barron said more people who think they have symptoms are able to get tested and turnaround times, from swab to result, are getting better too.

But she also sounded a note of caution.

“I think in terms of where we need to be, I don't think we're quite where we want to be yet. I think we're getting better, but not quite there,” Barron said

She said ideally anyone who wants a test could get one.

“We're definitely not there at this moment.”