Newly minted college graduates have landed into one of the most difficult job markets in recent memory.

While the number of weekly unemployment claims in Colorado has declined since the mid-April peak, they’re still three times higher now than compared to the Great Recession.

Job offers have been rescinded or delayed by months. Students who need work may have to put themselves at risk, choosing work at grocery stores or gas stations.

“I think it’s going around social media that our generation’s first memories are 9/11, and now we’re all graduating into a job market that is virtually nonexistent,” said Colorado School of Mines civil engineering graduate Madelyn Caviness.

A planner by nature, Caviness considers herself one of the lucky ones.

She began driving around her freshman year in Denver to look for construction firms she might one day work for. After two summers interning for Swinerton commercial construction, Caviness secured a full-time job offer.

Since construction was deemed an essential industry during Colorado’s stay-at-home order, she knows her full-time work experience will require her to make new friends through a mask and virtual meetings.

“You lose that personal connection with people,” said Caviness, who chose construction because she wanted more social interaction compared to other engineering fields. “All of the sudden you’re reading people by the tone of their voice and their body movements rather than the shape of their face.”

No career field is completely untouched by the economic downturn, according to Edwin Koc, director of research, public policy, and legislative affairs at the National Association of Colleges and Employers. The nonprofit association does regular surveys of employers and was expecting a 6.5 percent increase in jobs for college grads in 2020 before the pandemic mucked up plans.

“This situation is extremely unusual in how rapidly the market has changed,” said Koc, who also worked at NACE through the 2008 Great Recession.

Perhaps the only silver lining is that NACE finds the majority of graduates who had already accepted job offers this spring are more likely to see their start dates delayed, not revoked.

“You may not be starting on time...you may be delayed, but you probably still have that offer in hand,” he said.

It’s a familiar-sounding story for University of Colorado Boulder grad Rebecca Litton, who earned a major in business management from the Leeds School of Business.

Litton interned last summer at the consulting firm Deloitte. She was excited to start her job and felt ready. Then she got the phone call.

Her start date was delayed until January 2021.

Deloitte will pay a small stipend to help defray some of the costs, but Litton now finds herself in a outbreak-fueled job limbo for six months.

“I want to do something meaningful, I would like to explore some of my other areas of passion,” said Litton, who is investigating volunteer opportunities and internships related to political science and foreign policy.

The bad news for college grads is that jobs like restaurant or hotel work aren’t something to fall back on due to public health closures. This was particularly crucial for students that dreamt of highly specific career paths that require building professional networks. Colorado State University graduate Tilo Lopez had hoped to translate his journalism major into a job being a cameraman for live sports.

“At first I was looking for a career back in February, and now I’m looking just to get a job to survive. So my standards are definitely lowered. I’m just looking for any place that’s hiring now,” said Lopez.

Tess Lieber majored in film production at CU-Boulder with a specialty in analog 16-millimeter film. It's a career path that depends on connections.

“There’s not much of an opportunity for networking right now. It’s mostly just email. You could shoot someone a call, they could probably answer their phone. But everyone’s in limbo. There’s no promises that can be made,” she said.

Koc calls the lack of transitional jobs “highly concerning” for grads because it could take students even longer to build professional networks that they don’t necessarily have right out of college. He advises students to not sit idle. While they’re looking for work, they can volunteer.

“It’s going to take a while to get a job. You may have to go outside of your preferred field and look broadly at the types of jobs available,” he said.

The worry is that the coming months could be especially trying on recent graduates who don’t have robust support networks, particularly first-generation grads and minority students.

“[Those students] will probably take longer, and could be even further behind in their career development. It will just increase a level of inequality that already exists,” Koc said.

