Chris Ciarallo paced his small hospital room while watching the news. He talked to his doctors over the phone, and only saw other people three times a day when they brought his food and medicine.

He tested positive for COVID-19 a week earlier on April 20. Before his diagnosis, Ciarallo was intubating COVID-19 patients at Denver Health where he’s the director of pediatric anesthesiology and staff anesthesiologist. He suspects he caught the virus while at work.

“The first week was at home fevers, bad night sweats, you know, changing clothes three or four times a night cause you're sweating and rigoring all through the night,” he said. “Some headaches into muscle aches. But again, nothing that I couldn't handle at home.”

What he thought would be a week of illness and then back to work, turned out to be a hospital stay.

His condition only got worse.

“I started coughing up pink fluid, dropped my oxygen, my heart rate wouldn't come down from about 120, 130,” he said. “I just couldn't get the fever to break.”

He and his wife, who’s also a physician, consulted their friends and colleagues who insisted Ciarallo go to the hospital. His wife taped off the back of the minivan so they could stay separated. They each wore N-95 masks as she drove him to the ER at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital.

“The hardest part of that is driving up to the front of the hospital and saying goodbye from a distance. Saying, you know, ‘I'm sure I'll be okay, but maybe not.’ No hugs, no nothing. Just kind of dropped off like an ambulance would and then she disappeared,” he said. “Walking into the ER, knowing that I'm exposing other people, not knowing what my trajectory is and went into the hospital hoping for some answers.”

At the hospital, his labs were declining, but he wasn’t bad enough to need a ventilator. Ciarallo was also too far out from his COVID-19 diagnosis to partake in the hospital’s trial of an antiviral drug, Remdesivir.

“Nothing more disheartening than coming to a hospital to get blood thinners and Tylenol and being told that there's really no other options for you,” he said.

With no proven treatments for COVID-19, his doctors could only do so much. But, Ciarallo knew that doctors at the hospital were using plasma to treat patients with the virus.

“No one really had a plan for a 43-year-old that didn't need to be on a ventilator, whose labs just continued to get worse,” he said. “So, that was when I pushed the infectious disease doctor to take a look at convalescent plasma, because I really didn't have any other options available to me, but I was physically and laboratory wise continuing to get sicker.”

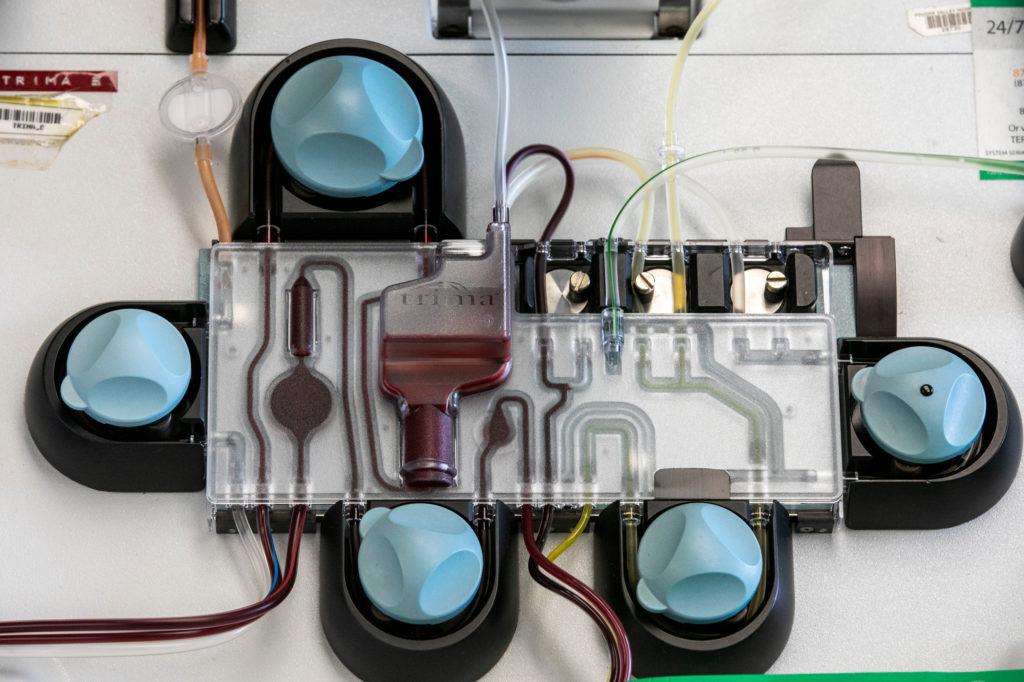

Just a few weeks prior, the Food and Drug Administration had made it easier for doctors to use convalescent plasma on COVID-19 patients. Plasma is the liquid, antibody-rich part of blood. It’s used all the time to treat people with immunodeficiencies, clotting disorders and burn or surgical patients.