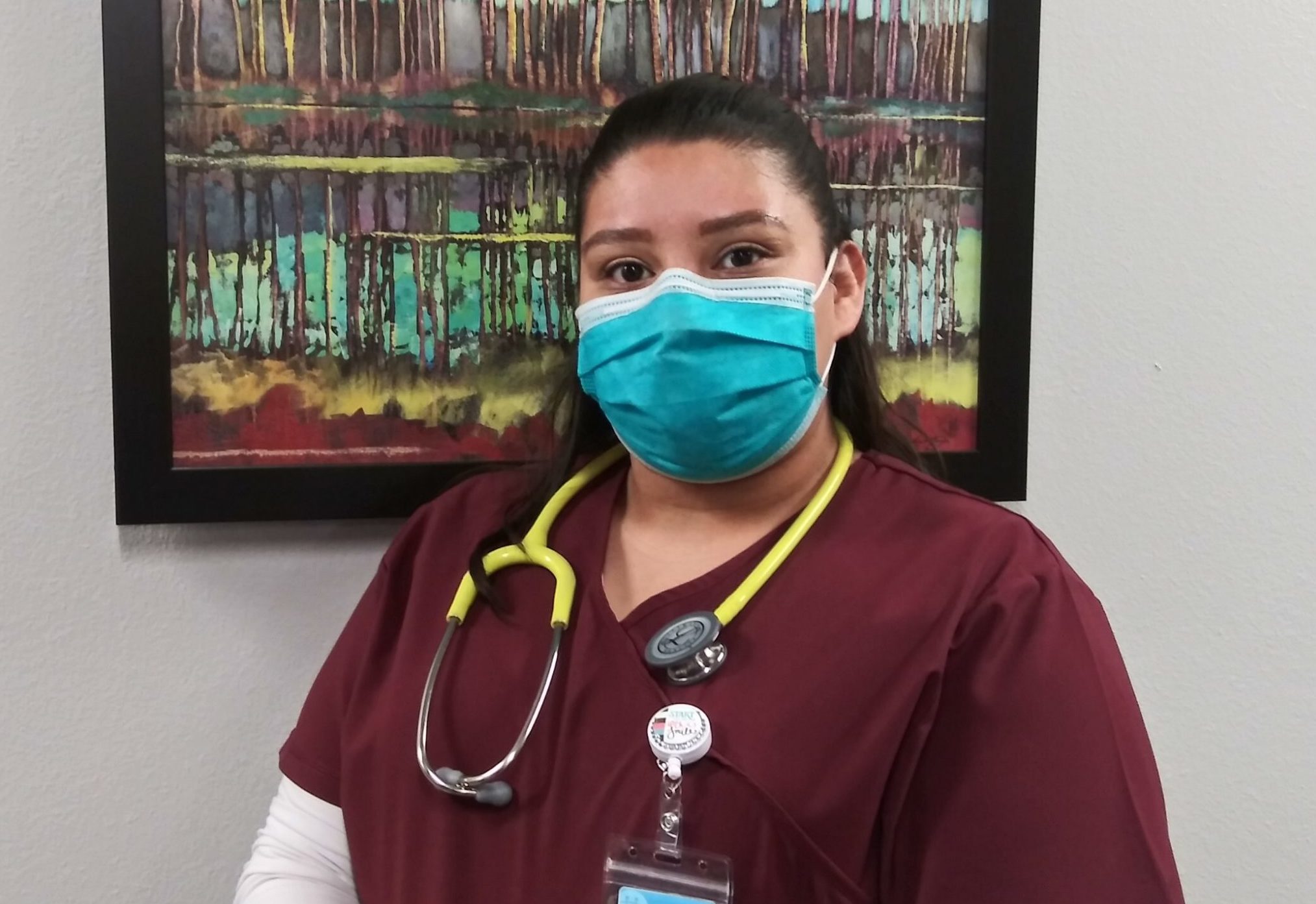

In those instances, finding the right mentors could make a big difference. Kelley Crespin, a first-generation student and recent grad from Front Range Community College, leaned on mentors in school and at her new job as a medical assistant.

“It definitely was scary at moments,” said Crespin as she reflected on the early days working as a medical assistant under COVID-19.

But Crespin pushed through and things became less scary.

“I’m just so happy to have been surrounded by the people I was because they really were the best mentors to get me through this time,” Crespin said.

Based on her experience, Crespin has another bit of advice. She said some in her workspace who had years of experience sometimes struggled with new COVID-19 medical protocols. She got used to them quickly because she didn’t know any different.

Sometimes a fresh perspective can make all the difference.