The idea is that the antibodies contained in the plasma of someone who has recovered from COVID-19 will help patients who are sick with the virus.

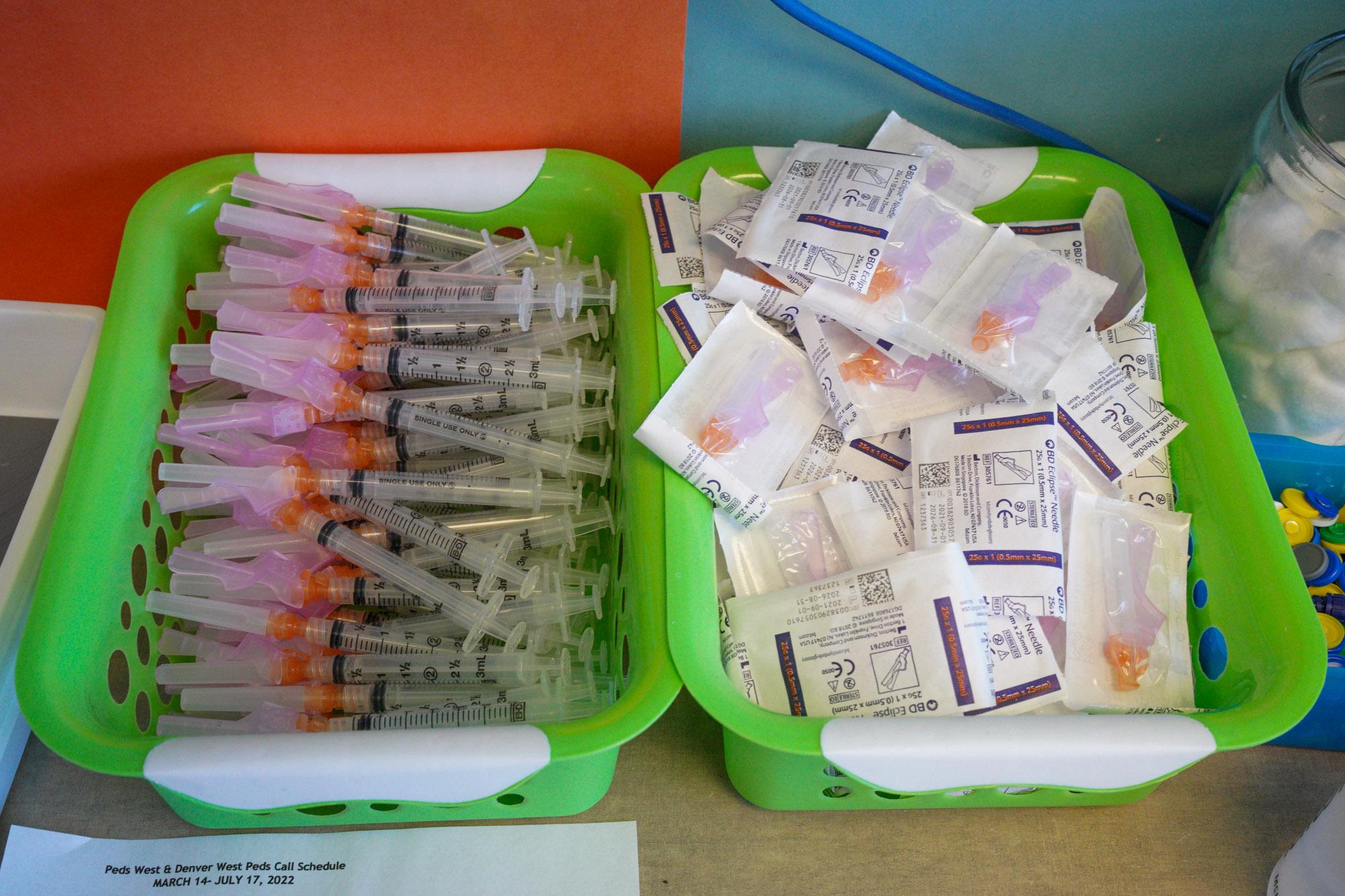

In late March, Dr. Kyle Annen, medical director of the blood collection center at Children’s Hospital Colorado, collected the first COVID-19 plasma donation in the state. She worked quickly to get it to a patient at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital.

“We really just were able to put a rush on things when we felt that they were a priority. And this convalescent plasma collection was an example of that,” Annen said. “My team was just all hands on deck ready to go. Everyone recognized how significant this was and how important this was for this patient.”

At the same time, Dr. John Eisenach at Kaiser Permanente was working to get hospitals, researchers and blood banks together to create a statewide coalition.

“The United States leads the world in the number of cases of COVID-19 and the number of deaths: truly tragic and humbling statistics,” he said in an email. “However, we can also lead the world in the fight against both current and future viral pandemics by scientifically proving the success of a therapeutic strategy that is most immediately available after the introduction of a novel virus.”

The Colorado COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project Consortium was born. It includes Children’s Hospital Colorado, Colorado State University, Denver Health Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Colorado Region, National Jewish Health, SCL Health, UCHealth, the University of Colorado Anschutz Campus, and the Vitalant Blood Center and Research Institute.

To meet the needs of hundreds of sick patients in Colorado, someone needed to collect hundreds of units of plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients and disburse those units to hospitals across the state — collaboration was vital to scale up collection and meet the demand.

At Vitalant, one of the nation's oldest and largest nonprofit blood service providers, Larry Dumont, director at the Vitalant Research Institute in Denver, and his team worked tirelessly to scale up collection of COVID-19 plasma.

“So number one, it does appear safe, number two, there are remarkable anecdotal reports of the likely effect of this plasma on patients,” Dumont said. “And of course there's other anecdotes where it appears there was no effect. So that's why I'm optimistic, but we've really got to have well-designed clinical trials.”

Convalescent plasma has been used since the 1890s, and there’s evidence it was used to treat those with the 1918 Spanish Flu. More recently, it was used in SARS and Ebola patients with some effectiveness. But testing plasma for COVID-19 patients began recently, and there are still a lot of questions to be answered.

“Well, what kind of unit did they receive? What were the antibody levels? Were their neutralizing antibodies against the virus in those units? You know, all sorts of questions come up about what makes a good unit or a not good unit. How well do we match it to a patient?” said Dr. Rebecca Boxer, the director for clinical trials at the Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Research. “A patient who's very sick, are they going to respond to convalescent plasma the same way as a patient who's not yet that sick?”

There may be a time in the illness when the plasma has the most benefit for a patient. When the FDA expanded access to plasma and released guidance, they advised doctors use plasma in patients with ”serious or immediately life-threatening COVID-19 infections."

Ciarallo didn’t quite fit the definition, but he was approved to receive the treatment anyways. Another man, Scott Kaplan, received plasma after he was ventilated. He showed some signs of improvement, but ultimately died.

Dr. David Beckham at University of Colorado Hospital has started a clinical trial that compares patients treated with plasma to a database of patients who did not receive the plasma nor participated in other clinical trials. So far, he and his team have enrolled 82 patients.

“My hope is that we'll get some information and data from this and it'll help lead to more targeted therapeutic approaches and preventative approaches in the future,” Beckham said.

Nationwide, more than 16,000 patients have been treated with plasma at hundreds of hospitals. The FDA created a national program with the Mayo Clinic and the American Red Cross, and funding from the federal government's Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. The Project launched a website for patients, healthcare providers and potential donors.

In Colorado, nearly 1,000 people have been treated. The Consortium was the first regional collaboration of its kind in the U.S. and the first to collect and deliver COVID-19 convalescent plasma to critically ill patients, according to the Consortium.

While Vitalant and hospitals have been able to recruit donors and collect enough plasma to treat patients in Colorado and even send some units to other states in need, Dumont is planning for a second wave of the pandemic, which could be worse than the first.

“On my worry list, as I shift from one list to another, is really what's going on in the fall and the winter,” Dumont said. “Because if things get really rough even though we're collecting a lot of plasma, are we going to have enough to be able to, to support people? Cause I don't want to see us back in a February, March situation. It would be a shame.”

Twelve hours after Ciarallo requested the treatment, he was sitting in a chair watching more news on the TV as the plasma was pumped into his arm.

“Within about two hours, I noticed that I wasn't warm anymore,” he said. “My heart wasn't beating out of my chest, within two hours I had an appetite. I got up, went to the bathroom, I stopped coughing up pink frothy stuff.”

The next day, he was up and moving around easier than he had before. His colleagues brought him Chick-fil-A for lunch, and then his doctors told him it was time to go home.

“So I packed up my stuff, called my wife,” he said. “The most amazing thing was I physically walked to the elevator and walked downstairs and walked out the front door of a hospital and sat there on a bench and waited for my wife.”

Ciarallo tried to donate plasma to help patients like himself, but he can’t donate for one year after receiving a transfusion. In the meantime, he’ll continue to do his part by taking care of patients and remembering what it was like for him.

Results from clinical trials investigating convalescent plasma across the country will be published over the coming weeks and months. Until then, doctors in Colorado plan to continue treating COVID-19 patients while waiting for other drugs or vaccines to be developed.